To give you some sense of where I am coming from, I have always worked in what is now known as science studies, and in particular within the sociology of scientific knowledge (SSK). My overarching interest has been with looking at the ways in which people, practices, and places are moved and assembled in differing local knowledge traditions. So I see my work and that which the Latin American historian Santiago Castro-Gomez has labelled ‘Coloniality of Power’ Group, as having a key question in common– how to work with the multiplicity of knowledges without subordinating them in the panoptic archive of western science.[1]

A guiding principle of SSK has been ‘things could be other than they are’, accordingly that which seems self-evident, natural, true or authoritative requires examination and explanation. The historical understanding of South America, like the global south as a whole, Australia included, has been frequently enmeshed in the self-evident and naturalising assumptions of Eurocentric explanations of the emergence of complex societies and civilization, of what civilisation consists in and how it came to be. This is especially apparent in the méconnaissance and violent misrecognition surrounding knowledges, spaces and rationalities in the narratives of prehistory within which South America has been framed.[2] South America has been variously portrayed as the last continent to be ‘discovered’, a ‘New World’, a pristine wilderness, as inhabited by primitive natives without civilization, though with the acknowledged exception of the Incas. Not only has South America been continuously subjected to the most extreme forms of violent conquest and exploitation since Columbus chanced upon it, but our understandings of it have been shaped within a narrative of a universalizing knowledge tradition and an abstract space, perhaps the most egregious and disturbingly popular being Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel.[3]

However, such narratives have been substantially challenged from a number of directions. First and foremost have been the challenges from South American critics, authors, and indigenous activists including Jorge Luis Borges[4], Edmundo O’Gorman[5], Arturo Escobar[6], Walter Mignolo[7], Enrique Dussel[8], Eduardo Viveiros de Castro,[9] and the movements leading to the establishment of The Intercultural University “Amawtay Wasi” (UIAW) of the Indigenous Nationalities and People of Ecuador[10], all of whom, in various ways, aim to destabilise the dichotomies under which the hierarchical hegemony of a unifying and universalising western science is established. They pose differing oppositions of unity and multiplicity in their conceptions of ‘agonistic pluralism’, ‘transmodernity’, ‘diversality’, ‘interculturality’, ‘multinaturalism’. Other challenges have come from a rethinking of the peopling of the world, the origins of complexity, modernity and civilization, that have emerged along with the geneticisation of history and archaeological work in Africa and the Near East. But it is the debates and controversies surrounding recent archaeological and historical ecological research in Norte Chico and Amazonia, and their articulation in understanding the emergence of complex societies and what constitutes civilization that are the central concerns of this paper. Naturally this concern carries with it a reflexive corollary: can an explanation of complexity in terms of emergence avoid simply being an extension of a universalizing knowledge tradition on the one hand, while avoiding a vitiating proliferation of multiplicities on the other?

A number of assumptions have served to preset the narratives of prehistory. Among them are the assumption that early man had little agency and was subject to population and environmental pressures, climate change, resource supply and geography, and that agency was only fully achieved with settlement and the invention of agriculture. This ‘sedentarist’ metaphysics reinforces the dominant orthodoxy that the Neolithic revolution was the precondition of civilisation and modernity, and was largely a Mesopotamian phenomenon.[11] Though counterparts in the East were acknowledged, the natural supremacy of Europe was assumed, because, at least according to Diamond, Europeans were geographically advantaged by being able to spread their domesticated crops and animals latitudinally. They were also lucky enough to have a climate and environment that encouraged them to sleep with their animals and thereby acquire immunity to infectious diseases. All they needed was to invent steel and the world was theirs.

This narrative underpins a particular conception of modernity and rationality that ties it to being settled in place — particularly Europe — and to building cities, establishing the rule of law and creating hierarchical states. Fixity in space and place has become the foundation stone of western rationality and epistemology. Consequently unrestrained movement is equated with wandering, irrationality, placelessness and the primitive, something that needs to be controlled, located and set in logical, linear order.[12] It is now possible to pose a counter narrative in which movement is given greater salience, and in which the notion of revolutions, especially the European Neolithic revolution, as foundation of modernity are undermined by recent archaeological work in South Africa, Turkey, and South America.

Arguably one of the key components on which all forms of movement depend is a social technology of kinship – a network of relatedness, bonding, and obligations that enables the transmission of resource access and knowledge across generations through a classification of friends, enemies, and strangers. Such conceptions of kinship and relatedness are social and cultural constructs and do not necessarily map naturally onto genetic and biological relationships. However, the development of such complex forms of social cognition is, Clive Gamble suggests, a prerequisite for overcoming the limitations of co-presence and extending relationships in space and time. A view that is consonant with Robin Dunbar’s ‘social brain hypothesis’.[13] Dunbar argues that ‘Primate societies are implicit social contracts established to solve the ecological problems of survival and reproduction more effectively than they could do on their own. Primate societies work as effectively as they do in this respect because they are based on deep social bonding that is cognitively expensive. Thus it is the computational demands of managing complex interactions that has driven neocortical evolution.’ This conception of the dynamics of human neocortical evolution as social rather than simply technological or biological fits well with both the model proposed by Stanley Ambrose for the co-development of language, symbolisation, a larger brain, and compound tool-making that began in Africa around 300,000BP, and with Ben Marwick’s claim that language and symbolisation developed with the extension of exchange networks.[14] In large part the symbolisation and feedback essential to the development of such social networks depends on keeping track of relatedness and kinship through forms of telling – performing and representation, storytelling, singing, dancing, painting, building, and, importantly for my argument, weaving.[15]

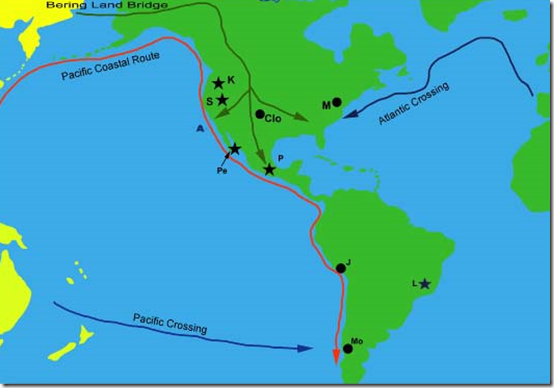

The narrative of human dispersals around the world simply as mass migrations or demic diffusions, can now be countered with a more complex narrative. One in which human movements are seen a relatively fast and strategic, demonstrating great flexibility in a diversity of environments, necessitating complex information exchange systems that allow group decision making and feedback, but without the necessity for hierarchy or plans.[16] Such information-exchange systems typically exhibit forms of emergent complexity in which relationships, language, materials, genes, places, practices and people are co-produced in the process of human movement.[17]

