“Passion for the land where one lives is the foundation of belonging and is an action we must endlessly risk.” Eduoard Glissant

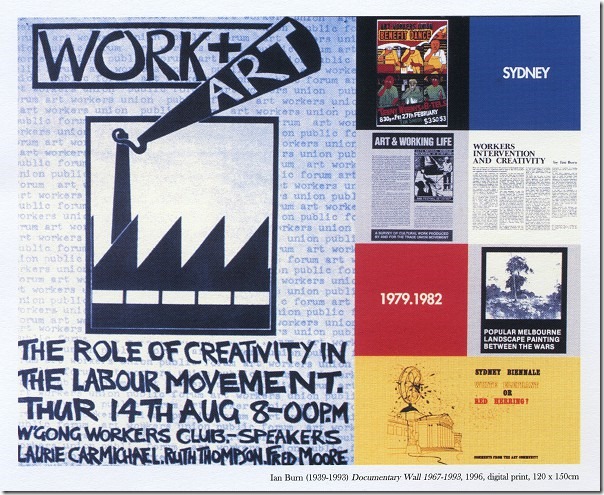

Previous roundtables explored strategies for countering the commodification of art through the practices of the gift and openness. The Sydney roundtable brought together artists and writers who have an interest in local context. In a peripheral country such as Australia, the international stage beckons as a recognition of worthiness. The goal was to propose how the local might be represented without seeming parochial.

It was the evening of Bloomsday, an international celebration of locality in space and time, marking the day’s journey through Dublin. The discussion was located in Addison Road Centre, a long-established precinct for cultural activity in the inner-western suburb of Marrickville. The various tenants there, representing diverse ethnic backgrounds and scavenging economies, reflect an local resilience.

The participants focused particularly on the understanding of place as a key goal. One aspect involves knowledge of local plants, particularly their names and how they might be used in cooking and/or medicine. The process of gathering this knowledge draws on the different cultures that inhabit this place, which have alternative ways of using what can be found. Underpinning this is a belief that paradise is here on earth.

A number of shared opinions underpinned this focus on place.

Post-colonial guilt is no longer useful. It has the effect of alienating us from place. Respectful acknowledgement of traditional ownership should not stop us embracing our responsibility for looking after our part of the world.

An important means of gaining local knowledge is walking. Walking not only helps us discover the local, it connects disparate elements together through experience. Walking need not only be an individual action, it can also include collective actions such as parades and marches.

The challenge emerges of how to locate this local. Within the concentric context of the ‘international’, the local is inferior. The local is less advanced and less informed than the metropolitan centre.

Within the perspective of Southern Theory, the local acknowledges its dependence on context, whereas the metropolitan centre presumes a universalism that denies its own locality.

One proposal to explore this perspective is to find a way of linking localities together that is not hierarchical. Working at the level of council, there is potential to activate connections between suburbs similar to Marrickville in Sydney, such as Brunswick in Melbourne and Tlalpan in Mexico. Similar processes of place-making such as foraging should be undertaken in different geographically distant localities. The results could then be shared. The common experience offers a sense of solidarity to counterbalance the centripetal pull of the metropolis.

There is potential to formalise this into an event like a locally distributed biennale. This would involve identifying a specific time period in which events would occur and be shared between different places. Alternatively, it may be possible to consider connections based on contrast, such as the different political orientations of Sydney’s Marrickville and North Shore.

Questions which arise from this idea include:

- What activities of place-making might be shared between different localities?

- How do you prevent the focus on local becoming insular, consolidating common values while excluding difference?

The idea of a rhizomic biennale is now open for future development.

Participants: