IV ENCUENTRO SUDAMERICANO EN GESTION CULTURAL.

A gathering of South American cultural researchers in Valparaiso, Chile 9-11 October.

IV ENCUENTRO SUDAMERICANO EN GESTION CULTURAL.

A gathering of South American cultural researchers in Valparaiso, Chile 9-11 October.

Southern dialogues are developing strongly at this moment in time, though only to highlight the significant challenges ahead.

Southern dialogues are developing strongly at this moment in time, though only to highlight the significant challenges ahead.

The colloquium Diálogo Trans-Pacífico y Sur-Sur: Perspectivas Alternativas a la Cultura y Pensamiento Eurocéntrico y Noroccidental took place on 8-9 January, as part of the grand scale Congreso Interdisciplinario at University of Santiago, Chile. Latin America has been the home of particularly active southern thinking, inspired often by its indigenous cultures. The ‘south’ as a rallying call has been significant given the tangible counter-influence of the United States, to the immediate north.

The Santiago colloquium witnessed a change away from this previously combative north-south argument. The principal perspectives were from Chile, México and Argentina. Much discussion was given to the emerging relations with Asia, specifically China. Alongside this was the growing influence of Brazil across Latin America, reflected in the large number present for the parent congress. In the past, these south-south relations would have been flavoured by a solidarity against USA as the common hegemon. But now there is increasing recognition of a diversity of interests across the south, and the need to reflect this in a conversation which is not reduced to catching up with the North.

One tangible contribution of the colloquium was the title. The word ‘noroccidental’ literally means ‘north-western’. This refers more generally to Western culture in the North, rather than the top left corner of the globe. Such a term accepts that there is a Western culture in the South as well, particularly in countries like South Africa, Australia and Chile. But it differentiates itself from other northern countries, such as Russia and China.

Other emerging terms are ‘Euro-American’ and ‘trans-Atlantic’. The problem with these is that it uses the generic term to represent only one half—North America. ‘Euro-American’ does not include Latin America, nor does ‘trans-Atlantic’ feature exchanges with Africa. The challenge is to find an English equivalent of ‘noroccidental’. Would ‘north-Occidental’ do?

The plenary concluded with a call for a more global understanding of South, reflecting such developments as population flows through the North and the relational identity of North and South.

The challenge is to extend this dialogue beyond Latin America to engage with forums elsewhere in the South. There is much activity in South Africa at the moment around the book by Jean & John L. Comaroff, Theory from the South: Or, how Euro-America is Evolving Toward Africa, including the recent critical responses in Johannesburg Salon. In Australia, there is continuing reference to Raewyn Connell’s Southern Theory, as well as Indigenous Studies broadly taking on global themes.

The relative lack of connection between these dialogues is, of course, reflective of the condition of the South itself, as a series of spokes connected with each other only via a central hub in the North. Language is an added challenge. The convenor of the Congreso Interdisciplinario Eduardo Devés has developed his own perspective on the Southern condition through ‘periphery theory’, outlined in his publication Pensamiento Periférico, which is freely available in Spanish. The potential reduction of South to the condition of periphery is an important challenge to the broader historical narratives that it carries. To what extent the issues normally identified with South be characterised by the condition of distance from the centre? Such a perspective puts the historical conditions such as settler-colonialism into question.

Though the distances between the southern countries themselves should be identical to those separating northern countries, the ‘hub & spokes’ model works in a very practical way to mitigate against south-south travel. Many academics from outside Chile had to cancel their involvement in the colloquium due to higher than expected air fares. This is obviously compounded by smaller travel budgets for academic staff in southern universities.

Nevertheless, the University of Santiago is taking a lead in fostering south-south dialogue. In late October 2013, they will initiate an annual forum/workshop to ‘go full circle’ on the Pacific, looking at how a trans-Pacific exchange might be configured to include Latin America. The Asia Pacific is usually conceived as a domain exclusive to Australasia, East Asia and North America. But as with the APEC forum, the south-east arc of Latin America should be an integral part of that. ‘Full circle’ provides a focus on the Pacific as a space for multilateral relations. What would be the intellectual underpinning of this?

The time seems ripe for a major conference on these various strands of southern thinking. Given its position, hosting an international conference would seem one tangible contribution that Australia could make to this emerging paradigm. Alternatively, if it were to be held in a northern university, this paradox of having to go North to talk about South would provide sufficient material for a conference in itself.

One question that tangibly brings the condition of southern thinking home concerns the north-south asymmetry of the academic world. In particular, if someone had the prospect of an academic position in Europe or North America, would there be any value in remaining in a less well-endowed southern university?

Meanwhile, while waiting for such an event to emerge, four Australian academics have generous offered a summary of their work accompanied by a generative question:

As the Zapatistas would say, inspired by Mayan mythology, ‘walking we ask questions’. Thankfully, the path stretches out ahead.

The symposium South-South Dialogue: Alternative Perspectives to Western Culture and Thought will be held as part of the Third International Congress Sciences, Technologies and Cultures: A Dialogue Among The Disciplines of Knowledge, 7-10 January 2013, at University of Santiago of Chile (Usach). For more information, see link: www.internacionaldelconocimiento.org.