Correspondingly there are at least two possible frameworks, with multiple dimensions, within which to understand the origins of social complexity, modernity, and the relationship of knowledge and space. In a heterarchical framework social order can be understood as an emergent effect of a complex adaptive system. While a hierarchical framework implies that systemic superstructural forces produce social order. In turn heterarchical models have a dynamic based in multiplicity and difference, while hierarchical models are totalizing. I would argue that the answer to how work with multiplicity is not to simply favour the heterarchical, but to hold these two frameworks in the kind of tension of agonistic pluralism advocated by Dussel, that would allow for emergent knowledges and spaces.

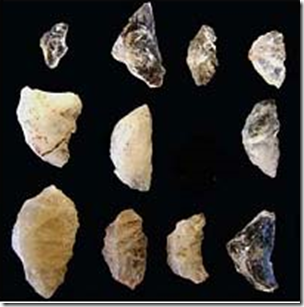

To date production of universalising scientific knowledge has been a narrative of dependency on a tightly demarcated organisation of abstract space and regularized movement. However, the naturalization of this narrative of space, time and knowledge subserving an account of European modernity is now countered by recent discoveries at the Blombos Cave and Pinnacle Point in Southern Africa which reveal that the behaviours that have been claimed to make humans ‘modern’ such as sourcing, combining, and storing materials that enhance technology or social practices, along with external symbolization and religion, occurred, not in Europe after a Neolithic revolution, but 100,000 years ago, before humans ever left Africa.[18]

While recent excavations in Turkey and Jordan suggest that the sequence of settle down, invent agriculture and only then are complex and hierarchical structures and societies possible is not the way things worked out in every case, rather there appear to have been a diversity of approaches to living and working together, including examples of building complex structures without agriculture or settling down.[19]

There is no time here to expand on the evidence for alternative paths to complex societies in the Near East, or on the evidence of human movements by sea in prehistory.

However, the revision of the view that human movement around the globe was largely by land, opens up the possibility of a much earlier time frame for the peopling of South America no longer constrained by an impassable barrier in eth Bering Straits. As early as 30,000BP people could have been coasting on the ‘kelp highway, with multiple groups overlapping each other along the coast and penetrating the interior simultaneously.[20]

It also lends strong support to Michael Moseley’s controversial ‘Maritime foundation of Andean civilization’ (MFAC) hypothesis, that is at the heart of the debate over Caral which, with its impressive size and massive pyramids and plazas, is now variously proclaimed the ‘oldest city’ or ‘oldest civilization in the Americas’, even ‘the oldest in the world’ and which is the main focus of this talk.[21]

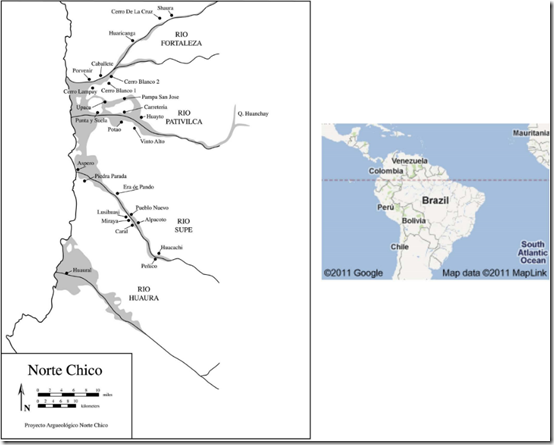

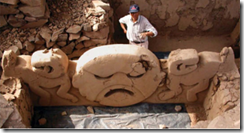

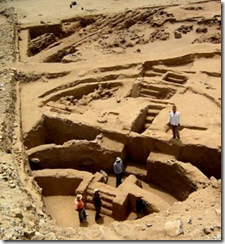

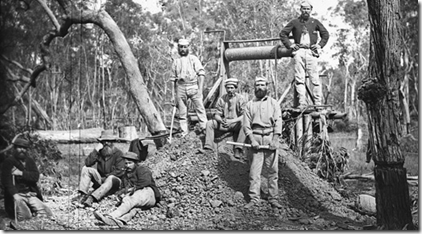

The area of coastal Peru north of Lima, now known as Norte Chico, was first noted as significant in 1905. Aspero, the site at the mouth of the Supe river on which Caral stands, was excavated in 1941 by Willey and Corbett. Much to their subsequent embarrassment Willey and Corbett simply failed to recognise the existence of pyramids at the site, dismissing them as ‘natural eminences of sand’.[22] The site did not excite much attention because it was pre-ceramic, having no pottery or gold; it was also in an arid cold desert. It simply didn’t rate as a site of a possible civilization.

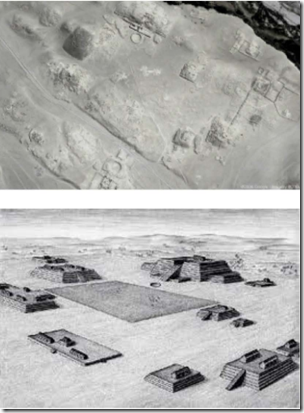

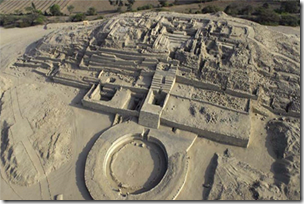

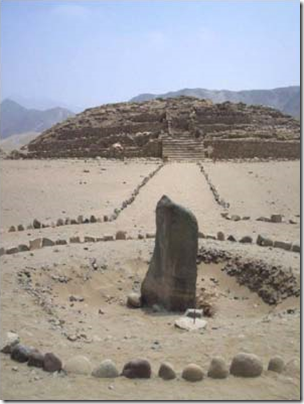

It was not until the late 1990s that the single-minded persistence of the Peruvian archaeologist Ruth Shady revealed its full complexity and extent with multiple, massive pyramids, temples, plazas and residences. Interest in Caral became intense when Shady published the dating results in Science in 2001 with the help of Jonathon Haas and Winifred Creamer from the Field Museum in Chicago.[23] At 2900 BCE it was declared ‘the oldest civilization in the Americas’, making Caral one of the oldest civilizations in the world. At this period the only other site with that degree of urban complexity was Sumer in Mesopotamia.

Haas and Creamer have turned their attention to revealing the complex of sites in adjacent valleys, and to articulating an alternative explanation to Ruth Shady’s for the emergence of this society, while Shady has continued to excavate Caral. Despite a growing rivalry and differing explanations, Shady and Haas/Creamer have taken each other’s work into account and have more in common than their apparent differences.[24] The importance of Caral lies in the fact that much of what has been found does not fit with the orthodox understanding of the emergence of a complex society, of civilization. The same can be said of recent work in Amazonia.

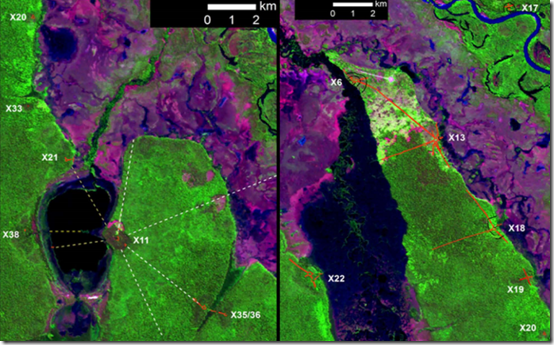

Much to everyone’s surprise historical ecologists, archaeologists and anthropologists, Anna Roosevelt, William Denevan, Clark Erickson, William Balée and Michael Heckenberger have found evidence of the fabled civilizations first reported by Francisco de Orellana in his extraordinary voyage down the Amazon in 1541. The region may have had a population of 4-5million, but who, in a wavefront of disease, possibly smallpox, disappeared ahead of full-scale Spanish invasion. Such large populations, it is claimed, were made possible by the total and deliberate transformation of what would be otherwise rather difficult and restricted ecosystems with very poor soil subject to severe flooding. The Amazon, on this account, is not a pristine wilderness, but an anthropogenic construct, a performative landscape with spatial, temporal and epistemological dimensions, a co-production of human agency, knowledge practices, movement and the environment. Until recently what has gone unnoticed, seemingly invisible in the dense rainforests, were the massive complexes of geometrical earthworks, mounds, causeways, canals, roads, fishtraps and terra preta.[25]

These earthworks and soil transformations enabled the proliferation of large interlinked urban settlements. Around the Amazon and its tributaries in the floodplains (varzea) the dark earth (terra preta) mounds, carefully and deliberately created out of soil mixed with charcoal, broken pottery, fish and food remains and human excreta, were superbly fertile, allowing the abundant growth of food crops.[26]

At the same time geometrical earthworks or geoglyphs are starting to become visible in upland areas of the Amazon (terra firme) as they are exposed by forest clearing and archaeology’s newest research technique Google Earth. These massive constructions are most likely to be performance spaces, though there is some possibility that they had defensive functions. Whatever their function the researchers anticipate finding thousands more such structures, revealing a completely unexpected degree of social complexity in a region held to have been only capable of supporting simple villages.[27]Now that the first round of what Denevan calls the ‘Amazon archaeology wars’ has been won, and the presence of these vast complexes has largely been accepted, what remains at issue is how and why they could have been built. The critics argue that the massive earthworks would have required a correspondingly massive workforce, which in turn would have necessitated a hierarchical social structure and division of labour, typical of state-level societies, along with an augmented food supply, i.e. agriculture,

Erikson, Heckenberger and Roosevelt have shown that there is evidence of augmented food supply, but agree there is no historical or ethnographic evidence of such hierarchical social structures in Amazonia [28] They suggest the earthworks, were built by heterarchical societies: groups of communities, loosely bound by shifting horizontal links through kinship, alliances, and informal associations. For Heckenberger these were ‘self-organising autonomous polities in a distributed system’, for Erickson the result is ‘the accumulated landscape capital of generations of farmers who built it more or less on their own’. [29]

In my own work I have similarly argued that complex structures like the gothic cathedrals did not, in the first instance, require either a master architect or a plan, they were the result of the ‘ad hoc accumulation of the work of many men’.[30] However, I would also argue that these communal activities have to be understood performatively. These communities were creating knowledge spaces, enabling people, practices and places to be linked together. They socialised the landscape through performance of a collective social identity.[31]

At Norte Chico the evidence is more equivocal. Norte Chico is of great importance because of its special features, not just its surprising age. It is built in one the most arid environments on earth, which would seem to lend support to Moseley’s MFAC hypothesis based on the superabundance of anchovies, sardines and molluscs on the Peruvian coast. However, Shady’s discoveries at Caral and Haas and Creamer’s at other inland sites in Norte Chico reveal a complexity that caused Moseley to modify his claim that ‘it’s all based on fish’. All the sites are centered on irrigation utilising the seasonal floodwaters of the four main rivers coming down from the Andes. While some food crops were grown in these irrigation areas, the dominant crop was domesticated cotton. Despite Haas and Creamer’s claims that their inland sites are as old as, and outnumber the coastal ones, and[V1] that hence the maritime hypothesis cannot hold, it seems plausible to claim that the region displays a unique example of co-dependency.[32]

Fresh sites of greater age are being found, on the coast, inland, and in the mountains as attention has become focused on Norte Chico, at Sechin Baja at Casma, Buena Vista, Bandurria and Chankillo for example.[33] These sites suggest that initially they were autonomous, though right from the earliest stages they were linked in trading networks exchanging exotic goods up and down the coast, inland into the mountains, possibly even to the Amazon.

Shady’s and Haas and Creamer’s attraction to a hierarchical explanation of social complexity may in part be rooted in their attempt to attribute a special iconic status to Norte Chico as a ‘mother civilisation’ on the grounds that, unlike any other, it grew in isolation from outside influence.[37] The trading networks and exchange systems which would have been established through the movements and interactions of the region’s earliest occupants, as a precursor to social complexity, make such miraculous births seem as unlikely as ‘neolithic revolutions’ and ‘pristine wildernesses’, whilst they also undermine the apparent corollary of seeming to have done it all by themselves, and that there must have been an elite to direct it.[38]

Autonomous communities and exchange networks aside, the evidence seems to show that the inland communities’ basic source of protein was fish, and for the coastal communities to supply that volume of food they had to have nets, nets made[V2] from cotton domesticated and grown in irrigated plots inland. Over time what may have developed was a relationship of co-dependence rather than dominance by one or the other. Equally problematic is the qustionof how the labour force was organised to build this massive complex of monuments[V3] ?

