News from Senegal about the latest Biennale, featuring ‘Producing the common’ that allows for anonymous contributions from artists. Many new possibilities are opened.

The Dakar Biennale 2014 by Olga Speakes Anna Stielau on 20 June | Artthrob.

News from Senegal about the latest Biennale, featuring ‘Producing the common’ that allows for anonymous contributions from artists. Many new possibilities are opened.

The Dakar Biennale 2014 by Olga Speakes Anna Stielau on 20 June | Artthrob.

Kay Abude, Piecework, 2014 Steel, MDF, timber, plywood, fluorescent lights, chairs, cardboard, paper, plaster, silicone rubber, paint, brushes, various modeling tools and steel utensils, latex gloves, cotton and nylon rags, cotton velvet, silk, rayon braided cord and workers. Dimensions variable

Piecework, 2014 is an installation and series of durational performances that occur throughout its exhibition in Gallery 2 at Linden Centre for Contemporary Arts. The installation consists of three workstations and three workers dressed in a uniform. The workers engage in an activity of casting plaster objects from moulds in the form of 14.4kg gold bars. These casts are then painted gold. Piecework displays a purposefully futile labour of a repetitive and tireless fashion. It explores a form of work relating directly to performance that is quantifiable, investigating ideas of power and value and asks questions about the role and meaning of labour within artistic practice.

Shift work is characteristic of the manufacturing industry, and the artwork employs performative strategies in a rigorous process and task orientated manner by using Linden as a workplace that is in constant operation over the period of a 24-hour cycle. The ‘three-shift system’ is performed (Shift 1: 06:00-14:00, Shift 2:14:00-22:00 and Shift 3: 22:00-06:00) by the three workers who produce these gold bars throughout the six week exhibition period. The workers are paid a fixed piece rate for each unit produced/each operational step completed per shift. Ideas of the factory are embedded in the vary nature of the work mimicking a manufacturing process carried out by uniformed workers who take up their posts in eight hour shifts.

The catalogue essay by Jessica O’Brien:

The poetry and politics of production

Addressing the intersection between art, life and capitalism, Kay Abude’s Piecework interweaves personal experience, a critique on the distribution of global economic power, and the relationship between producers and consumers.

Piecework unfolds over a six-week period. A durational performance piece highlighting labour and process, the performers undertake manufacturing processes that reference the artist’s personal experience and recent site visits to Chinese factories. The group works through an endless pattern of standardised procedures that result in gold painted serialized plaster ingots. The performances are structured according to a three-shift system, dividing the day into three eight-hour working shifts that mimic a continuous 24-hour production cycle.

By foregrounding the body of the worker, Piecework engages with the pervasive neo-colonial first world practice of exploiting emerging economies and their abundance of cheap, unregulated labour. With most of Australia’s goods produced offshore, the performance addresses the disconnection in the minds of the consumer between the products we buy, and the often dehumanising labour that is required to produce it.

Banal, repetitive, precise and designed for maximum efficiency, Piecework could stand in for the processes behind countless products and could be extrapolated in factories a hundred or a thousand times over. Each action is carefully considered, creating a Haiku-like poetry to the work.

Highlighting the formality existing in standardised production, there is a purposeful ambiguity in the artist’s aestheticised interpretation of reality. Kay writes: “Two different types of labour exist in the two environments of the factory and the studio. The large populations filling the factories are dependent on the market that exploits them. These people labour because they must work for their livelihoods – they work in order to live and survive. The labour present in art practice is one that is voluntary and pleasurable for the artist – the artist lives to work and create.”[1]

Downplaying the desire for a single ‘artist’s hand’ in the work, while expressly displaying the labour that it took to create it, the audience is left to question the value of the objects that are produced, and how it is conferred.

At the crux of these ambiguities is the role of the audience in the artwork. “The fine arts traditionally demand for their appreciation physically passive observers…but active art requires that creation and realization, artwork and appreciator, artwork and life be inseparable.”[2] Utilising the understanding that the relationship between the artist and the audience is at the heart of Performance Art, the seemingly passive and non-participatory viewers of Piecework are in fact directly implicated in the work.

Piecework replicates the role the audience plays as participants of consumer culture, in their role as consumers of the artwork. Abude is the manufacturer and we the consumer. Without a market or an audience, ‘production’, in every sense of the word, would not exist.

By foregrounding the human process by which consumer goods are made through the physical presence of the workers, Piecework addresses the disconnection and compartmentalisation that is characteristic of present day consumption in a capitalistic society. And yet it also replicates those very relationships, distilling and aestheticising disturbing imbalances of power.