The symposium South-South Dialogue: Alternative Perspectives to Western Culture and Thought will be held as part of the Third International Congress Sciences, Technologies and Cultures: A Dialogue Among The Disciplines of Knowledge, 7-10 January 2013, at University of Santiago of Chile (Usach). For more information, see link: www.internacionaldelconocimiento.org.

In recent years, perspectives have emerged that contest the universal status of Western knowledge. Post-colonial thinking has recently been joined by new alternative paradigms, including Peripheral Thought, Southern Theory, Indigenous Studies and Decolonialism. Each posits the possibility of a knowledge that is particular to the South. This provides a basis for a south-south dialogue about alternatives or critiques of Western knowledge, involving researchers and intellectuals from non-Western regions (Latin America, Oceania, Africa and Asia).

Common questions emerge:

This symposium welcomes contributions to the evolution of critical approaches to Western thought. This includes reflections on colonisation, independence movements, notion of ‘Third World’ and ‘Developing Countries’, ‘Global South’ and neo-liberalism. As well as critiques of the West, this symposium aims to foster constructive alternatives that reflect the values of participating countries.

The abstract must be sent to e-mails of coordinators with following specifications:

The paper must be sent to coordinators´ e-mails with following specifications:

Please note the upcoming Symposium that SURCLA is organising: Indigenous Knowledges in Latin America and Australia | Locating Epistemologies, Difference and Dissent | December 8-10, 2011.

Please note the upcoming Symposium that SURCLA is organising: Indigenous Knowledges in Latin America and Australia | Locating Epistemologies, Difference and Dissent | December 8-10, 2011.

The symposium will bring together Indigenous educators and intellectuals from Mexico, Argentina and Chile to Sydney to meet with interested Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander educators, scholars and activists, as well as non-Indigenous practitioners and allies, to discuss different models and approaches of Indigenous Knowledges and Education in the tertiary sector and beyond.

This project aims at helping educators and researchers in the Higher Education sector of Australia and Latin America to identify opportunities for integrating in their research and teaching and learning relevant aspects of Indigenous Knowledges in the areas of culture, education and sustainability.

Apart from the symposium itself, academic publications, public lectures by distinguished visitors and the creation of a website, the project will stimulate debate on Indigenous Knowledge and film production in Latin America and Australia by hosting film screenings on the topic.

For more information, visit the website.

Convocatoria Estudiantes de Graduaçao, Pregrado, No-Graduados para III Congreso Ciencias, Tecnologías y Culturas

La Internacional del Conocimiento desea abrirse a la participación de la mayor cantidad posible de estudiantes de diversas disciplinas y países. Para ello ha establecido un conjunto de iniciativas. Se trata de promover entre estudiantes de grado-graduaçao la realización de un importante Viaje Intelectual a Santiago de Chile y a otras ciudades cercanas.

El congreso Ciencias, Tecnologías y Culturas se desarrollará en la Universidad de Santiago de Chile, 7-10 de enero-janeiro 2013

Simposios para jóvenes investigador@s

Habrá simposios especiales para estudiantes de graduaçao, sobre los temas:

Presentación de trabajos

Los resúmenes (15 líneas, título, autor@, institución, mail, contenido) deberán ser enviados hasta el 31 de agosto 2012. Se recomienda hacerlo con anticipación. Se podrá participar con o sin presentar trabajo. Se dispondrá de 15 minutos para presentar el trabajo

Comitivas-delegaçoes

La Internacional del Conocimiento espera recibir aproximadamente comitivas de estudiantes de graduaçao de unas 50 ciudades Al congreso 2010 concurrieron varias delegaciones de estudiantes de numerosas ciudades de Argentina, Bolivia, Brasil, Chile, Costa Rica, Colombia.

Organización de la comitiva

Se recomienda que se organice un equipo, de 2 o 3 personas, en cada ciudad o institución de educación superior que organice la comitiva y se comunique con la Internacional del Conocimiento, informando el interés por viajar al congreso

Equipo de Jóvenes Profesionales del Conocimiento

Es deseable que se aproveche la preparación para participar del congreso y de ese viaje intelectual para organizar un equipo permanente que promueva la realización de actividades especialmente destinadas a promover la investigación entre jóvenes. Este equipo puede permanecer ligado a la Internacional del Conocimiento, obteniendo así muchos beneficios de información y contactos.

Se organizará un Foro Latinoamericano de Estudiantes para pensar el futuro de la región, en relación a las tareas del estudiantado

Logamento-Alojamiento:

Instalaciones deportivas de la USACH, gratuito

Presentar carné estudiante universitari@ y certificado inscripción congreso

Pre-Inscribirse a través de comitivas-delegaçoes

Es necesario traer artículos de aseo y saco de dormir.

Inscripción

30 US o 17.000 pesos chilenos

Esta inscripción da derecho a materiales congreso, participación en todas las actividades académicas, presentación de ponencia, actividades recreativas, de convivencia, cóctel de bienvenida y asado-churrasco final.

Campanha Compromiso Intelectual

OJO: Si ya has adherido comunicar a tus colegas para que apoyen también. Necesitamos 10.000 adesoes-adhesiones. Manifiesto y datos en la pagina web.

