Life, at times, imitates art.

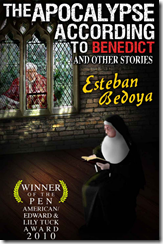

In the novel, “The Apocalypse of Benedict” (El Apocalipsis según Benedicto) published in 2008, prize-winning Paraguayan author, Esteban Bedoya, accurately describes the Pope’s retirement at the age of 85. Incredibly, one paragraph of Bedoya’s novel reappeared 2 years later in 2010, when Benedict XVI, in an interview (which was later published as a book) with a German journalist, expressed a possible condition for his retirement. At the end of Bedoya’s short novel, after his retirement, the ex-Pope was continued to be called “Benedict”.

In the first part, with an admirable writing style that is both precise and surgical, Bedoya tells a story, very similar to reality, of the public life of Benedict XVI, whose full name is Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, who after the death of John Paul II, was elected as the 265th Pope on the 19th May, 2005.

In the second part, Bedoya unleashes his creativity and, amongst other events, Benedict XVI resigns. What follows, is a recommendation for anyone who has yet to read the book: to get themselves a copy and read it.

But it’s not just by coincidence or chance that Bedoya is lead to such an accurate prediction. It is however, the development of the novel that drives and justifies this outcome.

The resignation and retirement of the Pope, detailed in Bedoya’s fiction, is now seen today repeated in reality and has taken many by surprise. Accordingly, use of this fiction should be highlighted as an effective method to interpret and explain what really occurs in the dark, yet elaborate corridors of the Vatican.

One of the extracts from the novel that accurately describes certain sentiments and reasons for retirement which have since been publicly expressed by Benedict XVI himself, years after Bedoya’s novel had been published, includes:

The press speculated and started rumours which spoke of the retirement of the Pope: Benedict himself had announced his intention to resign in the case of being unable to carry out such responsibility (“The Apocalypse of Benedict”, page 21).

Benedict’s sentiment in Bedoya’s 2008 novel, fits perfectly with the paragraph highlighted by the Basque newspaper, GARA, on 12th February 2013 which reads:

The protagonist himself (Joseph Ratzinger), in a book-length interview with German journalist Peter Seewald, confessed in November of 2010 his willingness to “resign due to illness, if physically, psychologically and spiritually (he) were not able to perform (his) job (in: http://preview.tinyurl.com/cy9az8y).

The idea is not to take away potential readers of the novel, so in it, after the resignation, the former Pope was continued to be referred to as Benedict…

In light of this, Cubadebate published the article: “Lombardi: We will continue to call him Benedict XVI” (in: http://tinyurl.com/bu7vd4r).

It’s worth highlighting the film “Habemus Papam”, by Italian film director Nani Moretti, which tells the fictional story of Cardinal Melville, who, when elected Pope, suffers a panic attack that prevents him from taking office. However, in the case of the Bedoya’s novel, both the identity and age of the Pope who decided to retire is actually depicted: the same Joseph Ratzinger – Benedict XVI, at age 85.

To think that a Pope can retire is not something extraordinary, even though the last time it happened was 598 years ago, but to actually predict the name and age of the Pope who has now, in real life, resigned and retired…. well that’s a different story.

In turn, author Frei Betto has so far written about five resignations, including that of Benedict XVI:

In the history of the Church there are four popes who resigned …: Benedict IX (01/05/1045), Gregory VI (20/12/1046), Celestine V (13/12/1294) and Gregory XII (04/07/1415). Benedict XVI will be the fifth, as of 28 February 2013 (in: http://tinyurl.com/bfdyls2).

Literature is also capable of writing the history of the future

In delving into universal literature and cases of authors who produced works considered clairvoyant, emerge the names of Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, George Orwell, Ray Bradbury and Manuel Scorza.

Julio Venre was a successful French writer thanks to his ability to attract a very diverse readership. He captivated audiences by pioneering the science fiction genre and his works were not only popular in his time, but even still today.

He predicted with great accuracy in his fantastic tales the appearance of some of the products generated by the technological advances of the twentieth century; TV, helicopters, submarines and spaceships (in: http://tinyurl.com/ylmn3om).