For Haas it’s straightforwardly obvious: The size of a structure is really an indication of power…People don’t just say, ‘Hey, let’s build a great big monument.’ They do it because they’re told to and because the consequences of not doing so are significant.[39] Shady is likewise in no doubt, it was a proto-state run by an elite in the service of a religious ideology: ‘Religion functioned as the instrument of cohesion and coercion, and it was very effective’[40] But her key claim for the necessary existence of an elite hierarchy dominated by religious and scientific experts is that Caral was laid out in a specific spatial plan based on astronomy and a calendar.

[t]he arrangement of architectural structures implies a spatial ordering that preceded construction and the elaboration of a planned design of the city, that recognised important social organisational criteria such as hierarchical social strata and symbolic divisions into halves- upper and lower, right and left…Supe society produced advanced scientific and technological knowledge; it constructed the first planned cities in the New World and laid down the foundations of what would become the Central Andean social system.[41]

Leaving aside the question of the evidence for accurate astronomical and calendrical alignments, which she does not provide, her argument depends on a self-evident understanding of knowledge and space. If a set of structures has a spatial ordering then there must have been a planner or group of planners. The apparent differentiation in the quality of domestic spaces may be evidence of social division, but it may also be interpreted as permanent and occasional accommodation. However, the claim of necessary hierarchy looks less cogent if the large geometric and spatially organised structures in the Amazon were built communally without an expert elite. Other archaeologists such as Richard Burger suggest that it was possible to mobilize the large labor force needed for such monumental architecture without state coercion. Like Shady he thinks religious ideology was the key innovation:

In motivating collective efforts, maintaining order and perpetuating the system… an ideology that held that the community not the individual owned and controlled critical resources… structured many of the productive activities and shaped social and economic dimensions. Consequently it would be misleading to think of religion – and particularly in these early ‘ceremonial centres’ – as somehow separate from the economic or political spheres.[42]

For Burger, unlike Shady, hierarchy is not self-evidently necessary nor is communal ideology inherently coercive.

Herrera proposes a ‘heterarchical framework that drives socio-spatial organization’ and: sketch[es] a picture of Andean social complexity as embedded in the history of deeply intertwined sacred and economic landscapes, held together by reciprocal relations about places, including sources of water, ultimately anchored in memory through the idiom of kinship.[43]

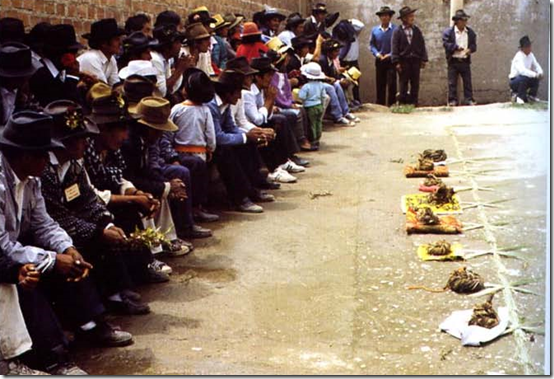

Burger’s and Herrera’s interpretive frameworks differ from that of Shady and Haas, not only in conceiving knowledge and space as an emergent effect of heterarchy, but also in being performative rather than representational, a framework which brings to the fore two key dimensions. The first gives the community active and engaged agency rather than reducing them to passivity and coercion. The second is the manifest spatial character of all the Norte Chico sites and especially Caral, where the central and most obvious characteristic is not the buildings or their layout, but the plazas and their associated performance spaces, spaces where the community enact their understandings of the world and the cosmos.[44] The cultural landscape and the community are the product of movement and social interaction, of people making connections. However, the performative and emergent character of an heterarchical, distributive system, framework cannot be assumed presumptively, it has to be held in tension with the top down structuralist character of an hierarchical one. But I also think we should treat the notion of tension as having more ontological significance than this epistemological point would suggest.

These reasons lie in the role of string and stories, textiles, khipu and narratives; other forms of connection which seem relatively slight, mundane and banal against the massive solidity of the pyramids and the vast plazas, but which were also central to the performance of knowledge and space at Caral.

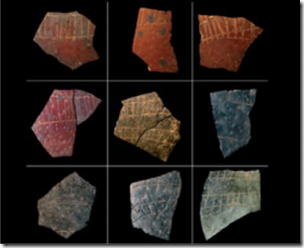

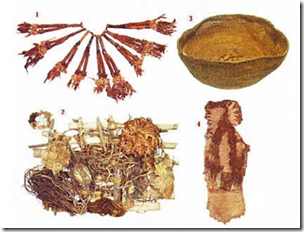

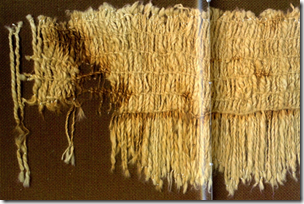

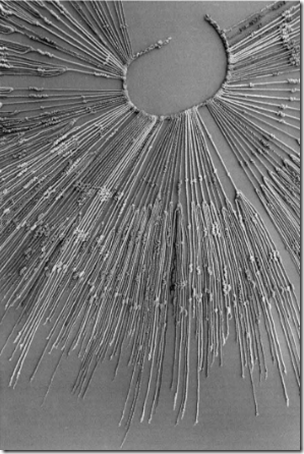

In a sealed room in one of the pyramids in 2005 Shady and her team made the most exciting find at Caral – the earliest known example of a khipu, a proto-khipu consisting of a ladder-like assemblage of 12 cotton strings, some knotted, wrapped around sticks. Famously Khipu are the knotted string devices used for recoding and transmitting information in the Inca Empire. Along with the khipu many fragments of textiles have been which along with the landscape itself are held to be readable as narratives of social order and identity.

