In Sao Paolo, a major forum to consider the biennial ‘from the point of view of the southern hemisphere’. The main focus is on Dakar, Istanbul, Jakarta and São Paulo. But where is Sydney? South, but not Global South.

In Sao Paolo, a major forum to consider the biennial ‘from the point of view of the southern hemisphere’. The main focus is on Dakar, Istanbul, Jakarta and São Paulo. But where is Sydney? South, but not Global South.

Kay Abude, Piecework, 2014 Steel, MDF, timber, plywood, fluorescent lights, chairs, cardboard, paper, plaster, silicone rubber, paint, brushes, various modeling tools and steel utensils, latex gloves, cotton and nylon rags, cotton velvet, silk, rayon braided cord and workers. Dimensions variable

Piecework, 2014 is an installation and series of durational performances that occur throughout its exhibition in Gallery 2 at Linden Centre for Contemporary Arts. The installation consists of three workstations and three workers dressed in a uniform. The workers engage in an activity of casting plaster objects from moulds in the form of 14.4kg gold bars. These casts are then painted gold. Piecework displays a purposefully futile labour of a repetitive and tireless fashion. It explores a form of work relating directly to performance that is quantifiable, investigating ideas of power and value and asks questions about the role and meaning of labour within artistic practice.

Shift work is characteristic of the manufacturing industry, and the artwork employs performative strategies in a rigorous process and task orientated manner by using Linden as a workplace that is in constant operation over the period of a 24-hour cycle. The ‘three-shift system’ is performed (Shift 1: 06:00-14:00, Shift 2:14:00-22:00 and Shift 3: 22:00-06:00) by the three workers who produce these gold bars throughout the six week exhibition period. The workers are paid a fixed piece rate for each unit produced/each operational step completed per shift. Ideas of the factory are embedded in the vary nature of the work mimicking a manufacturing process carried out by uniformed workers who take up their posts in eight hour shifts.

The catalogue essay by Jessica O’Brien:

The poetry and politics of production

Addressing the intersection between art, life and capitalism, Kay Abude’s Piecework interweaves personal experience, a critique on the distribution of global economic power, and the relationship between producers and consumers.

Piecework unfolds over a six-week period. A durational performance piece highlighting labour and process, the performers undertake manufacturing processes that reference the artist’s personal experience and recent site visits to Chinese factories. The group works through an endless pattern of standardised procedures that result in gold painted serialized plaster ingots. The performances are structured according to a three-shift system, dividing the day into three eight-hour working shifts that mimic a continuous 24-hour production cycle.

By foregrounding the body of the worker, Piecework engages with the pervasive neo-colonial first world practice of exploiting emerging economies and their abundance of cheap, unregulated labour. With most of Australia’s goods produced offshore, the performance addresses the disconnection in the minds of the consumer between the products we buy, and the often dehumanising labour that is required to produce it.

Banal, repetitive, precise and designed for maximum efficiency, Piecework could stand in for the processes behind countless products and could be extrapolated in factories a hundred or a thousand times over. Each action is carefully considered, creating a Haiku-like poetry to the work.

Highlighting the formality existing in standardised production, there is a purposeful ambiguity in the artist’s aestheticised interpretation of reality. Kay writes: “Two different types of labour exist in the two environments of the factory and the studio. The large populations filling the factories are dependent on the market that exploits them. These people labour because they must work for their livelihoods – they work in order to live and survive. The labour present in art practice is one that is voluntary and pleasurable for the artist – the artist lives to work and create.”[1]

Downplaying the desire for a single ‘artist’s hand’ in the work, while expressly displaying the labour that it took to create it, the audience is left to question the value of the objects that are produced, and how it is conferred.

At the crux of these ambiguities is the role of the audience in the artwork. “The fine arts traditionally demand for their appreciation physically passive observers…but active art requires that creation and realization, artwork and appreciator, artwork and life be inseparable.”[2] Utilising the understanding that the relationship between the artist and the audience is at the heart of Performance Art, the seemingly passive and non-participatory viewers of Piecework are in fact directly implicated in the work.

Piecework replicates the role the audience plays as participants of consumer culture, in their role as consumers of the artwork. Abude is the manufacturer and we the consumer. Without a market or an audience, ‘production’, in every sense of the word, would not exist.

By foregrounding the human process by which consumer goods are made through the physical presence of the workers, Piecework addresses the disconnection and compartmentalisation that is characteristic of present day consumption in a capitalistic society. And yet it also replicates those very relationships, distilling and aestheticising disturbing imbalances of power.

As Claire Bishop’s remarks: “The most striking projects… [hold] artistic and social critiques in tension.”[3] Piecework is a considered response to a pervasive social issue, but does not attempt to present a fixed meaning, or take on the herculean responsibility of suggesting a solution to global economic inequality. As unwitting participants of the performance, the significance we chose to ascribe to our role as a consumer of product and artwork is up to us.

Jessica O’Brien

June 2014

Jessica O’Brien is an independent curator and writer based in Melbourne.

