In a recent article for Thesis Eleven, Nikos Papastergiadis argues that “the idea of the Global South is now over.” From the optimism of Bandung, he traces a growing complex and critical understanding of “uneven development”. As an art theorist, his focus is particularly on its identity in global events such as Documenta. His analysis of Okwi Enwezor’s Documenta XI and Decolonial AestheSis is illuminating, but his overall scepticism about the South as a framework is not as productive.

Of course, any overarching concept leads inevitably to homogenisation, which must be resisted critically. This critique can be useful if it leads to a more responsive framework, rather than a disavowal of the political arena.

The problem with Papastergiadis’ writing is that it returns inevitably to the personal. A reader would be forgiven for expecting some alternative framework or concept emerging from this critique. Instead, we have “a couple of stories about the South and narrate the difficult relationship between art and politics from a more personal perspective”. The two anecdotes are incidental exchanges regarding personal trust between participants in global forums.

In the Santiago gathering of the South Project, the South African curator Kwesi Gule spoke about the “lucky turkeys” who attend such events. He referred to the practice of sparing a turkey before the annual bird sacrifice of Thanksgiving, drawing a parallel with the fortunate exceptions of disenfranchisement that are lucky to attend such global gatherings. I don’t think this should stop us meeting, as the face to face live argument is so important for generating the kind of revelations that Gule made. But we should always be critically reflexive of our own position in speaking for others.

While such gatherings favour the bold unmasking of illusions such as the Global South, they don’t always take cognisance of the role these frameworks can play in sustaining hope and solidarity outside the seminar room.

Hardt and Negri show an awareness of this in their support for a pre-postmodern concept of truth:

The postmodernist epistemological challenge to ‘the Enlightenment’ — its attack on master narratives and its critique of truth — also loses its liberatory aura when transposed outside the elite intellectual strata of Europe and North America. Consider, for example, civil war in El Salvador, or the similar institutions that have been established in the post-dictatorial and post-authoritarian regimes of Latin America and South Africa. In the context of state terror and mystification, clinging to the primacy of the concept of truth can be a powerful and necessary form of resistance.

(Michael Hardt & Antonio Negri Empire Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001, p. 155)

Papastergiadis’ language is threaded with poetic phrases. He describes how “a new kind of `cartography’ is woven into existence: one that is constituted through the choreographic manoeuvres that interweave motion and mooring.” While enchanting to read, and particularly to hear, such a expressions rarely provide a proposition for thinking.

If someone is going to claim the “end of the South”, they should provide an alternative that can respond to the need for solidarity and understanding between peoples and their communities.

Perhaps instead, we can look at an end to the South in a purely academic sense, and seek instead for forms of action that can further the kinds of relationships that the idea of South inspires.

Postscript

Papastergiadis, Nikos. 2017. “The End of the Global South and the Cultures of the South.” Thesis Eleven, June,

Raewyn Connell continues to provide for an engaged version of “southern theory” in her work with unions, gender activism and development of workshops. Bruno Latour’s Reset Modernity project is also an exemplary model of how academic practice can seek broader engagement.

Platforms for a more pragmatic use of the South can be found in South Ways and Joyaviva.

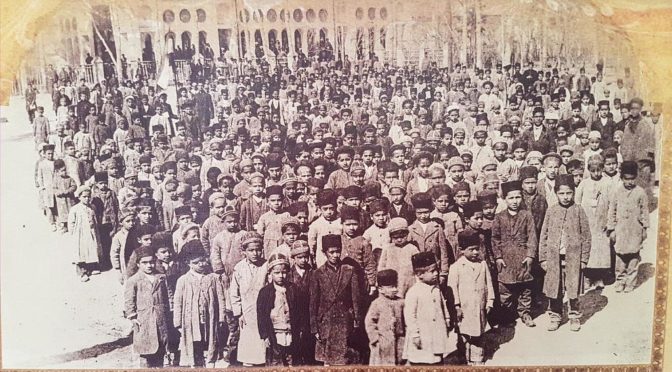

Image is from the Museum of the Constitutional Revolution, Isfahan, Iran