Herbert George Wells was a writer, novelist, historian and British philosopher. Wells wrote science fiction novels such as “The Time Machine” (1895), whose original title was “The Chronic Argonauts”, “The Invisible Man” (1897), “The War of the Worlds” (1898) and “The First Men in the Moon “(1901).

George Orwell, under the pseudonym of Eric Blair, was a British writer, and wrote the novel “1984” in 1948. Perhaps this title arose as a rearrangement of the last digits of the year to place the work in the future. It is often cited as a counterexample to a utopia (an imagined place in which everything is perfect), with “dystopian fiction” (an imagined place in which everything is undesirable). In this book the concept of “Big Brother” emerges; a police state which is totalitarian, vigilant and repressive, as it used to be three decades ago, due to results of projects like “ECHELON” (UKUSA Security Agreement: United States, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand).

Ray Douglas Bradbury, American science fiction writer, wrote fantasy stories with a poetic prose such as; “The Martian Chronicles” (1950), “The Golden Apples of the Sun” (1953), “A Medicine for Melancholy” (1960), “The Machineries of Joy” (1964) “Ghosts of the New” (1969), and among his novels, the unforgettable “Fahrenheit 451” (1953), is also highlighted as part of his dystopian fiction.

Manuel Scorza, excellent writer, poet and social activist from Peru, wrote the monumental epic series “The Silent War”, composed of five novels: “Drums for Rancas” (1970); “Garabombo, the Invisible” (1972), “The Sleepless Rider “(1976), “The Ballard of Agapito Robles”(1976) and “Requiem for a Lightning Bolt” (1978). In the latest of the series, Scorza wrote about certain characters and their actions which, two years later, came true in a few sociopolitical cases in Peru.

However, in the case of “The Apocalypse of Benedict” Esteban Bedoya went a step further, venturing into unchartered territory and creating a piece of literature which, five years ago, described with amazing accuracy something that then was the future and today is now the present.

International recognition of Bedoya’s nouvelle format

In some proposals for the classification of novel literary works nouvelle or novella is a story of a lesser extent than a novel and is defined by Julio Cortázar as a “genre somewhere between a story and a novel.”

With respect to the number of words in a nouvelle, some authors set their limits between 30,000 and 50,000 words, but it is not an inflexible rule. Two nouvelle works are: “The Tracker” by Julio Cortázar and “Perjury in Snow” by Adolfo Bioy Casares.

This extension which responds to the nouvelle format is apparently where Esteban Bedoya is most comfortable. “The Apocalypse of Benedict” in its Spanish version has 13,389 words and in English, 14,756. His excellent nouvelle will be republished under the title of “The Ear Collector” and in its Spanish version will be 35,914 words.

The novel “The Apocalypse of Benedict” is not limited to the accuracy of the story and guessing what happens now in 2013, it has outstanding literary merit pertaining to both the structure and the level of creativity. In fact, for this work Bedoya received the 2010 PEN America/Edward and Lily Tuck Prize for Paraguayan Literature.

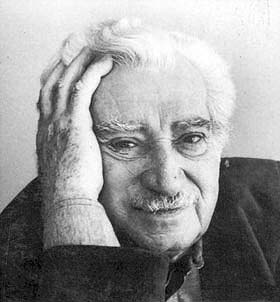

As a writer, Bedoya has also received awards from the Academy of American Poets (1982) and publisher, Helguero (1983).

His much publicized novel “The Bear Pit” (2003), was translated into French under the title “La fosse aux Ours” (2005), the German title “Der Bärengraben” (2009) and published in France by La dernière Goutte.

His novel “The Evil Ones” (“Les Mal-aimés”) (2006) was translated and published in France as by L’Haremattan and the novel, now titled “The Ear Collector” will be translated into French and published in France by La dernière Goutte.

“The Apocalypse of Benedict” is being translated into English for publication in the United States.

After ten years of his creative work being published, Esteban Bedoya’s writing continues to increase in creativity, with genuine stories that are not only worthwhile reads, but are enjoyed with the same pleasure as that of the best of Augusto Roa Bastos.

Article by Vicente Brunetti from Kaos en la Red (translated by Gabrielle Hall).

.jpg)