Responsable: Mg. Eduardo Hodge Dupré: e.hodge.dupre@gmail.com

|

|

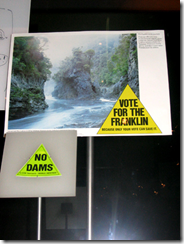

28 years ago, the Australian Supreme Court banned the construction of a hydroelectric dam in the Franklin River, Tasmania, in a case which came to be internationally known as Tasmania v. Commonwealth.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the unemployment rate in Tasmania was 10 per cent (the highest in the country), and the local liberal government together with some big businesses and industries saw the construction of the Franklin dam as the remedy for all evils. This, however, required the flooding of a unique ecosystem, which had been declared as part of the World’s Natural Heritage by UNESCO. Against the plan stood the members of the Wilderness Society and the nascent Green Party who, joined by a number of community associations and independent citizens, proposed a different path to growth: one based on the respect for nature.

Eventually getting the support of the national Labor Party, those opposed to the dam generated the largest environmental campaign in the history of this Southern country. Their main argument was that the dam would not only violate the country laws, but also international agreements to which Australia had subscribed. After five years of protests, lobbying and media work, they triumphed and their story became one of the most quoted in the history of environmental litigation.

I cannot help comparing this case with HidroAysén, a project from the Spanish multinational Endesa (subsidiary of Italian Enel) and Chilean Colbún, which involves the construction of five dams in Chilean Patagonia, to generate 2.750 megawatts –fifteen times more than the aborted Franklin Dam! Whereas the energy that was meant to be produced in Tasmania was at least destined for local consumption, in the Chilean case it is not the Patagonians who are going to get the benefits, but the capital, Santiago, and the big mining industries in the North of the country. After the controversial approval of the Environmental Impact Study of the dams last May, what is now under discussion is the other half of the project: namely, a transmission line of 2.300 kilometers that would cut through six national parks and 11 nature reserves, and would mean chopping over 20 thousand hectares of forests. If approved, this would turn out to be the longest line of direct current in the planet (and probably one of the most inefficient, losing an estimated 10 per cent of the energy on the way).

Some people are more prone to be convinced by arguments, while others are more easily persuaded by shocking images, powerful slogans and even musical jingles. The No Dams movement in Tasmania worked on both fronts effectively. On one hand, they won the support of public figures and intellectuals who repeated the message of what would be at stake if the dam were authorized. Together with the organizers, they led the protests, rallies and road blockades, and they even ended up in jail, together with hundred other campaigners. (At the peak of the movement, the Tasmanian prison system simply collapsed, unable to fit them all). Thanks to generous donations, the No Dams campaign could also be heard on the radio –Let the Franklin flow–, but arguably the most effective way to raise the public’s attention were the spectacular photographs taken by Peter Dombrovskis: emerald waters flowing down a rocky patch of the river, surrounded by dense forests and half covered by the early morning mist. “Could you vote for a party that would destroy this?”, was the question posed under the picture by the Labor party, in the federal elections of 1983. Few voters dared to answer in the affirmative, and Labor won with a large swing.

Some people are more prone to be convinced by arguments, while others are more easily persuaded by shocking images, powerful slogans and even musical jingles. The No Dams movement in Tasmania worked on both fronts effectively. On one hand, they won the support of public figures and intellectuals who repeated the message of what would be at stake if the dam were authorized. Together with the organizers, they led the protests, rallies and road blockades, and they even ended up in jail, together with hundred other campaigners. (At the peak of the movement, the Tasmanian prison system simply collapsed, unable to fit them all). Thanks to generous donations, the No Dams campaign could also be heard on the radio –Let the Franklin flow–, but arguably the most effective way to raise the public’s attention were the spectacular photographs taken by Peter Dombrovskis: emerald waters flowing down a rocky patch of the river, surrounded by dense forests and half covered by the early morning mist. “Could you vote for a party that would destroy this?”, was the question posed under the picture by the Labor party, in the federal elections of 1983. Few voters dared to answer in the affirmative, and Labor won with a large swing.

Another important point is that it was understood from the beginning that the decision whether to approve or reject the Franklin dam was not technical, but political. The solution could not come from a mere cost-benefit analysis, because what was at stake was something priceless, namely, what Tasmania wanted to be and to become. The Green Party and its founder, Bob Brown, clearly saw this and, after the battle was won, remained as crucial actors in the Australian political scene: today they are part of the governing coalition, and Brown is one of the most popular senators countrywide.

Finally, the campaign was not so much about opposing, but overall about proposing an alternative path to development. The No to the dam was a Yes to sustainable growth. Three decades later, the decision has proved to be correct. Today, tourism is the second major economic activity in that state, and gives jobs to half a million Tasmanians, it generates a billion dollars annually and it attracts almost a million visitors. Moreover, Tasmania is Australia’s leader when it comes to the production of renewable energy, which amounts to 87 per cent of its total. This comes mainly from wind farms and hydroelectricity (yes, hydroelectricity, but not from large dams, but from run-of-the-river power plants for local use).

