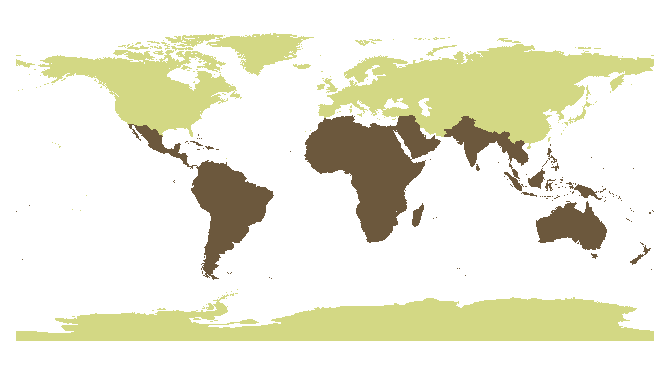

The essay circulates among colleagues and centers of the newly created Latin American network of critical southern thinking, in order to discuss the territorial, political and epistemological status of the “global South”

Sur El objetivo de estas breves notas es proponer una discusión acerca del estatus epistemológico y político del Sur. Se trata de pensar al Sur en el doble sentido de la producción de conocimiento social situado en regiones “periféricas” de la globalización, y de una reflexión sobre el espacio que -habiendo sido denominado antes como tercer mundo, países sub-desarrollados o en vias de desarrollo, postcolonia- hoy es definido como “Sur Global”. Si en cuanto a lo territorial la definicion del “Sur” es sumamente imprecisa, puede pensarse en definirlo en torno a la materialidad de la experiencia y de un pensamiento autoctono sobre esta? La cuestión epistemológica va de la mano de la discusión geopolítica y económica: dónde esta situado y que regiones incluye el Sur Global?

Mientras Latinoamérica y Africa parecen no presentar dudas acerca su pertenencia, cómo debe considerarse a India, país de grandes proporciones económicas y poblacionales, o de que manera evlauar el dilma que presenta China, nueva super potencia mundial, segunda economía del planeta, y que constituye un eje central ineludible de todo debate sobre el significado y extension del Sur global. Cuál es el lugar y rol del Este, de Asia, en el Sur, entendido como categoria política-económica? Cuál es el rol de las nuevas potencias emergentes, o BRICS, como es el caso de Brasil, dentro de la condición latinoamericana? Constituyen los BRICS un nuevo actor central dentro de los bloques de dominacion globales? o son mas bien la vanguardia del Sur, en tanto potencias políticas y económicas que marcan el rumbo en sus respectivas regiones y actúan de modo articulado en foros globales de relaciones internacionales o con relación a organismos multilaterales de fnanciamiento?

De modo similar, es preciso debatir el estatus político de Rusia en tanto perteneciente al Sur, lo cual abriría un debate sobre la condición “Sur” de Europa del Este. La situación contemporánea del ex bloque soviético propone un debate acerca de si la “globalización” es una categoría militar, a la vez que política-económica, ya que solo fue posible comenzar a hablar de un mundo global hacia el fin de la Guerra Fría, en el principio de la década de los noventa cuando un bloque sometió militar y económicamente al bloque enemigo. Fue precisamente en los campos de guerra “calientes” del Sur global, campos de invasión, control y contrainsurgencia, donde se peleó en concreto la abstracción diplomática de la Guerra Fría. Esta condición necesariamente marcó a fuego las transiciones democráticas de los noventa en el Sur, doblegadas por la herencia politica del totalitarismo y la crisis de la deuda externa. En verdad se puede considerar a la globalización también una categoria financiera, a partir de la hegemonia creciente del capital financiero que acompañó a esa victoria militar planetaria. De manera paralela al nuevo pensamiento de escala mundial, el Sur, o Sur Global, se consolidaron como categorías de análisis a partir de aquel comienzo del debate sobre un mundo globalizado.