Heather Lechtman in her brilliant analysis of Andean technologies of power argues that solutions to the problem of productive management of the disparate and distributed systems in the Andes that were ‘uncoordinated spatially and temporally’, ‘had to be solutions of articulation, design and labour orchestration rather than through tools, artefacts, or machines’.[45] And it was textiles, string and Khipu that provided the means of orchestration.‘Textiles were the primary visual medium for the expression of ideas, the fundamental art form of the Andean peoples’.[46] Their ‘weaving insists that messages be embodied in and expressed by structure’. [47] As Katherine Seibold puts it, ‘Textiles are art which reveals cosmologies.’[48] Inca landscapes were draped with textiles, as for example on the island of the sun in Lake Titicaca, and people’s clothing was designed to be read t reveal their status and their ethnicity.

‘Andean solutions to the most fundamental, physical and mechanical problems of daily life, as well as those of communication and ideology, were sought, conceived and executed through resource to technologies based on the engineering of fibres.’[49] According to William Conklin ‘tension was the Inca way. Textiles are held together by tension and they exploited that tension with amazing inventiveness and precision’.[50]

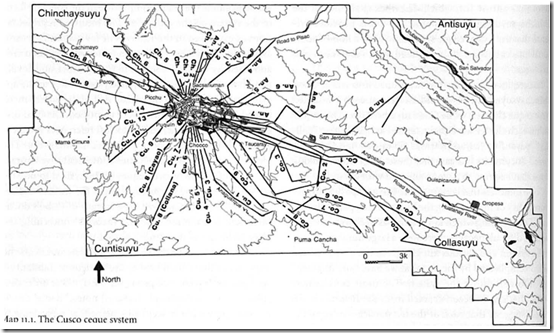

Likewise the landscape was marked by lines (ceques) radiating out from the capital Cuzco. These lines joining sacred shrines (huacas) formed an abstract social map projected onto the landscape as paths, which had their fabric and material analog in the knotted string khipu.[51] In their ‘discursive construction of the landscape…the ceque lines, and the khipu may be homologous forms: visible, tactile, and emotive, they each embody knowledge, produce history, and harness the memory’. [52] Khipu are knotted strings that hang off a main primary cord. Their spin, colour, size of knots and so on can record all kinds of knowledge. It has been known for some time that some of them are numerical ledger books recording llama flock numbers, labour tax records, tributes and food quantities in storage.[53] It is now hypothesised that there are many varieties of khipu and some may also encode narratives and histories.[54]

This understanding fits with that of the anthropologist Frank Salomon who has recently found khipus are still in use in some Peruvian villages.[55] Admittedly they have been undoubtedly transformed from those of their original Inca ancestors, nonetheless he finds khipu are markers of social obligation to the commons, and are also badges of office. They are used in pairs in dialogue with each other; one as sort of simulation of an agenda, the other a simulation of the results. The dialogue between the plan and the record generates the communally agreed rationality of the community and public acknowledgement of the labour obligations of its members. Basically Salomon finds khipu to be operational devices for trying out alternatives, for modelling and assembling a plan for the commons through being publicly performed in theatres or ceremonial plazas.

In Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years, Elizabeth Barber made a delightful observation that she suspects string to be ‘the unseen weapon that allowed the human race to conquer the earth, that enabled us to move out into every econiche on the globe during the Upper Palaeolithic. We could call it the String Revolution’.[56] The recognition that the capacity to join things together through lashing, binding and knotting, with string or cordage, is what enabled people to move is of profound importance. Movements are performed by groups of people through the actions of their own bodies and are coordinated and motivated through ritual, music, dance and stories. Historically stories and string were very likely coproduced with one another; they certainly inform each other mythopoetically through the fundamental commonality of narrative and weaving. Weaving and storytelling reflect a common origin in the derivation of text and textile from the Latin verb texere to weave. What weaving, stories, and string share is the complex duality of tension and connection, difference and similarity. Stories join ideas, string joins things together, and both are dependent on tension.[57] String and cordage derive their connective capacity from tension in knots, binding, or twining. Weaving depends on the tension between the warp and the weft.

The “incredible fact,” in the view of William J. Conklin, architect, archaeologist and research associate at the Textile Museum in Washington, D.C, is that “weaving was invented for what we might call ‘conceptual art’—to communicate meaning—and only afterward was it used for clothing. Textiles are important to every society. But their role in Andean societies as carriers of meaning and power is different from anything else that I know.”[58]

Just as khipu are not forms of writing Andean textiles are not representations.[59] Weaving and textiles like khipu are profoundly tactile coming alive in performance, which makes Andean knowledge traditions profoundly different ontologically and epistemologically from those underpinning Western conceptions of modernity. For the Inca ‘[t]he universe and the world are alive and this can be captured in weaving, the threads can have power, life and meaning are imparted by the weaver through rotation spinning and twisting’.[60] Tension is thus central to an Andean ontology, and to heterarchy and complex adaptive systems in the opposition of positive and negative feed back.[61] But, tension is also central to the agonistic pluralism and diversality that is vital to working with differing knowledge traditions, and to the possibility of emergent new knowledge.

Just as khipu are not forms of writing Andean textiles are not representations.[59] Weaving and textiles like khipu are profoundly tactile coming alive in performance, which makes Andean knowledge traditions profoundly different ontologically and epistemologically from those underpinning Western conceptions of modernity. For the Inca ‘[t]he universe and the world are alive and this can be captured in weaving, the threads can have power, life and meaning are imparted by the weaver through rotation spinning and twisting’.[60] Tension is thus central to an Andean ontology, and to heterarchy and complex adaptive systems in the opposition of positive and negative feed back.[61] But, tension is also central to the agonistic pluralism and diversality that is vital to working with differing knowledge traditions, and to the possibility of emergent new knowledge.