[1] Abude, Kay, Put to work, M Fine Art, Faculty of the Victorian College of the Arts and Music, The University of Melbourne: November 2010, p. 28.

[2] Kaprow, Allen, Essays in the Blurring of Art and Life, Berkeley: University of California Press: 2003, p. 64.

[3]Bishop, Claire, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, Verso Books: 2012, p. 277-8.

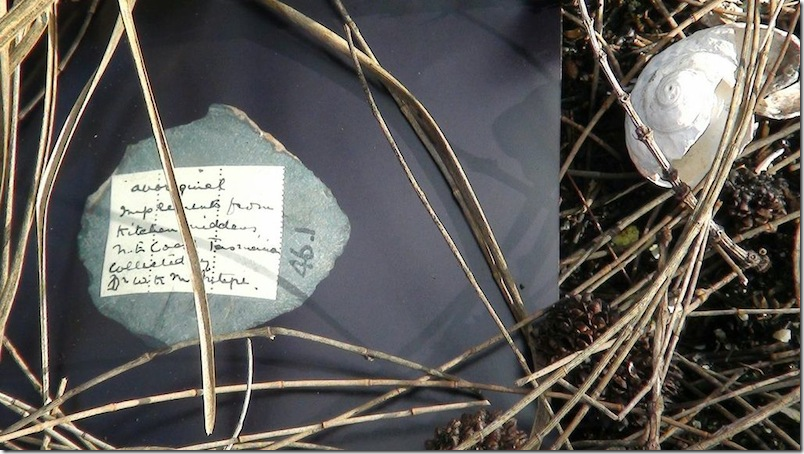

Julie Gough, The Lost World (part 2), 2013, installation detail. Photo courtesy the artist

South is an important identity for Tasmania. At the bottom of the world, it offers a space for alternative activities that slip below the radar, that might otherwise not be possible in the metropolis. On the other hand, however, it has become a marketing term with romantic associations useful for selling gourmet food and tourist experiences. It was said: ‘Underlying this is a murmur in the back of our minds about a paradise lost that can be regained.’ There is potential to engage with other Souths. Singapore, for instance, has a complex relationship to the North. In such centres, one can feel that one should replicate models located in the North in order to develop. This creates a counter argument for the importance of local referents. The roundtable revisited a proposal that Greg Lehman and Jim Everett developed as part of the South 1 event in 2004. The idea for the Museum of Southern Memory emerged originally as a response to the work of Marcelo Brodsky in Argentina, who documented the memories kept alive of those who were disappeared during the military dictatorship in the 1980s. There seemed an important role for an institution that could house those memories which need to be kept alive. It was said, ‘Tasmania is part of the geo-political South of Australia. One aspect is that after the colonial tsunami has washed over and retreated, it wipes away native cultures and people.’ The proposed museum would share Tasmania’s experience of loss and recovery with other parts of the South. It could be a museum towards which any visitor might feel they could make a contribution. As well as including stories of victims, there is potential to also include non-literate techniques for memorialisation, such as knotting. This was highly developed in the practice of quipu as a form of record keeping in Inca Peru. In general, the table agreed on the importance of maintaining multiple perspectives. The binary identity of indigenous and non-indigenous did not reflect the way in which we are all products of a colonial mindset and we all have a potential relation to place. The group will continue to work on the idea of a Museum of Southern Memory, eventually with input from other voices in the South. Present:

Julie Gough The Lost World (part 2), 2013 Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, and CAT (Contemporary Art Tasmania) (Solo exhibition) Curated by Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll Design by Christoph Balzar Technical design by Ronald Haynes and Mark Sheppard +23 October – +30 November 2013 Project URL: CAT (Contemporary Art Tasmania), http://www.contemporaryarttasmania.org/program/the-lost-world-part-2 Project URL: Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge http://maa.cam.ac.uk/maa/the-lost-world-part-2/

“Passion for the land where one lives is the foundation of belonging and is an action we must endlessly risk.” Eduoard Glissant

Previous roundtables explored strategies for countering the commodification of art through the practices of the gift and openness. The Sydney roundtable brought together artists and writers who have an interest in local context. In a peripheral country such as Australia, the international stage beckons as a recognition of worthiness. The goal was to propose how the local might be represented without seeming parochial.

It was the evening of Bloomsday, an international celebration of locality in space and time, marking the day’s journey through Dublin. The discussion was located in Addison Road Centre, a long-established precinct for cultural activity in the inner-western suburb of Marrickville. The various tenants there, representing diverse ethnic backgrounds and scavenging economies, reflect an local resilience.

The participants focused particularly on the understanding of place as a key goal. One aspect involves knowledge of local plants, particularly their names and how they might be used in cooking and/or medicine. The process of gathering this knowledge draws on the different cultures that inhabit this place, which have alternative ways of using what can be found. Underpinning this is a belief that paradise is here on earth.

A number of shared opinions underpinned this focus on place.

Post-colonial guilt is no longer useful. It has the effect of alienating us from place. Respectful acknowledgement of traditional ownership should not stop us embracing our responsibility for looking after our part of the world.