How should the Tasmanian story illuminate the Chilean case? To start with, the Patagonia Sin Represas campaign has powerful arguments on its side. Among them, firstly, that what looks like the cheapest option in the short and maybe medium term will be the most expensive in the long term. Secondly, that HidroAysén is not the only alternative available to solve the country’s purported ‘energy shortage’, because we have other options in abundance, like wind, geothermal energy and sun. Thirdly, that if HidroAysén benefits anybody, it is not the Patagonians. And fourthly, that a number of recent studies show that big, old-fashioned dams like the ones planned are not the clean energy that they claim to be (given increased sediment build-up, the fragmentation of the river ecosystem which results on the massive death of fish, etc.). Patagonia Sin Represas has used all this arguments effectively, and it has also appealed to our senses through powerful images, like those of the beautiful rivers Pascua and Baker, where the dams would be constructed; the huemules, our national emblems who are now an endangered species and many of whom live in the five thousand hectares to be flooded; and the dramatic effect that the transmission line would have on some of the most pristine landscapes in Chile and the world. Moreover, just as the No Dams campaign, Patagonia Sin Represas has progressively won the support of the general public, transforming itself from a narrow environmental movement into a social one. The best example of this is that, after the initial approbation of the dams by the government, on the 10th of May, 30 thousand Chileans gathered in Santiago to march against the decision. In every regional capital from north to south, this support was replicated.

How should the Tasmanian story illuminate the Chilean case? To start with, the Patagonia Sin Represas campaign has powerful arguments on its side. Among them, firstly, that what looks like the cheapest option in the short and maybe medium term will be the most expensive in the long term. Secondly, that HidroAysén is not the only alternative available to solve the country’s purported ‘energy shortage’, because we have other options in abundance, like wind, geothermal energy and sun. Thirdly, that if HidroAysén benefits anybody, it is not the Patagonians. And fourthly, that a number of recent studies show that big, old-fashioned dams like the ones planned are not the clean energy that they claim to be (given increased sediment build-up, the fragmentation of the river ecosystem which results on the massive death of fish, etc.). Patagonia Sin Represas has used all this arguments effectively, and it has also appealed to our senses through powerful images, like those of the beautiful rivers Pascua and Baker, where the dams would be constructed; the huemules, our national emblems who are now an endangered species and many of whom live in the five thousand hectares to be flooded; and the dramatic effect that the transmission line would have on some of the most pristine landscapes in Chile and the world. Moreover, just as the No Dams campaign, Patagonia Sin Represas has progressively won the support of the general public, transforming itself from a narrow environmental movement into a social one. The best example of this is that, after the initial approbation of the dams by the government, on the 10th of May, 30 thousand Chileans gathered in Santiago to march against the decision. In every regional capital from north to south, this support was replicated.

The battle so far has not been easy, though, and will not be. Whereas in the Tasmanian case the company which proposed the project had limited resources to promote it, HidroAysén, backed by the multinational Endesa, has spent millions of dollars lobbying for and publicizing its cause. An important part has been to infuse fear in the population, through threats such as that we are going to be left in the dark, or that the country will not be able to grow if the project is not carried out. Against this, the only option for Patagonia Sin Represas is to stand as a truly social and political movement with the legitimate support of the citizenry. Regarding this point, another important difference with the Tasmanian case is that, while in the latter the political parties swiftly took sides for or against the Franklin Dam, the main political parties in Chile have only made lukewarm declarations in support or against the project. Discounting a couple of independent senators and representatives, it looks as if our politicians are dragging behind the times, unable to take a stance on the national problems that really matter. In the background, members of the right-wing government have been explicit on their support to HidroAysén, and have had no quibbles to use their position of authority to put the message through. Moreover, no Green Party has been born to work for this and other pressing environmental and social causes (whoever the Greens are in Chile, so far, they have not managed to capitalize on the many voices of discontent).

HidroAysén has still a long way to go before its definitive approval, and it is in the meantime that those who oppose it have to come with concrete alternatives. Together with the No to the dams in Patagonia has to come a Yes to other paths not only of energy production but, more widely, of development and even property rights over common goods (under Pinochet´s dictatorship, the Chilean waters were privatized, and it was thanks to this law that Endesa could acquire a significant amount of the water rights, especially in the area of the project). What is at stake here is not only one of the most pristine landscapes in Chile, but in the planet. The conclusion should be obvious: One Patagonia is worth more than a thousand dams.Author: Alejandra Mancilla, Chilean Journalist and PhD candidate in Philosophy, Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics (CAPPE), Australian National University, Canberra. www.alejandramancilla.wordpress.com

Chilean academic Claudio Coloma applies Peripheral Thought Theory to the response to Rabindranath Tagore to the Japanese defeat of the Russian forces in 1905.

Frequently, Rabindranath Tagore is known by his artistic work, especially in Latin America. This is demonstrated most obviously in his Nobel Prize in literature. But throughout his life, Tagore also had an important role in the area of non-fiction. Many works were composed to interpret the Indian and Asian political reality during the first half of the twentieth century. It is thanks to these works that it is possible to see the Western influence on Tagorian thought.

It is possible that the Western influence on Tagore’s thought came from two ways. First, Tagore, the Indian man, had to suffer with the European imperialism in Asia, and specifically in India. To have born and lived in a downtrodden people had to be a hard experience when a man, as Tagore, had knowledge about the historic greatness of India as well as of Asia.

Second, in spite of European imperialism, Tagore was able to discriminate between the European domination in Asia (specifically in India) and the virtues of the Western modern thought. In this sense, Tagore admired some Western ideas related to freedom and, in consequence, he was motivated to achieve a better Indian society.

To understand both the impact of European imperialism as the influence of the Western thought ways, it is necessary before to consider briefly the Peripheral Thought Theory[1]. This theory is used systematically to study the non-Western thought formulated especially in the last two hundred years. According to this theory, Europe is called the ‘centre’.