As Claire Bishop’s remarks: “The most striking projects… [hold] artistic and social critiques in tension.”[3] Piecework is a considered response to a pervasive social issue, but does not attempt to present a fixed meaning, or take on the herculean responsibility of suggesting a solution to global economic inequality. As unwitting participants of the performance, the significance we chose to ascribe to our role as a consumer of product and artwork is up to us.

Jessica O’Brien

June 2014

Jessica O’Brien is an independent curator and writer based in Melbourne.

[1] Abude, Kay, Put to work, M Fine Art, Faculty of the Victorian College of the Arts and Music, The University of Melbourne: November 2010, p. 28.

[2] Kaprow, Allen, Essays in the Blurring of Art and Life, Berkeley: University of California Press: 2003, p. 64.

[3]Bishop, Claire, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, Verso Books: 2012, p. 277-8.

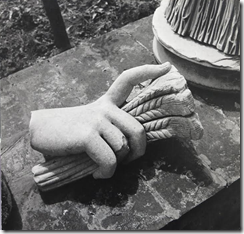

Therese Keogh was invited to create work for the Sievers Project, an exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Photography that revisited the work of a major Australian photographer who documented the glories of industry in the 20th century. Keogh was drawn to Sievers’ photograph of a severed hand holding a sheaf of wheat, a fragment of the marble statue of Ceres in Rome. She discovered that much of the imperial marble was eventually transformed into quicklime used to make concrete. It can also be used as a soil amendment to counterbalance soil acidity. In order to investigate this process herself, Keogh sourced a marble pediment of an altar from a church in Ballarat. She then worked out how to fire this marble, which was eventually displayed in the gallery as a block of quicklime.

Therese Keogh was invited to create work for the Sievers Project, an exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Photography that revisited the work of a major Australian photographer who documented the glories of industry in the 20th century. Keogh was drawn to Sievers’ photograph of a severed hand holding a sheaf of wheat, a fragment of the marble statue of Ceres in Rome. She discovered that much of the imperial marble was eventually transformed into quicklime used to make concrete. It can also be used as a soil amendment to counterbalance soil acidity. In order to investigate this process herself, Keogh sourced a marble pediment of an altar from a church in Ballarat. She then worked out how to fire this marble, which was eventually displayed in the gallery as a block of quicklime.

Keogh’s work witnesses the reduction of art into commerce. This can be seen as a loss echoing the demise of the grand paternalistic world of manufacture once celebrated by Sievers. But it can also be seen as a recovery of value from what is left behind, returning products of human endeavour to the earth from whence it came.

What is interesting from the perspective of South Ways is the adventure of the artist in confronting the material challenge herself, without recourse to external assistance. Her two hands thus provide a tangible link between the various phases of the cycle, moving from monument to earth. They allow us to witness the transformation of matter itself, a dimension otherwise absent from the silvery surfaces of Sievers’ prints.

Below are photos of the firing of the marble with Keogh’s description of the process:

These images show the firing of a marble object inside a large steel box. I started with a block of marble in my studio, and – over a period of several months – chipped away at its surface. I didn’t begin this process with an end point in mind. Part of me was looking for a fault in the marble, and so I kept carving in the hope that the stone would reveal its weaknesses, which would then allow me to stop. But one day the mallet I had been using broke with the force and repetition of the carving. The mallet’s head split in two, and it was like the marble was reacting against its own transformation. So I stopped.

Marble is a form of calcium carbonate, metamorphosed from limestone. When fired, the carbon dioxide trapped inside is burned away, transforming the calcium carbonate into calcium oxide, or quicklime. Quicklime doesn’t occur without human intervention, and is used for a variety of applications (including as a base ingredient in concrete, and, in agriculture, as a soil amendment to neutralise earth with high acidity). It is called quicklime (from the original meaning of the word ‘quick’ as something that is alive, or living) because when it comes into contact with water a chemical reaction takes place that creates extremely high temperatures, and has been known to cause severe burns to the skin of people working with it.

Once the carving had finished, I constructed a steel box that would house the marble during its firing. The box protected the marble from the smoke of the fire, and allowed it to be heated more evenly.

My mum owns a property in Central Victoria, where I took the marble and the box to be fired. I propped up the box, with the marble inside, on four bricks in a paddock, and built a fire around it. The fire burned for about eighteen hours, as I stoked it through the night. When it had died down, I took the lid off the box. The marble – now quicklime – had cracked as it heated and cooled. Its surface had changed from being luminous to kind of chalky, as its chemical composition was irreversibly altered from the fire.

Therese Keogh, After Firing (CaO), image courtesy Christian Capurro, 2014

Therese Keogh is a Melbourne artist – www.theresekeogh.com. Featured image at the top of this page is her hand-drawn version of the original Sievers’ photo.