La cuestión de pensar al Sur abre un debate acerca de la distribución política de espacios dentro de los hemisferios: en primer lugar, ironicamente, gran parte del “Sur” global se halla situado en el hemisferio norte; en segundo lugar, la categoría de “Sur” atraviesa distinciones anteriores entre oriente y occidente. La situación de Latinoamérica dentro del debate sobre el Sur también pone en cuestión la categoría misma de “Occidente”, en la cual actores políticos de distinto signo habían clásicamente colocado a la región. De qué manera un sub continente cultural, religiosa y politicamente “occidental”, puede agruparse dentro una misma categoría que engloba a Africa y Asia? De este modo, el debate abre la categoria de “Sur global” a distintas perspectivas. Evidentemente, este nombre realiza algún trabajo epistémico y político que ha tornado necesaria su aparición y consolidación. Pero se trata de una distinción epistemológica, geopolítica, espacial, tecnológica o económica? Se puede considerar una hipótesis que consiste en pensar al Sur a la vez como un territorio geográfico (el mundo “periférico” por fuera de los países centrales de EEUU y Europa occidental), así como también un espacio de relaciones económicas determinado por el endeudamiento, el desarrollo desigual y un modelo de acumulación fuertemente determinado por la inequidad y dominación establecida por el sistema capitalista mundial desde 1945.

El “Sur” constituye, más allá de espacios geográficos concretos, un haz de relaciones socio-económicas: el Sur como relación. Se trata de dinámicas que reproducen estrategias de poder global y que poseen nodos tanto en el “Norte” como en el “Sur”. Es preciso no pensar al Sur a nivel territorial, de espacio o escala, sino como forma-de-vida. Hay que explorar como la cuestión de las mediaciones entre campos que la modernidad ha presentado como disímiles o separados, se hallan entremezcladas de modo diferente, produciendo formas institucionales, de vida cotidiana y de subjetividad propias y singulares. El Sur puede ser conceptualizado como una serie de historias paralelas, comparables. Si se trata de un tipo de espacio, es un territorio sin fronteras definidas donde la Historia ha “tenido lugar” de modos similares, en cuanto a formaciones de poder, capital y subjetivación. El Sur presenta trayectorias intrconectadas de imperialismos políticos y económicos, colonialismos externos e internos, conformación e interrupción del estado-nación y despliegue de proyectos de lo nacional-popular.

De manera fundamental el Sur también ha sido moldeado por procesos de violencia política colonial y neo-colonial, de represión, partición territorial y conflicto interno que en gran medida han obedecido a esquemas trans-nacionales que han conectado a diversas regiones del mundo. El estudio de las transiciones democraticas en Latinoamerica en los ochenta ilumina procesos similares ocurridos luego en Africa. Las definiciones estatales de raza, etnicidad e indigeneidad derivadas del colonialismo y heredadas por los estados poscoloniales africanos y asiaticos son terreno fertil para repensar de manera diferente las estructuras sociales imperantes en America Latina. En la actualidad, el Sur se halla articulado como el territorio de la subsunción real por el capital; el espacio geográfico y económico que es objeto de una nueva ronda de acumulación primitiva del capital, que se lleva a cabo bajo el signo de la absolutización del capital extractivo y el capital financiero.

Efectivamente, las diversas regiones del Sur global pueden ser conectadas en un plano político y epistemológico comparativo que ilumina dinámicas locales a través de su reflejo en procesos similares. Se trata de analizar procesos de colonización de signo semejante y contemporáneos: por caso, no sólo las herencias del colonialismo español en América Latina, sino también el colonialismo británico semi-formal que rigió en la región desde mediados del siglo diecinueve, y que la coloca en estrecha relación historica y política con los estados postcoloniales de India y Africa, que también emergieron del mismo sistema de dominación y violencia, y asimismo con regiones como el medio oriente, donde la influencia política y diplomática británica fue rampante, hasta el caso de la formación del estado de Israel y el quiebre de Palestina. Hoy, el Sur global presenta herencias de estos proyectos en el sentido de que se puede englobar a estas regiones dentro de la categoría de espacios surgidos de procesos post-totalitarios.

El Sur esta conformado por regiones de experiencia post-Stalinista, como en la Europa del Este; regiones postcoloniales que han sido fuertemente marcadas por la violencia política de la dominación colonial europea, como en Africa y el Sur Asiático, regiones post-dictadura, como el Cono Sur latinoamericano y su experiencia de colonialismo semi formal diplomático y miltar estadounidense, que también se refleja en la condición de post-conflicto armado e intervención extranjera, como en la región Andina. Mecanismos neo-coloniales de alcance global, tales como los planes de ajuste estructural y el modelo de endeudamiento externo, así como las técnicas de contrainsurgencia de desaparición forzadas de personas, articulan diversas historias políticas, temporalidades económicas y espacios trans-regionales. En la actualidad, la dinámica del capitalismo de extracción, con sus métodos, agentes y efectos, que se repiten a través de regiones y sub-continentes, abre nuevos espacios para el trabajo epistemológico comparativo sur-sur.