The conditions for possibilities of there being other knowledges, other spaces, other rationalities’ lie, as Dussel suggested, in creating a space for transmodernity in which modernity and its negated alterity could co-realise themselves in a process of mutual creative fertilization. However, I would argue, along with Dussel, that in order to ground an anti-foundationalist position with its recognition of multiple incommensurable knowledge traditions you need to sustain critical reason in order to avoid the vitiation of simply celebrating difference.[62] Critical reason is best sustained through comparing the ways in which spatiality, temporality, knowledge and reason are coproduced in differing traditions. Such ontological dimensions are typically concealed and invisible behind a screen of self-evidence in any given tradition, bringing them to the fore and recognising them may best achieved through by putting them on a equitable footing, acknowledging that all knowledges whether they are indigenous, scientific or traditional, are local in that they are performed by people in places with specific practices. Holding them in tension can reveal the differing ways in which knowledge and space are co-produced. The linkings of people, practices and places and the production of knowledge spaces have messy, contingent, and only partly acknowledged dimensions: ontologies, systems of trust, reciprocity and obligation, technical devices, social strategies and spatial structures for moving, assembling, and performing the knowledge, along with narratives of spatiality and temporality that shape community and identity. In addition to being profoundly narratological and spatial, knowledges are also performative, they are based in embodied practices, in the movement of human bodies in engagement with each other, with the physical environment, and with their own artifacts, in the movement along cognitive trails through conceptual space in making linkages and connections.[63]

To make all these dimensions visible, to enable them to interact and to create the conditions for the possibility of the emergent knowledge, we need to experiment with ways to create third spaces, theatres of diversity in which differing knowledge traditions can not only be performed together, but can be critically compared in determining how best to proceed in sustaining diversity and the commons once we are aware of how things could be other than they are.[64] To that end I am working with Wade Chambers to develop Story Weaver at The Institute of American Indian Art (IAIA) and with Robin Boast at the Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology in Cambridge and Ramesh Srinivasen at UCLA to develop a distributed knowledge system between museums. Both these projects sustain the commons by allowing differing knowledges to work together while holding them in tension rather than absorbing them into one dominant tradition, but that is a story for another day.

This paper was previously subtitled ‘Other Spaces, Other Rationalities: Heterarchy, Complexity and Tension, Norte Chico, Amazonia and Narratives of Prehistory in South America’. It was delivered at the Institute of Postcolonial Studies, Melbourne on 5 Nov 2011 as part of the Southern Perspectives series by David Turnbull from the Victoria Eco-Innovation Lab (VEIL), Architecture Faculty, University of Melbourne (email gt@unimelb.edu.au).

[1] Turnbull, David. 2009. Introduction. Futures: Special Issue on The Futures of Indigenous Knowledges, Guest Editor David Turnbull 41 (1):1-5.

———. Working with Incommensurable Knowledge Traditions: Assemblage, Diversity, Emergent Knowledge, Narrativity, Performativity, Mobility and Synergy 2009. Available from http://thoughtmesh.net/publish/279.php?space#conclusionassemblage.Castro-Gomez, Santiago. 2008. (Post)coloniality for Dummies: Latin American Prespectives on Modernity, Coloniality, and the Geopolitics of Knowledge. In Coloniality at Large: Latin America and the Postcolonial Debate, edited by M. Moraña, E. Dussel and C. Jauregui, 259-285. Durham NC: Duke University.Santos, Boaventura de Sousa, Joao Arriscado Nunes, and Mari Paula Meneses. 2007. Introduction: Opening up the Canon of Knowledge and Recognition of Difference. In Another Knowledge is Possible: Beyond Northern Epistemologies, edited by B. d. S. Santos, xvix-lxii. London: Verso. Canaparo, Claudio. 2009. Geo-epistemology: Latin America and the Location of Knowledge. Oxford: Peter Lang.

[2] Pierre Bourdieu defines méconnaissance as self seeking silence, and for Dussel violent misrecognition is definitional of our encounter with the other.

[3] Diamond, Jared. 1997. Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Society. London: Jonathon Cape.

———. 2005. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive. London: Allen Lane.

[4] Especially the stories ‘Of exactitude in science’ 1935, ‘Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge’ 1942, ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ 1941

[5] O’Gorman, Edmundo. 1961. The Invention of America: An Inquiry into the Historical Nature of the New World and the Meaning of its History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

[6] Escobar, Arturo. 2008. Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes. Durham: Duke University Press. See also

[7] Mignolo, Walter. 1995. The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality and Colonization. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

[8] Dussel, Enrique. 1993. Eurocentrism and Modernity. boundary 2 2 (20/3):65-76.

[9] Viveiros De Castro, Eduardo 2004. The Transformation of Objects into Subjects in Amerindian Ontologies Common Knowledge 10 (3):463-.

[10] Mignolo, Walter. 2003. Globalization and the Geopolitics of Knowledge: The Role of the Humanities in the Corporate University. Nepantla: Views from South 4 (1):97-119.

[11] Cresswell, Tim. 2006. On The Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. New York: Routledge.

[12] Turnbull, David. 2004. Narrative Traditions of Space, Time and Trust in Court: Terra Nullius, ‘wandering’, The Yorta Yorta Native Title Claim, and The Hindmarsh Island Bridge Controversy. In Expertise in Regulation and Law, edited by G. Edmond, 166-183. Aldershot: Ashgate.

[13] Dunbar, Robin. 2007. The Social Brain and the Cultural Explosion of the Human Revolution. In Rethinking the Human Revolution: New Behavioural and Biological Perspectives on the Origin and Dispersal of Modern Humans, edited by P. Mellars, K. Boyle, O. Bar-Yosef and C. Stringer, 91-98. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

[14] Marwick, Ben. 2003. Pleistocene Exchange Networks as Evidence for the Evolution of Language Cambridge Archaeological Journal 13 (1):67-81.

[15] Dunbar, Robin. 2008. Kinship in Biological Perspective. In Early Human Kinship: From Sex to Social Reproduction, edited by N. Allen, H. Callan, R. Dunbar and W. James, 131-150. Oxford: Blackwell. Fiedel, Stuart, and David Anthony. 2003. Deerslayers, Pathfinders and Icemen: Origins of the European Neolithic As Seen from the Frontier. In Colonization of Unfamiliar Landscapes: The Archaeology of Adaptation, edited by M. Rockman and J. Steele, 144-168. London: Routledge.

[18] McBrearty, Sally. 2007. Down with the Revolution. In Rethinking the Human Revolution: New Behavioural and Biological Perspectives on the Origin and Dispersal of Modern Humans, edited by P. Mellars, K. Boyle, O. Bar-Yosef and C. Stringer, 133-151. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Henshilwood, CS, F d’Errico, et al. (2011) A 100,000-Year-Old Ochre-Processing Workshop at Blombos Cave, South Africa, Science, 334: 219-222.

[19] Balter, M (2011) First Buildings May Have Been Community Centers, Science Now.

