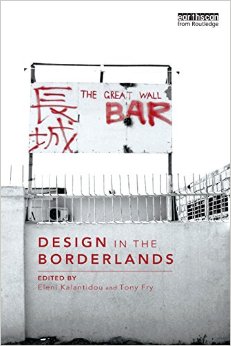

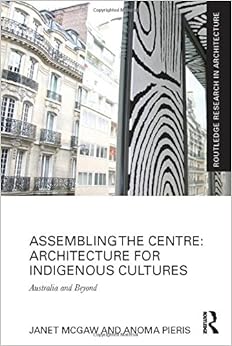

McGaw, Janet, and Anoma Pieris. 2014. Assembling the Centre: Architecture for Indigenous Cultures: Australia and Beyond. 1 edition. New York: Routledge.

McGaw, Janet, and Anoma Pieris. 2014. Assembling the Centre: Architecture for Indigenous Cultures: Australia and Beyond. 1 edition. New York: Routledge.

Series: Routledge Research in Architecture

A new book looks at issues around the architecture of Indigenous cultural centres. It confronts the challenge of de-colonising architecture through a methodology of mutual engagement. This includes discussion of the possum-skin cloak, which has been used by members of the Kulin nation in south-east Australia as a way of representing the gathering of communities. This form of mapping is related to the Deluezian concept of striated representation of space.

Below is the opening of the chapter ‘Skin’ (pp. 152-3) which discusses this form of representation:

Over the past century the expressive potential of the material and tectonic qualities of architecture has in many ways been superseded by the repre – sentational opportunities of the surface (Leatherbarrow and Mostafavi 2002, p. 8). The development of the free façade with the Monadnock Building in Chicago 1891 liberated the surface from its structure, but subsequent structural innovations with tensile fabrics, pre-stressed concrete shells and, more recently, the integration of generative digital software with industrial production, have allowed architects to dispense with orthogonal order as well. The emergence of complexity theories in mathematics and increasingly sophisticated computer intelligence have been critical enablers of this archi – tectural turn since the late the twentieth century. Digital design tools have become generative rather than simply representational, enabling a com – plexity previously associated with craft to be reproduced at a grand scale. Many but not all of these innovations have been aesthetically motivated.

At the same time, a parallel architectural discourse influenced by post – structural literary and feminist theory (by scholars such as Michel Foucault, Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray and Hélène Cixous), has called into question other aspects of the surface. Architectural theorists and philos ophers Elizabeth Diller, Jennifer Bloomer, Elizabeth Grosz and others, have challenged architecture to consider the inscriptive practices perpetuated by a male-dominated profession on the gendered body. Their work drew out similarities between architectural and urban surfaces and bodily skins. The third wave of feminist discourse, through the work of bell hooks, Chandra Talpade Mohanty and Trinh T. Minh-ha has extended the critique to include other ‘minored’ bodies. Relatively few Indigenous cultural centre designs have been informed by these critiques, and yet Indigenous place-making practices have a long-standing relationship with surfaces – both ancient and modern.

We chose the term ‘skin’ – a term commonly substituted with ‘surface’ in architectural discourse – to frame our discussion for its more immediate bodily connotations. Interestingly, skins are at once material and expressive surfaces, a site of inscription and marking. As a vehicle for assembling and

stabilising social identity, the skin has a significant history. In this chapter, we explore the importance of skin as a site of place-making through three historic periods. The connections between inscriptive practices and Storyplaces in pre-colonial Indigenous culture are addressed first. We argue that painting, etching, and other kinds of surface markings in pre-colonial culture were not purely decorative; they had particular symbolic content that some scholars have likened to text. However, we prefer the term ‘(s)crypts’ coined by Jennifer Bloomer, as it alludes to writing (script) that has both spatial (crypt-like) and enigmatic (encrypted) qualities, about Stories that are often sacred (scriptural) (Bloomer 1993).

During the colonial period, new motifs were introduced. The rock art of this period – an early graffiti written over Story-places – reveals the social upheaval that took place as a result of colonisation. The moment of colon – isation signals a process of de-territorialisation enacted through a range of bodily inscriptions by settlers and instituted by the colonial authorities. Thus, the social and physical bodies of Indigenous people were transformed: tradi tional possum skin cloaks were replaced with Western clothes and woollen blankets; initiation ceremonies involving scarification were abruptly ceased; the protective surfaces of ethno-architecture were replaced with institutional buildings. Western garb and architecture became new ‘skins’ that de-territorialised Indigenous social identity. Contemporary Indigenous artists’ responses to these inscriptions include new expressions on the surfaces of the city and the body. They range from the overt, such as stencil, street and body art, to the covert, such as enigmatic inscriptions that retain secret knowledges. Alongside Indigenous voices in this chapter, we include images of surfaces, (sc)rypts and other inscriptions by Indigenous artists. We ask how knowledge of these contemporary practices of re-territorialising Indigenous identity through surface markings might inform a new practice of making Indigenous cultural centres. In particular, we consider how attending to the specificities of Indigenous surface inscriptions might lead Indigenous cultural centre design to eschew aesthetics in favour of politics.

This chapter considers two case studies that do display an overt interest in the surface. The first is international: the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, designed by Jean Nouvel, incorporates a vertical garden on its exterior skin, thus melding living and constructed environments into the fabric of an architecture that explores material innovation in cladding design. However, the Musée du Quai Branly has also been widely critiqued for its application of Indigenous artwork to its interior surfaces as a decorative tool, without reference to the artworks’ cultural contexts or the practices of inscription from which they arise. The second case study is Australian. The National Museum of Australia, Canberra, designed by ARM is a building that engages productively with formal and inscriptive possibilities of the surface to critically challenge political orthodoxies. However, it has also been critiqued as ‘populist’.

McGaw, Janet, and Anoma Pieris. 2014.

McGaw, Janet, and Anoma Pieris. 2014.