Pensamiento Si el Sur es un conjunto de formas de vida singulares, en los últimos tiempos este espacio y esta vida ha ido generando un pensamiento propio sobre esas formas y texturas. En este sentido, resulta más preciso hablar de un pensar “al” Sur, y no “desde” el Sur. La frase “pensar al” implica a la vez el lugar de producción del teorizar y su objeto. La fórmula “desde el Sur” parace seguir respondiendo al motivo de un pensamiento que es generado para una audiencia privilegiada situada en otro sitio: en el “Norte”. En intersección con estos parámetros económicos y geopolíticos, se puede proponer pensar al “Sur” como un imaginario, una perspectiva epistémica engarzada en relaciones socio-económicas (entre regiones y también al interior de los estados-nación) y un modelo de desarrollo que generan una perspectiva diferencial en cuanto al pensamiento de lo social. Esta condición no es anecdótica o circunstancial: puede decirse que desde hace tiempo la teorización más avanzada acerca de lo social y sus crisis recientes ha sido generada en el “Sur”, ante el estancamiento evidente de gran parte del pensamiento generado en el Norte. La producción del conocimiento social generada en el sur posee diversas características, entre ellas una impronta muy particular, relacionada a su contexto socio-económico, y que la diferencia de lo producido en el Norte: la teorización social producida en el Sur es generada por académicos, intelectuales públicos y movimientos sociales y políticos, en estrecha relación con demandas de la esfera pública, lo político, y los medios de comunicación de distinto signo.

Este contexto de producción de saber, permeable a las fronteras difusas entre campos y géneros, y fuertemente sesgado por transformaciones políticas y económicas, coloca al pensamiento generado en el sur en un plano muy diferente de las teorizaciones producidas desde lo que resta de las aisladas torres de marfil de la academia del norte, o del saber experto de los centros de investigación privados. Pensando al Sur, examinando la producción reciente de conocimiento social a distintos niveles, puede plantearse que así como lo local produce inflexiones y tensiones que median y refractan lo global, modificándolo, de la misma manera el pensamiento al Sur produce una inflexión en lo que es el pensar en sí mismo. Esto significa ver al pensamiento al Sur como una perspectiva, un modo de enfocar el mundo de lo social, y expresado mas allá de nativismos o chauvinismos o el intento fútil de recobrar supuestas prístinas cosmogonías o pensamientos ancestrales. Otra característica crucial de la producción del conocimiento al Sur con respecto al Norte es que la misma no tiene lugar solo en ámbitos académicos, sino que los movimientos sociales de base actualmente teorizan sus propias prácticas de organización y acción, asi como también condiciones socio-económicas en sus regiones y el impacto sobre ellas de flujos globales de capital, tecnología e información.

El pensamiento al Sur se genera en un contexto social de producción que implica la mencionada práctica de los movimientos sociales; intelectuales públicos independientes de fuentes internacionales de financiamiento, relacionados a sectores políticos o sociales o mediáticos; y una estructura universitaria que aún, con fuertes condicionamientos e influencias externas (sobre todo hoy del modelo estadounidense) posee formas de organización y estructuración que son particulares y propias, y que generan, en contacto con la demanda de lo social, formas trans-disciplinarias de trabajo intelectual. En este contexto, el pensamiento al sur genera sus propios marcos conceptuales. Se trata de descentrar dicotomías clásicas entre lo universal y lo particular, según las cuales, los parámetros de pensamiento generados en el norte o centro (antes Europa, hoy también Estados Unidos) constituían una guía general que luego se adapataba a “casos” regionales cuasi etnográficos y a historias locales. Es preciso, para sopesar la dimensión y la relevancia de las teorías producidas en el Sur, debatir el contexto actual institucional y de financiamiento de la producción de conocimiento social en el Sur.