[20] Erlandson, JM, MH Graham, et al. (2007) The Kelp Highway Hypothesis: Marine Ecology, the Coastal Migration Theory, and the

Peopling of the Americas, Journal of Island & Coastal Archaeology, 2: 161-74.

[21] Moseley, Michael, and Robert Feldman. 1988. Fishing, Farming, and the Foundations of Andean Civilisation. In The Archaeology of Prehistoric Coastlines, edited by G. Bailey and J. Parkington, 125-134. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moseley, Michael E. 2010. The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization: An Evolving Hypothesis. In the Hall of Maat Submitted August 10, 2004 for Peru y El Mar: 12000 anos del historia del pescaria. Pedro Trillo, Editor. Sociedad Nacional de Pesqueria. Lima, Peru, 2005. Caral Civilization Peru Weblog: The Origins of Civilization in Peru

Proyecto Especial Arqueológico Caral-Supe/INC 2005 [cited May 13 2010].

[22] Mann, Charles C. 2005. Oldest Civilization in the Americas Revealed. Science 307 (5706):34-35.

[23] Shady, Ruth, Jonathon Haas, and Winifred Creamer. 2001. Dating Caral, A Preceramic Site in the Supe Valley on the Central Coast of Peru. Science 292 (5517):723-726.

[24] Miller, Kenneth. 2005. Showdown at the O.K. Caral. Discover Magazine

Solis, Ruth Shady. 2006. America’s First City? The Case of Late Archaic Caral. In Andean Archaeology 111: North and South, edited by W. Isbell and H. Silverman, 28-. New York: Springer.

[25] Denevan, William. 2001. Cultivated Landscapes of Native Amazonia and the Andes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Balée, William, and Clark Erickson. 2006. Time, Complexity, Historical Ecology. In Time and Complexity in Historical Ecology: Studies in the Neotropical Lowlands, edited by W. Balée and C. Erickson, 1-20. New York: Columbia University Press. Erickson, Clark. 2003. Historical Ecology and Future Explanations. In Amazonian Dark Earths: Origins, Properties, Management, edited by J. Lehmann, D. Kern, B. Glaser and W. Woods, 455-500. Dordrecht: Kluwer. Erikson, Clark. 2003. Pre-Columbian Roads of the Amazon. Expedition 43 (2):21-30. Heckenberger, Michael. 2005. The Ecology of Power: Culture, Place and Personhood in the Southern Amazon, A.D. 1000-2000. New York: Routledge. Heckenberger, Michael. 2006. History, Ecology, and Alerity: Visualising Polity in Ancient Amazonia. In Time and Complexity in Historical Ecology: Studies in the Neotropical Lowlands, edited by W. Balée and C. Erickson, 311-340. New York: Columbia University Press. Heckenberger, Michael, Afukaka Kulkuro, Urissapa Kulkuro, Christian Russell, Morgan Schmidt, Carlos Fausto, and Bruna Franchetto. 2003. Amazonia 1492: Pristine Forest or Cultural Parkland? Science 301:1710-1715. Heckenberger, Michael, Christian Russell, Carlos Fausto, Joshua Toney, Morgan Schmidt, Edithe Pereira, Bruna Franchetto, and Afukaka Kulkuro. 2010. Pre-Columbian Urbanism, Anthropogenic Landscapes, and the Future of the Amazon. Science 321:1214-1217. Heckenberger, Michael J, Christian Russell, Joshua R Toney, and Morgan J Schmidt. 2007. The legacy of cultural landscapes in the Brazilian Amazon: implications for biodiversity. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 362 (148):197-208.

[26] Erickson, Clark. 2003. Historical Ecology and Future Explanations. In Amazonian Dark Earths: Origins, Properties, Management, edited by J. Lehmann, D. Kern, B. Glaser and W. Woods. Dordrecht: Kluwer

[27] Parssinen, Martti, Denise Schaan, and Alceu Ranzi. 2009. Pre-Columbian geometric earthworks in the upper Puru ́s: a complex society in western Amazonia. Antiquity 83 (322):1084-1095.

[28] Roosevelt, Anna. 1999. The Development of Prehistoric Complex Societies: Amazonia, A Tropical Forest. Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 9 (1):13-33. Heckenberger, Michael, Christian Russell, Carlos Fausto, Joshua Toney, Morgan Schmidt, Edithe Pereira, Bruna Franchetto, and Afukaka Kulkuro. 2010. Pre-Columbian Urbanism, Anthropogenic Landscapes, and the Future of the Amazon. Science 321:1214-1217. Mann, Charles. 2000. Earthmovers of the Amazon. Science 287 (5454):786-789

[29] cited in Mann 2000

[30] Turnbull 2000.

[31] Herrera, Alexander. 2007. Social Landscapes and Community Identity: the Social Organisation of Space in the North-central Andes. In Socialising Complexity: Structure, Interaction and Power in Archaeological Discourse, edited by S. Kohring and S. Wynne-Jones: Oxbow Books. Abercrombie, Thomas. 1998. Pathways of Memory and Power: Ethnography and History Among an Andean People. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

[32] Haas, Jonathan, and Winifred Creamer. 2006. Crucible of Andean Civilization: The Peruvian Coast from 3000 to 1800 BC. Current Anthropology 47 (5):745-775.

[33] Sandweiss, Daniel. Michael Moseley, 2001. Amplifying Importance of New Research in Peru. Science 294 (5547):1651-1653. Ghezzi, Ivan, and Clive Ruggles. 2007. Chankillo: A 2300-Year-Old Solar Observatory in Coastal Peru. Science 315 (5816):1239-1243.

Dillehay, Tom D., Jack Rossen, Thomas C. Andres, and David E. Williams. 2007. Preceramic Adoption of Peanut, Squash, and Cotton in Northern Peru. Science 316 (5833):1890-1893.

[34] Burger, Richard. 1992. Chavin and the Origins of Andean Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson, 32. See also http://www.chirije.com/the-spondylus-trail.html

[35] Brooks, Sarah Osgood. 1997. Source of Volcanic glass for Ancient Andean Tools. Nature 386 (6624):449-450.

Burger, Richard L., Karen L. Mohr Chávez, and Sergio J. Chávez. 2000. Through the Glass Darkly: Prehispanic Obsidian Procurement and Exchange in Southern Peru and Northern Bolivia. Journal of World Prehistory 14 (3):267-312.