An important means of gaining local knowledge is walking. Walking not only helps us discover the local, it connects disparate elements together through experience. Walking need not only be an individual action, it can also include collective actions such as parades and marches.

The challenge emerges of how to locate this local. Within the concentric context of the ‘international’, the local is inferior. The local is less advanced and less informed than the metropolitan centre.

Within the perspective of Southern Theory, the local acknowledges its dependence on context, whereas the metropolitan centre presumes a universalism that denies its own locality.

One proposal to explore this perspective is to find a way of linking localities together that is not hierarchical. Working at the level of council, there is potential to activate connections between suburbs similar to Marrickville in Sydney, such as Brunswick in Melbourne and Tlalpan in Mexico. Similar processes of place-making such as foraging should be undertaken in different geographically distant localities. The results could then be shared. The common experience offers a sense of solidarity to counterbalance the centripetal pull of the metropolis.

There is potential to formalise this into an event like a locally distributed biennale. This would involve identifying a specific time period in which events would occur and be shared between different places. Alternatively, it may be possible to consider connections based on contrast, such as the different political orientations of Sydney’s Marrickville and North Shore.

Questions which arise from this idea include:

The idea of a rhizomic biennale is now open for future development.

Participants:

Therese Keogh was invited to create work for the Sievers Project, an exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Photography that revisited the work of a major Australian photographer who documented the glories of industry in the 20th century. Keogh was drawn to Sievers’ photograph of a severed hand holding a sheaf of wheat, a fragment of the marble statue of Ceres in Rome. She discovered that much of the imperial marble was eventually transformed into quicklime used to make concrete. It can also be used as a soil amendment to counterbalance soil acidity. In order to investigate this process herself, Keogh sourced a marble pediment of an altar from a church in Ballarat. She then worked out how to fire this marble, which was eventually displayed in the gallery as a block of quicklime.

Therese Keogh was invited to create work for the Sievers Project, an exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Photography that revisited the work of a major Australian photographer who documented the glories of industry in the 20th century. Keogh was drawn to Sievers’ photograph of a severed hand holding a sheaf of wheat, a fragment of the marble statue of Ceres in Rome. She discovered that much of the imperial marble was eventually transformed into quicklime used to make concrete. It can also be used as a soil amendment to counterbalance soil acidity. In order to investigate this process herself, Keogh sourced a marble pediment of an altar from a church in Ballarat. She then worked out how to fire this marble, which was eventually displayed in the gallery as a block of quicklime.

Keogh’s work witnesses the reduction of art into commerce. This can be seen as a loss echoing the demise of the grand paternalistic world of manufacture once celebrated by Sievers. But it can also be seen as a recovery of value from what is left behind, returning products of human endeavour to the earth from whence it came.

What is interesting from the perspective of South Ways is the adventure of the artist in confronting the material challenge herself, without recourse to external assistance. Her two hands thus provide a tangible link between the various phases of the cycle, moving from monument to earth. They allow us to witness the transformation of matter itself, a dimension otherwise absent from the silvery surfaces of Sievers’ prints.

Below are photos of the firing of the marble with Keogh’s description of the process:

These images show the firing of a marble object inside a large steel box. I started with a block of marble in my studio, and – over a period of several months – chipped away at its surface. I didn’t begin this process with an end point in mind. Part of me was looking for a fault in the marble, and so I kept carving in the hope that the stone would reveal its weaknesses, which would then allow me to stop. But one day the mallet I had been using broke with the force and repetition of the carving. The mallet’s head split in two, and it was like the marble was reacting against its own transformation. So I stopped.

Marble is a form of calcium carbonate, metamorphosed from limestone. When fired, the carbon dioxide trapped inside is burned away, transforming the calcium carbonate into calcium oxide, or quicklime. Quicklime doesn’t occur without human intervention, and is used for a variety of applications (including as a base ingredient in concrete, and, in agriculture, as a soil amendment to neutralise earth with high acidity). It is called quicklime (from the original meaning of the word ‘quick’ as something that is alive, or living) because when it comes into contact with water a chemical reaction takes place that creates extremely high temperatures, and has been known to cause severe burns to the skin of people working with it.

Once the carving had finished, I constructed a steel box that would house the marble during its firing. The box protected the marble from the smoke of the fire, and allowed it to be heated more evenly.

My mum owns a property in Central Victoria, where I took the marble and the box to be fired. I propped up the box, with the marble inside, on four bricks in a paddock, and built a fire around it. The fire burned for about eighteen hours, as I stoked it through the night. When it had died down, I took the lid off the box. The marble – now quicklime – had cracked as it heated and cooled. Its surface had changed from being luminous to kind of chalky, as its chemical composition was irreversibly altered from the fire.

Therese Keogh, After Firing (CaO), image courtesy Christian Capurro, 2014

Therese Keogh is a Melbourne artist – www.theresekeogh.com. Featured image at the top of this page is her hand-drawn version of the original Sievers’ photo.