Cuáles son los flujos de capital que posibilitan directa o indirectamente la teorización de lo social? Cómo es el campo de estrategias y luchas en torno a las decisiones de privilegiar determinadas áreas y objetos de investigación y pensamiento? Lejos de meramente adoptar y reproducir conceptos y categorías generadas en el norte, actualmente la producción social del conocimiento al sur retoma esas formas e ideas reelaborándolas absolutamente, traduciéndolas en versiones que las modifican, adaptadas a las cambiantes condiciones socio-económicas regionales. La globalización económica y del saber, con sus sucesivas crisis profundas, no ha generado una uniformización del conocimiento sino que ha puesto al alcance de productores locales y regionales de saber toda una serie de conocimientos y conceptos que antes no circulaban, y este proceso ha relativizado su hegemonía absoluta, posbilitado un bricolage que transfroma y mezcla conceptos, así como también abriendo el campo intelectual de una inmensa producción local y regional de teoria social, política y estética.

Este ordenamiento material e institucional donde disciplinas y programas se aticulan, genera el espacio para la emergencia de epistemologías y metodologías propias del Sur, no solamente articuladas en torno a las “memorias del subdesarrollo” (por citar el título de un film modernista cubano) es decir, mediatizadas por la falta de recursos financieros e infraestructurales, sino también generadas en respuesta a problemas regionales y locales singulares, diferentes a los hallados en los países “centrales” y que necesariamente requieren de conceptualizaciones y métodos e investigación y pensamiento diferentes. Este paisaje de conceptualizacion epistémica y metodológica innovadora, se contrasta con el resto de producción de conocimiento social en el Sur, de tinte tecnocrático, mayormente determinada por las presiones y demandas de financiamiento y orientación ideológica de las agencias multilarales, de la industria del desarrollo y de la gobernabilidad, así como por el modelo del paper, el informe y la consultoría. Estas estructuras a través de su poderío político-económico intentan condicionar la producción de pensamiento en el Sur, determinando el espacio de lo que es posible pensar, lo cual en general es acotado a la escala la solución de problemas técnicos, reduciendo lo político al cálculo utilitario y a la “buena gobernabilidad”.

La producción innovadora y creativa de teoría, que de modo singular emerge en el sur, abre el espacio para un debate sobre la economía política del conocimiento. Cuál es el valor agregado que provee la teoría producida en el sur a los mercados del capitalism cognitivo contemporáneo y de la actual sociedad de la información en donde el saber es la principal fuerza de producción? Quién teoriza al Sur? Quién tiene acceso a conceptos e informaciones importados del exterior, que luego pueden ser modificadas, o pueden dar lugar a la generación de conceptos propios? Qué élites de conocimiento, sociales y políticas, son las generadoras de pensamiento? Cómo se han generado y consolidado estas élites? Están abiertas a modificaciones y transformaciones, pueden co-existir con el surgimiento de nuevos actores epistémicos que generen teoría? La exploracion de respuestas a estas y otras preguntas similares sobre el significado y condicion del Sur global abriría el campo a una discusión acerca de la colaboración y el intercambio intelectual y politico entre regiones del Sur.

Juan Obarrio teaches at the anthropology department at Johns Hopkins university. His research focuses on Africa, state, indigeneity, law, violence. He is the author of The Spirit of the Laws in Mozambique (Chicago Press, 2014) and is in the Programa de Estudios Sur Global, Universidad de San Martin, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

In the contemporary world of high-speed communication technologies and porous national borders, empire building has shifted from colonizing territories to colonizing knowledge. Hence the question of whose voices, experiences and theories are reflected in discourse is more important now than ever before. Yet the global production of knowledge in the social sciences is, like the distribution of wealth, income and power, structurally skewed towards the global North. This collection seeks to initiate the task of closing that gap by opening discursive spaces that bridge current global divides and inequities in the production of knowledge. This chapter provides an overview of criminologies of the global periphery and introduces readers to the diverse contributions on and from the global South that challenge how we think and do criminology and justice.

In the contemporary world of high-speed communication technologies and porous national borders, empire building has shifted from colonizing territories to colonizing knowledge. Hence the question of whose voices, experiences and theories are reflected in discourse is more important now than ever before. Yet the global production of knowledge in the social sciences is, like the distribution of wealth, income and power, structurally skewed towards the global North. This collection seeks to initiate the task of closing that gap by opening discursive spaces that bridge current global divides and inequities in the production of knowledge. This chapter provides an overview of criminologies of the global periphery and introduces readers to the diverse contributions on and from the global South that challenge how we think and do criminology and justice.