Owen, Bruce. 2010. The Late Preceramic period: Massive Monuments in Simple Societies 2006 [cited June 1st 2010].

[36] Moseley, Michael. 2001. The Incas and Their Ancestors: The Archaeology of Peru. London: Thames and Hudson, 48-9.

Miller, Kenneth. 2005. Showdown at the O.K. Caral. Discover Magazine.

Salomon, Frank. 1987. A North Andean Status Trader Complex Under Inca Rule. Ethnohistory 43 (1):63-77.

Burger, Richard. 1992. Chavin and the Origins of Andean Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson.

Heyerdahl, Thor, Daniel Sandweiss, and Alfredo Narvaez. 1995. Pyramids of Tucume: The Quest for Peru’s Forgotten City. London: Thames and Hudson.

Sandweiss, Daniel H. 1999. The Return of the Native Symbol: Peru Picks Spondylus to Represent New Integration with Ecuador. Society for American Archaeology 17 (2).

Owen, Bruce. 2010. The Late Preceramic period: Massive Monuments in Simple Societies 2006 [cited June 1st 2010].

[37] Mann, Charles C. 2005. Oldest Civilization in the Americas Revealed. Science 307 (5706):34-35.

[38] Marwick, Ben. 2003. Pleistocene Exchange Networks as Evidence for the Evolution of Language Cambridge Archaeological Journal 13 (1):67-81.Gamble, Clive. 2007. Origins and Revolutions: Human Identity in Earliest Prehistory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[39] na. 2001. Ancient Peruvian Metropolis Predates Other Known Cities. National Geographic News

[40] Solis, Ruth Shady. 2006. America’s First City? The Case of Late Archaic Caral. In Andean Archaeology 111: North and South, edited by W. Isbell and H. Silverman, 28-. New York: Springer, 58-9.

[41] Op cit 36, 62.

[42] Burger, 38.

[43] Herrera, 180

[44] Moore, Jerry. 2005. Cultural Landscapes in the Ancient Andes: Archaeologies of Place. Gainesville: University of Florida.

[45] Lechtman, Heather. "Technologies of Power: The Andean Case." In Configurations of Power: Holistic Anthropology in Theory and Practice, edited by John Henderson and Patricia Netherly, 244-81. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993, 246.

[46] Ibid 255

[47] Ibid 273

[48] Seibold, Katherine. "Textiles and Cosmology in Choquecancha, Cuzco, Peru." In Andean Cosmologies through Time: Persistence and Emergence, edited by Robert Dover, Katherine Seibold and John McDowell, 166-201. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

[49] Lechtman, 255.

[50] Mann, Charles. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus. New York: Alfred Knopf, 2005, 83

[51] Abercrombie, 179

[52] Howard R, 2002, "Spinning A Yarn: Landscape, Memory, and Discourse Structure in Quechua Narratives", in Narrative Threads: Accounting and Recounting in Andean Khipu Eds J Quilter and G Urton (University of Texs Press, Austin) pp 26-52, 46. Frame M, 2001, "Beyond The Image: The Dimensions of Pattern in Ancient Andean Textiles", in Abstraction: The Amerindian Paradigm Ed C Paternosto (Societe des Expositions du Palais des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelle, Brussells) pp 113-136.

[53] Urton, Gary. Signs of the Inka Khipu: Binary Coding in the Andean Knotted-String Records. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003.

[54] anon. "Language Could Be Tied up in Inca Knots." Canberra Times, Aug 13th 2005, 15.Brokaw, Galen. "Toward Deciphering the Khipu." Journal of Interdisciplinary History xxxv, no. 4 (2005): 571-89.Conklin, Willliam. "A Khipu Information String Theory." In Narrative Threads: Accounting and Recounting in Andean Khipu, edited by J. Quilter and G. Urton, 53-86. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002.Quilter, J., and G. Urton, eds. Narrative Threads: Accounting and Recounting in Andean Khipu. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002.

[55] Salomon, Frank. The Cord Keepers: Khipus and Cultural Life in a Peruvian Village. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2004. See his khipu conservation project www.ucl.ac.uk/…/ peters-khipus/index.htm

[56] Barber, Elizabeth. Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years. New York: W.W, 45. See also Good, I. 2001, Archaeological Textiles: A Review of Current Research, Annual Review of Anthropology, 30, 209-226, 209.

[57] According to Webster’s Dictionary tension owes its etymology to the Sanskrit word for string. My thanks to Lesley Green for this point.

[58] Mann, Charles. 2005. Unraveling Khipu’s Secrets. Science 309 (5737):1008-1009.

[59] Mignolo, Walter. 1995. The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality and Colonization. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 86.

Boone, Elizabeth Hill. 1994. Introduction: Writing and Recording Knowledge. In Writing Without Words: Alternative Literacies in Mesoamerica and the Andes, edited by E. H. Boone and W. Mignolo, 3-26. Durham: Duke University Press.

[60] Conklin, William. 2008. The Culture of Chavin Textiles. In Chavin: Art, Architecture, and Culture, edited by W. Conklin and J. Quilter, 261-278. Los Angeles: Costen Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

[61] Turnbull, David. Working with Incommensurable Knowledge Traditions: Assemblage, Diversity, Emergent Knowledge, Narrativity, Performativity, Mobility and Synergy 2009 [cited. Available from http://thoughtmesh.net/publish/279.php?space#conclusionassemblage.

[62] Dussel, Enrique. 2000. Epilogue. In Thinking from the Underside of History: Enrique Dussel’s Philosophy of Liberation, edited by L. Alcoff and E. Mendieta, 269-290. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 276-7.Turnbull, David. 2005. Multiplicity, Criticism and Knowing What to Do Next: Way-finding in a Transmodern World’. Response to Meera Nanda’s Prophets Facing Backwards. Social Epistemology 19 (1):19-32.

[63] Cussins, Adrian. 1992. Content, Embodiment and Objectivity: The Theory of Cognitive Trails. Mind 101:651-688.

[64] Guardiola-Rivera, Oscar. 2010. What If Latin America Ruled the World? How the South Will Take the North into the 22nd Century. London: Bloomsbury Press, 48.

Escobar, Arturo. 2008. Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes. Durham: Duke University Press, 25.