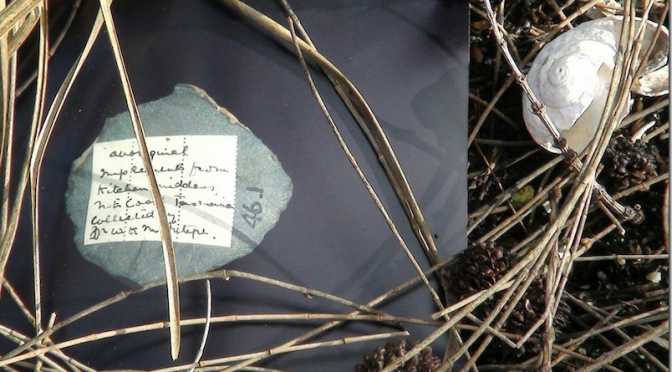

Kay Abude, Piecework, 2014 Steel, MDF, timber, plywood, fluorescent lights, chairs, cardboard, paper, plaster, silicone rubber, paint, brushes, various modeling tools and steel utensils, latex gloves, cotton and nylon rags, cotton velvet, silk, rayon braided cord and workers. Dimensions variable

Piecework, 2014 is an installation and series of durational performances that occur throughout its exhibition in Gallery 2 at Linden Centre for Contemporary Arts. The installation consists of three workstations and three workers dressed in a uniform. The workers engage in an activity of casting plaster objects from moulds in the form of 14.4kg gold bars. These casts are then painted gold. Piecework displays a purposefully futile labour of a repetitive and tireless fashion. It explores a form of work relating directly to performance that is quantifiable, investigating ideas of power and value and asks questions about the role and meaning of labour within artistic practice.

Shift work is characteristic of the manufacturing industry, and the artwork employs performative strategies in a rigorous process and task orientated manner by using Linden as a workplace that is in constant operation over the period of a 24-hour cycle. The ‘three-shift system’ is performed (Shift 1: 06:00-14:00, Shift 2:14:00-22:00 and Shift 3: 22:00-06:00) by the three workers who produce these gold bars throughout the six week exhibition period. The workers are paid a fixed piece rate for each unit produced/each operational step completed per shift. Ideas of the factory are embedded in the vary nature of the work mimicking a manufacturing process carried out by uniformed workers who take up their posts in eight hour shifts.

The catalogue essay by Jessica O’Brien:

The poetry and politics of production

Addressing the intersection between art, life and capitalism, Kay Abude’s Piecework interweaves personal experience, a critique on the distribution of global economic power, and the relationship between producers and consumers.

Piecework unfolds over a six-week period. A durational performance piece highlighting labour and process, the performers undertake manufacturing processes that reference the artist’s personal experience and recent site visits to Chinese factories. The group works through an endless pattern of standardised procedures that result in gold painted serialized plaster ingots. The performances are structured according to a three-shift system, dividing the day into three eight-hour working shifts that mimic a continuous 24-hour production cycle.

By foregrounding the body of the worker, Piecework engages with the pervasive neo-colonial first world practice of exploiting emerging economies and their abundance of cheap, unregulated labour. With most of Australia’s goods produced offshore, the performance addresses the disconnection in the minds of the consumer between the products we buy, and the often dehumanising labour that is required to produce it.

Banal, repetitive, precise and designed for maximum efficiency, Piecework could stand in for the processes behind countless products and could be extrapolated in factories a hundred or a thousand times over. Each action is carefully considered, creating a Haiku-like poetry to the work.

Highlighting the formality existing in standardised production, there is a purposeful ambiguity in the artist’s aestheticised interpretation of reality. Kay writes: “Two different types of labour exist in the two environments of the factory and the studio. The large populations filling the factories are dependent on the market that exploits them. These people labour because they must work for their livelihoods – they work in order to live and survive. The labour present in art practice is one that is voluntary and pleasurable for the artist – the artist lives to work and create.”[1]

Downplaying the desire for a single ‘artist’s hand’ in the work, while expressly displaying the labour that it took to create it, the audience is left to question the value of the objects that are produced, and how it is conferred.

At the crux of these ambiguities is the role of the audience in the artwork. “The fine arts traditionally demand for their appreciation physically passive observers…but active art requires that creation and realization, artwork and appreciator, artwork and life be inseparable.”[2] Utilising the understanding that the relationship between the artist and the audience is at the heart of Performance Art, the seemingly passive and non-participatory viewers of Piecework are in fact directly implicated in the work.

Piecework replicates the role the audience plays as participants of consumer culture, in their role as consumers of the artwork. Abude is the manufacturer and we the consumer. Without a market or an audience, ‘production’, in every sense of the word, would not exist.

By foregrounding the human process by which consumer goods are made through the physical presence of the workers, Piecework addresses the disconnection and compartmentalisation that is characteristic of present day consumption in a capitalistic society. And yet it also replicates those very relationships, distilling and aestheticising disturbing imbalances of power.

As Claire Bishop’s remarks: “The most striking projects… [hold] artistic and social critiques in tension.”[3] Piecework is a considered response to a pervasive social issue, but does not attempt to present a fixed meaning, or take on the herculean responsibility of suggesting a solution to global economic inequality. As unwitting participants of the performance, the significance we chose to ascribe to our role as a consumer of product and artwork is up to us.

Jessica O’Brien

June 2014

Jessica O’Brien is an independent curator and writer based in Melbourne.

[1] Abude, Kay, Put to work, M Fine Art, Faculty of the Victorian College of the Arts and Music, The University of Melbourne: November 2010, p. 28.

[2] Kaprow, Allen, Essays in the Blurring of Art and Life, Berkeley: University of California Press: 2003, p. 64.

[3]Bishop, Claire, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, Verso Books: 2012, p. 277-8.