At the opening of the series, Raewyn Connell laid down the challenge to broaden our theoretical references beyond the metropolitan centres. In the discussion that followed, there was a sense of concern in abandoning the reassuring authorities, particularly European theoretical figures. Would this be to forgo critical thought – to drift away from the main action in transatlantic universities? Connell countered with a democratic image of a thousand boats that would criss-cross the south-south axis.

Gibson and Birch pointed in an alternative direction. They both looked back to iconic figures in the early history of European colonisation. Gibson considered the life of William Dawes, a scientist who explored different ways of engaging with Indigenous hosts in Port Jackson at the time of the First Fleet. And Birch looked from the Victorian end at the biography of William Barak, a Wurundjeri leader who traversed the Indigenous and settler worlds. While Dawes and Barak would not be considered theoretical sources, their actions in their time provided models for ways of thinking today.

Gibson looked at Dawes’ attempts to understand the local language. His notebooks reveal that he moved away from a nominalist approach to an increasingly contextualised grasp of their language. This is in part thanks to his intimacy with a local woman, Patyegarang, who helped him appreciate the profoundly relational nature of Indigenous language. Gibson talked about Dawes as a ‘littoral’ person, a marine adept at working in the space between land and sea. His notebooks show a man navigating a shifting world, ‘always in conversation with oneself and other people.’

For Birch, Barak also negotiated between the white man (namatje) and Wurundjeri. Rather than a passive figure, Barak was always navigating a path as a political strategist. An important component of that was his relationship to the first manager of the Aboriginal mission in Coranderrk, John Green. Birch could see echoes here of his own collaborations with namatje such as the artist Tom Nicholson.

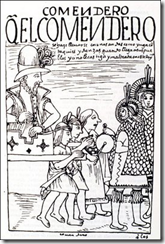

Other Australian writers have also recently depicted the first encounters between white and black worlds, such as Inge Clendenin and Kate Grenville. But it is not only in Australia that this interest has emerged. The Argentinean writer Walter Mignolo has written about the Inca historian Guaman Poma, who tried to tell his people’s side of the story in a book The First New Chronicle and Good Government (1615). Poma tried to identify how the best of European and Inca cultures might be combined. In doing this, he used a map dividing the world into four quarters, rich and poor, moral and barbaric.

In modern terminology, civilization and barbarism distinguished the inhabitants or the two upper quarters; while riches and poverty characterized the people living in the lower quarters. On the other hand, the poor but virtuous and the civilized are opposed to the rich and the barbarians. In a world divided in four parts, subdivided in two, binary oppositions arc replaced by a combinatorial game that organizes the cosmos and the society.

Walter Mignolo The Darker Side Of The Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality, And Colonization Anne Arbor: University of Michegan Press, 2003, p. 252

The next step would be to gather together scenes of first encounter as they are currently being rehearsed across the South. In these tentative experiences of contact, there is sometimes a brief flicker of dialogue before the full force of colonisation is finally applied. A glimpse of these proto-colonial scenes can speak to those countries where the tide of colonisation is now ebbing in the other direction.