Thus, during this time we have been able to see Western influences and motivations, in cases where peripheral leaders, intellectuals and politicians have gone beyond their own cultural borders in order to think about the future, welfare or development of their own societies. Specifically this kind of thought has been yielded when non-Western thinkers have followed a special feeling of fascination, perplexity or rejection about the centre.

The peripheral intellectual thought has swung between two mainstreams like a pendulum: in one side, there have been intellectuals who have rejected the intellectual and cultural influence from West and at the same time have valued their own social and cultural roots. In the other side, there have been intellectuals who have yielded ideas with the purpose to imitate aspects from West into fields such as policy, economy, or culture.

The first way of the Peripheral Thought is called “Identitario” which means “be like us”, whereas the second way is called “Centralitario” which means “be like the Centre”. According to this theory, this dilemma is the main feature of the non-Western thought and it would be most important than another academic dilemmas such as Negro/White, Rich/Poor or Women/Men, because this kind of oppositions can be analyzed thanks to this two notions of Peripheral Thought Theory.

Another important feature of this theory is that, in spite of that the intellectual peripheral production around the world has rejected or approved the Western culture, at the same time among peripheral intellectuals there have been a common perception that the West is the most powerful social formation.[2]

Some of main works in which we can see the Western influence on Tagore´s non-fiction ideas are “Nationalism”, “Greater India”, “The problem with Non-Cooperation”, “Crisis in Civilization” and “The Spirit of Japan”.

According to Tagore, Europe had increased its power over Asia. This reality meant humiliation. But paradoxically, this humiliation was not produced by Europe´s dominion over Asia; the root of the humiliation was could be found into Asia.

As one adherent of Pan-Asianism´ ideas, Tagore thought that Asia has been a more successful society than Europe, but this situation changed because Asia stayed in the past without progress; to Tagore Asia “is like a rich mausoleum which displays all its magnificence in trying to immortalize the dead (…) For centuries we did hold torches of civilization in the East when the West slumbered in darkness (…) then fell the darkness of night upon all the lands of the East”.[3]

It was not new say that the West was not guilty, or at least, that West was not the prime culprit for Asian humiliation. Throughout the history of India, several Indian intellectuals, from Rammohan Roy until Hamid Dalway, including Syed Ahmad Khan, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, B.R. Ambedkar, Rammanohar Lohia have written about the roots of problems of India, which in turn were firstly the caste system, religion struggles and gender injustices, and then were problems related with the independence from United Kingdom.[4].

But, the worth of Tagore´s ideas, compared with his countrymen, was his interest on Asia and not only on India, for this reason is important his intention to establish the Pan-Asian movement. In this sense, Tagore´s connection with many intellectuals from the rest of Asia was important, especially with Japan, because this country was an exceptional case after Meiji´s Reforms. Basically, the Japan of Meiji had been the period in which this country was able to successfully achieve "Modernization".[5]

Thanks to its success, Japan became a new magnet to many peripheral intellectuals. There were two Japanese organizations that had a key role in this achievement: Kokuryukay and Genyosha. According to Cemil Aydin, both organizations fostered ties with many nationalists and intellectuals from Asia; one of them was Rabindranath Tagore[6].

The summit of Japanese modernization process was the triumph over Russia at war of 1904-1905. Many intellectuals thought after triumph that it was possible to be free from the Colonization and retake the self-government. The impact of the Russo-Japanese War crossed the East Asia borders and was able to achieve inspiration from leaders of West-Africa, black leaders in the USA, Muslims, Indian, and other peoples.[7]

Thanks to his special relationship with Japanese intellectuals (one of them was the father of Pan-Asianism, Okakura Tenshin) Tagore was not indifferent to the Japanese triumph. In respect of this, Tagore wrote “One morning the whole world looked up in surprise, when Japan broke through her walls of old habits in a night and came out triumphant”.[8]

But he was not totally at ease with the celebrations of Japanese triumph. In fact, Tagore became worried about the Japanese nationalism that strongly emerged after 1905, because nationalism was enemy of heterogeneity of Asia, especially in India. According to Tagore, nationalism was the root of violence. Furthermore, after victory, Japan colonized Manchuria and Korea (1910). According to Tagore, if in India people acquired these kinds of fanaticisms, the consequences could be devastating[9].

Thus, Tagore rejected the Japanese attitude, and by contrast to his first impressions, he stated: “I have given up Japan. I feel more and more sure it is not the country for me”.[10]

What was the reason to declare this? The reason would have been: Japan adopted the modernization with “all its tendencies, methods and structures, and dream that they are inevitable”. That is, thanks to the Meiji Reformsm Japan had to be a new creation and not a mere repetition. To be a copy was like wearing the skeleton with another skin.[11] Their modernization meant a deception because the main difference between Asia and West was the use of wisdom, work and love versus the use of violence.

Despite the deception, the Japanese experience and the contact with West were not always unfortunate facts, because it was possible to understand that the world needed the values of India and of the rest Asian peoples. Thanks to this understanding, it would have been possible re-light the torch of civilization in the East and put an end to humiliation.

Six years before that Tagore wrote “The Spirit of Japan”, where he warned on Japanese menace. He wrote a series of essays (1909-10) about the meeting between India and the Englishman. In these essays Tagore wrote about expectations that India could achieve thanks to its encounter with the West: “On us to-day is thrown the responsibility of building up this greater India, and for that purpose our immediate duty is to justify our meeting with the Englishman. I shall not be permitted to us to say that we would rather remain aloof, inactive, irresponsive, unwilling to give and to take, and thus to make poorer the India that is to be”.[12]

Tagore thought that “in the heart of Europe runs the purest stream of human love, of love of justice, of spirit of self-sacrifice for higher ideals (…) in Europe we have seen noble minds who have ever stood up for the rights of man irrespective of colour and creed”. These Europe´ good features were countered with a contrary tendency—“supremely evil in her maleficent aspect where her face is turned only upon her own interest, using all her power”.[13]

Certainly, the concept of freedom was the best aspect of Europe and this notion complemented Indian concerns with injustices related to caste system, the Untouchables´ situation, Muslim-Hindu disputes, and gender differences. In this sense, India had to learn from West.

In addition, Tagore admired the European literature and art for its beauty, because both mean “fertilizing all countries and all time”.[14] According to Tagore, both freedom and culture beauty were seen as an opportunity to get a balance between spirit and material things. But, unfortunately to get this purpose would be difficult thanks to temptations of power. In this sense, reviewing the Japanese experience, this country was a failed instance: “unfortunately, all his armour is not living, some of it is made of steel, inert and mechanical. Therefore, while making use of it, man has to be careful to protect himself from its tyranny”.[15]

One successful instance of benefits of European culture, which in turn was learnt by India, was the reign of law. The law meant the balance between power and freedom, because the British government established order (or at least more stability) and respect among castes, colours and religions. Nonetheless, according to Tagore, this instance would be mirror of the spirit of the West and not of the nation of the West.[16]

To be fair, his estimation of European civilisation did not imply that there was only one alternative. Tagore was concern to be clear on this point. In this sense, his speech entitled “Crisis in civilization” is emphasises the existence many civilizations with noble purposes, such as Japan (despite its failures) Russia, Iran, Afghanistan or China[17].

Finally, reviewing Peripheral Thought Theory and this small sample of Tagore´s ideas, it is possible to state that this Indian intellectual was a man who strove to achieve a balance between ideas from the Centre and the Periphery.

This point is important if it is considered that Tagore is mainly known as a poet and mystic man, at least in Latin America, instead of as a non-fiction author who was able to state original points of view about the encounter between different civilizations.

Thus, the Tagorian thought was able to be “Centralitario” or “Identirario”. His main concern was the thread to the freedom of downtrodden peoples across Asia. Hence Tagore was able to “be like the Centre” or “to be like us”, demonstrating that he had an open mind to understand and to explain the complicated reality of Asia at the first half of past century.

[1] The Peripheral Thought Theory have been proposed in Chile by Eduardo Devés, from the beginning, as an academic parameter to study the Latin American thought throughout the 20th Century, but actually this theory is being used also to research about contemporary Asian and African thoughts, in order to achieve a global perspective and a best understanding about the non-Western thought. Eduardo Devés Valdés, “El Pensamiento Latinoamericano en el siglo XX”, 3 volúmenes, Editorial Biblos, Buenos Aires, 2000-2004.

[2] Devés Valdés, Eduardo, “Las disyuntivas del pensamiento latinoamericano y periférico”, Seminario de Investigación Interdisciplinaria. Facultad de Estudios Generales, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto Río Piedras. Ciclo de conferencias Octubre-Diciembre 2006. p.1.

[3] Tagore, Rabindranath, “Nationalism”, Norwood Press, USA, 1917, p.65-66.

[4] These priorities can be demonstrated in Ramachandra Guha´s book entitled “Makers of Modern India”, Penguin Books, India, 2010.

[5] Understanding “Modernization” as a concept from the West.

[6] Cemil Aydin, “The politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia”, Columbia University Press, USA, 2007, p.57.

[7] Coloma, Claudio, “Disyuntiva y reivindicaciones periféricas ante el impacto de la Guerra Ruso-Japonesa”, Universidad de Santiago de Chile, Santiago de Chile, 2010.

[8] Tagore, Rabindranath, “The Spirit of Japan”. Sisir Kumar Das editor, “The English writings of Rabindranath Tagore, volume three, a Miscellany”, Sahitya Akademy Edition, New Delhi, 1996.

[9] Sen, Amartya, “Tagore y la India”, Fractal nº10, julio-septiembre, 1998, año 3, volumen III, pp. 121-168.

[10] Rabindranath Tagore´s letter addressed to C.F. Andrews, 11th June, 1915, cited by Patrick Colm Hogan & Lalita Pandit, editors, “Rabindranath Tagore: universality and tradition”, Associated University Press, USA, 2003, p.47.

[11] Op.cit.

[12] Rabindranath Tagore, essay includes in Ramachandra Guha´s book entitled “Makers of Modern India”, Penguin Books, India, 2010, p. 189.

[13] Op.cit, p.195.

[14] Op.cit, p.194.

[15] Rabindranath Tagore, “The Spirit of Japan”, ManyBooks.net, 1916, p.5.

[16] Rabindranath Tagore, essay includes in Ramachandra Guha´s book entitled “Makers of Modern India”, Penguin Books, India, 2010, p. 198-199.

[17] Rabindranath Tagore, speech includes in the Rakesh Batabyal´s book entitled “The Penguin Book of Modern Indian Speeches: 1877 to the Present”, Penguin Books, India, 2007, p.453-459.

II Congress on Sciences, Technologies and Cultures: Dialogue among the Disciplines of Knowledge

Looking at the future of Latin America and the Caribbean

October 29 and November 1 ,2010 at the Universidad de Santiago de Chile USACH

The Study Net on Migrations, Nationalism and Citizenship (USACH 2008) invites you to take part in the Symposium.

The Challenges of Globalization. Conceptual, Historical and Present Problematic Prospects regarding Migrations, Citizenship and Nationalisms in Europe and America.

Coordinators:

The political, economical, social and cultural transformation of the last thirty years have placed some concepts again in the centre of the discussions about the challenges provoked by the so-called “global era”. Changes in historical configuration which today question the existence of the Nation-State, the interaction and interconnection between people and organizations through markets and global informatic nets, the questions around cultural diversity, the problematic of migrations and its relationship with the rebirth of nationalisms and the crisis of the concept of citizenship worked out in modern times invite researchers to reflect jointly on these problems, their history, their present and their future.

With the summons we continue with reflections began at the symposium which took place at the I International Congress on Knowledge (Santiago de Chile 2008) and the 53rd Americanist Congress (Mexico 2009) which resulted in the creation of a Net (www.internacionaldelconocimiento.org) and the publication of a recently edited book which takes the most significant ideas of the I International Congress on Knowledge.

We invite colleagues of all disciplines who work on these subjects to participate. Those papers which deal with conceptual, methodological, historical and present problematics of Diasporas, and Migrations will be especially welcomed. Proposals will be received in Spanish, Portuguese and English.

Paper summaries are accepted (200 words) and institutional ascriptions up to June 30 2010. Papers (15 pages max.) up to August 31, 2010. Only approved papers will be accepted at the symposium.

Chile has a lively publishing industry that produces serious non-fiction on cultural themes, often Latin American, particularly Chilean. Given the issues of language and subject, these works are rarely read outside Latin America. The leading art theorist Ticio Escobar, for instance, is hardly translated into English at all.

Sometimes there are books that are both uniquely Chilean but potentially also universal in their particularity, at least to fellow countries of the colonised South. Oscar Contardo’s Siútico: Arribismo, abajismo y vida social en Chile (Santiago: Vergara, 2008) seems at first inscrutable. The title itself is a word only found in Chile. The other words are hard to find in English – ‘upism’, ‘lowism’? Yet its analysis of the way a colonial class attempts to distinguish itself from the upwardly mobile, first by elitism and then by a kind of poverty chic, has compelling parallels to the social dynamics in other colonial cultures.“Siútico” es un chilenismo de origen oscuro y etimología incierta. Apareció a mediados del siglo XIX como un adjetivo burlón para señalar personas —sobre todo varones— que pretendían ser tomados por elegantes sin pertenecer a la clase alta chilena. Es una palabra cuyo sinónimo más cercano en castellano es “cursi” o “arribista”, pero que por el hecho de ser chilena encierra matices propios de nuestra sociedad. Chile en el siglo XIX era una sociedad agraria, socialmente muy rígida en donde las riquezas nuevas de los mineros del norte sacudieron las costumbres campesinas, sobrias de la elite del “valle central”. Así como la palabra expresión inglesa “snob” le debe mucho a la revolución industrial y al surgimiento de una burguesía en Inglaterra, la palabra “Siútico” en chile le debe otro tanto a los nuevos ricos de los minerales de plata descubiertos a mediados del siglo XIX y a una cierta (y pequeña) clase media burócrata.

“Siútico” is a Chilenism of obscure origin and uncertain etymology. It appeared in the mid-nineteenth century as an adjective to indicate ridiculous people — especially males — who claimed to be taken by elegant without belonging to the upper class in Chile. It is a word whose synonym is closest in Castilian “cursi” or “arribista”, but due to the fact of being Chilean it contains nuances particular to out society. Chile in the nineteenth century was an agrarian society, socially very rigid, where the new wealth of miners of the north challenged the peasant habits, the sober elite of the “Valle Central”. Just as the word “snob” owes much to the industrial revolution and the emergence of a bourgeoisie in England, the word “Siútico in Chile owes as much to the new rich of minerals of silver discovered in the mid XIX and a certain (and petty) middle class bureaucrat.

El abajismo lo describo como un fenómeno que ha atravesado de distintas maneras la historia de Chile. Se trata de una expresión que describe la identificación de ciertos personajes de la elite con la vida propia del pueblo llano, de las clases medias y bajas. La historia de la izquierda chilena está salpicada de ilustres apellidos de clase alta. En su mayoría hombres (el ingreso de las mujeres al espacio público es reciente) que abrazaron la causa de los desamparados desde la política (el mismo Salvador Allende, Carlos Altamirano y otros tanto). Esto tuvo su vertiente religiosa sobre todo a partir de los 60 con sacerdores “obreros” como el padre Puga o el Padre Aldunate. Los últimos síntomas de abajismo tienen menos carga ideológica y una mayor tendencia estética: es el turismo de clase que emprenden jóvenes en antros de bariios populares. La “vida del pobre” es vista como algo interesante, “trendy”, verdadero. Hay una línea piadosa del abajismo que toma ciertas nociones del “cura obrero” pero en donde los elementos revolucionarios aparecen diluidos por el neo asistencialismo. Esto se ve mucho entre alumnos de ciertas universidades caras (no hay universidades gratuitas en Chile) que organizan trabajos de verano o jornadas de ayuda durante los fines de semana en barrios marfginales. Son una suerte de “visita a la realidad” frecuentemente auspiciadas por organizaciones católicas.

I described it as a phenomenon that has taken different paths in the story of Chile. It is a term that describes the identification of certain characters in the elite with the life of ordinary people, from middle and lower classes. The history of the Chilean left is peppered with famous names of high class. Most men (women’s entry to the public is recent) embraced the cause of the disadvantaged from politics (as Salvador Allende, Carlos Altamirano and both). There was an especially religious dimension from 60s, with priest “workers” such as the father Puga or father Aldunate. The latest symptoms of abajismo are less ideological and more inclined aesthetics: it is the young class tourists who visit the dens of popular suburbs. The “life of the poor” is seen as something “trendy”, true! There is a pious version of abajismo that takes the certain notions of “worker priest”, but where the revolutionaries are diluted by the new welfarism. This is seen widely among students of certain expensive universities (there are no free universities in Chile) who organize summer jobs or day jobs during the weekends in marginal neighbourhoods. They are a kind of “reality tour” frequently sponsored by Catholic organizations.

Sobre esta pregunta está implícito el juicio de que hay formas válidas y otras que no. La verdad a mi no me interesa entrar en ese esquema, sino en el análisis del fenómeno. Yo creo en la libertad de la gente en adherir a causas legales y en expresar sus inquietudes sociales de la mejor forma. También creo que dada la importancia del problema social en Chile (pobreza, desigualdad, discriminación) es necesario tener posturas críticas sobre el punto.

On this question is the implicit view that there are valid and others not. Actually I do not interested in engaging with this proposition, but in the analysis of the phenomenon. I believe in the freedom of people to adhere to legal reasons and express their social concerns in the best way. I also believe that given the important social problem in Chile (poverty, inequality, discrimination) it is necessary to take critical positions on this matter.

No, no lo creo. Se da de manera difrenete eso sí. En Latinoamérica debe haber variaciones que tienen que ver con la propia historia del país, su demografía, economía y desigualdades. Latinoamérica tiende a ser mirada como un todo sin distinción básicamente porque es “mirada” desde fuera. Es una región de sociedades que comparten muchas cosas, pero que difieren en otras tantas. Creo, sin embargo, que la desigualdad y la discriminación son dos ejes comunes que se expresan de manera distinta.

No, I do not think so. But it’s style is different. In Latin America there must be changes that have to do with the history of the country, its demography, economy and inequality. Latin America tends to look uniform as a whole because it is basically seen from the outside. It is a region of societies that share many things, but they differ in others. However, I believe that inequality and discrimination are two common axes that are expressed differently.

El libro ha sido un éxito que no me esperaba. La crítcia lo recibió muy bien, y lleva casi un año entre los más vendidos. Mis compatriotas tienen una cierta inclinacíón por leer libros en donde puedan reconocerse, sobre todo en sus pequeñeces, odios y venganzas. Debería existir un género sobre el tema. Un apartado en las librerías que se llamara “en qué consiste ser chileno”. El rol del código secreto, el sobre entendido, la crueldad disfrazada de buen tono, el aislamiento geográfico como factor de asfixia histórica, el racismo galopante y a la vez negado, el aburrimiento como valor y el pánico por la imaginación.

The book has been more of a success than I expected. The critics received it very well, and it is nearly a year among the top sellers. My compatriots have a certain inclination to read books where they can be recognized, especially in the little things, hatred and vengeance. There should be a genre on the subject. A paragraph in the book is called “what it takes to be Chilean.” The role of the secret code, on the understanding, cruelty disguised as good tone, geographic isolation as a factor of its stifling history, rampant racism and at the same time, boredom as value and panic in the place of imagination.

Similares creo que no. Estoy un poco intoxicado con el tema y necesito sacarlo de mi sistema para no terminar estallando en la calle.

I don’t think anything similar. I am a little intoxicated with the theme and I need to get it out of my system so as to not end up in the street.

The ideas themselves were hardly revolutionary, but provide extra support to leaders now as they attempt to find a common set of values. You can download their handbook of ideas here, which articulates familiar positions such as the need to resist protectionism, international equity and financial market governance.

In many ways, it was the location of this event as much as its content that made the intended statement. According to the Economist, ‘The fact that the meeting was being held in the southern hemisphere for the first time was also seen by some as a symptom of the world’s changing balance of power.’

The event’s organisers, Policy Network, had hosted four previous events in the north. But with the partnership of Michelle Bachelet, this time choose to locate the discussion on the other side of the world.

Where is this leading? In a discussion between the organisers, Roger Liddle, an advisor to Tony Blair, muses on where to meet next…

Liddle: Where do you think we can go that’s even further away? Australia?

As he chuckles at the prospect, Olaf Cramme quickly tries to quell the offense by turning it into a serious proposition. But it was certainly not intended as one. Prime Minister Kevn Rudd certainly hopes to be taken more seriously in London this week.

This is another example of the challenges Australia faces in finding a place for itself somewhere between the North and the South.