This paper by María Helena Lucero was delivered at the Southern Perspectives series at the Institute of Postcolonial Studies on August 11 2011. It introduces recent Latin American thinking about modernity, particularly in the concept of the ‘decolonial’.

Beyond the Favela, the Rua and the Museum: Reading Hélio Oiticica and Artur Barrio from Decoloniality.

Fluctuations and Paradoxes of a Latin-American Modernity[1]

I

Thinking about modernity in Latin America implies revising the works of certain artists who have been protagonists of episodes of rupture in the local as well as in the international cultural arena, including the decades of the 1960s and 1970s. As we move in this direction, it is possible to recognize visible signs of a decolonial position in two emblematic artists of Brazilian, and thus Latin American art: Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980)[2] and Artur Barrio (1945). The aim of this paper is to focus on a reading of these two visual trajectories, from a critical perspective that is rooted in what Ramón Grosfoguel and Santiago Castro-Gómez (2007) have called the “decolonial turn,” given that it is necessary to re-evaluate certain cultural itineraries from an adequate epistemic framework if we are to concern ourselves with a Latin American specificity. Decoloniality formulates a vision of knowledge that is compatible with that of postcolonial studies, an aspect that will also be taken under consideration. In this way, the development of theoretical perspectives that aim for the expansion of discussions around the global-south implies pluralistic modes of perception and interpretation of the cultural productions that emerge there.

Thinking about modernity in Latin America implies revising the works of certain artists who have been protagonists of episodes of rupture in the local as well as in the international cultural arena, including the decades of the 1960s and 1970s. As we move in this direction, it is possible to recognize visible signs of a decolonial position in two emblematic artists of Brazilian, and thus Latin American art: Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980)[2] and Artur Barrio (1945). The aim of this paper is to focus on a reading of these two visual trajectories, from a critical perspective that is rooted in what Ramón Grosfoguel and Santiago Castro-Gómez (2007) have called the “decolonial turn,” given that it is necessary to re-evaluate certain cultural itineraries from an adequate epistemic framework if we are to concern ourselves with a Latin American specificity. Decoloniality formulates a vision of knowledge that is compatible with that of postcolonial studies, an aspect that will also be taken under consideration. In this way, the development of theoretical perspectives that aim for the expansion of discussions around the global-south implies pluralistic modes of perception and interpretation of the cultural productions that emerge there.

Hélio Oiticia

|

Artur Barrio

|

Hélio Oiticica has gone through different artistic stages, from the two-dimensional paintings we associate with the Frente group in the 1950s to his Cosmococas in 1973, or actions born out of “contra-bólido”’ toward the end of the 1970s. His explorations resulted in theoretically complex, vigorous, and coherent constructions, that drew a personal itinerary that stimulated a “permeable corporeity”: he would activate not just a connection with certain surroundings, but also perceptual channels that, at times of oppression, would work as zones of self-conscious liberation and as decolonial signs. Artur Barrio initiated, toward the end of the 1960s, a series of interventions in urban and peripheral zones in Rio de Janeiro and Belo Horizonte. His well-known trouxas ensanguentadas, pieces that alluded to physical remains that were wounded or devastated, operated as provocation devices that altered the perception of the unaware walker-by, who would come across these disturbing packages that were squirted and stained with a violent red as he stepped along the city sidewalk.

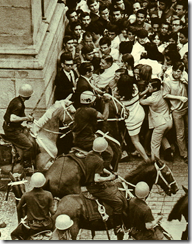

Both trajectories have shown us visual propositions that, on one hand, instituted regional expressions within an international artistic arena, expressions that are tied to the subversive character of Latin American conceptualism –a counter-discourse strategy that questioned the political hegemony of the State and the fetishist condition of legitimated art. On the other hand, they openly rejected the military dictatorship that took place in Brazil (1964-1985), which reached its crudest and most violent moment in 1968, when the law AI 5 was passed to suppress the civil and political liberties of Brazilian citizens.

II

Before developing the concept of decoloniality, let´s consider the academic backgrounds of the members of the modernity-coloniality network, the nucleus from which the concept arises. Certain Latin American intellectuals, among them Aníbal Quijano in 1996 and Ramón Grosfoguel in 1998, while working in U.S. universities, began to debate colonial legacies, the geopolitics of knowledge, and the coloniality of knowledge in Latin America. Up to par with researchers like Santiago Castro-Gómez, Walter D. Mignolo, Edgardo Lander, Fernando Coronil or Enrique Dussel, these intellectuals participated in the activities of the modernity-coloniality network. As do Cultural and Postcolonial Studies, “…el grupo modernidad/colonialidad reconoce el papel esencial de las epistemes, pero les otorga un estatuto económico, tal como el análisis del sistema mundo” [… the Modernity/Coloniality Group recognizes the essential role of epistemes, but it assigns them an economic status, like world-system analysis] (Castro-Gómez, Grosfoguel, 2007: 16-17). This epistemic frame is in some ways linked with the theories of Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Spivak, but it has also avoided automatically introducing postcolonial reflections on the Latin American stage, in order to examine regional singularities and to consolidate a discussion on Occidentalism “by and from” Latin America. It is in this context that the term “post-occidentalism” has gained currency, as a reformulation that conjugates decolonization and postcolonialism, where knowledge is forged in interstitial or hybrid ways, “…pero no en el sentido tradicional de sincretismo o ‘mestizaje’, y tampoco en el sentido dado por Néstor García Canclini a esta categoría, sino en el sentido de ‘complicidad subversiva’” [… but not in the traditional sense of syncretism or ‘mestizaje’, and also not in the sense given by Néstor García Canclini to this category, but in the sense of ‘subversive complicity’] (2007: 20).

Strictly speaking, decoloniality, as it has been mapped out by Castro Gómez and Grosfoguel, insists on the liberating nature of the term and encourages a second decolonization—of an intellectual and cultural nature, in comparison with a first decolonization that is restricted to the legal-political level, achieved by the Spanish colonies in the nineteenth century and the British and French colonies in the twentieth century. The transition from modern to global colonialism took place without a substantial transformation of binary organizations, such as the economic poles of centre-periphery, thus reproducing political and economic submission. The crisis of the modern condition produced cracks and variables in the historical canon of power that denied multiplicity, superposition or hybridity, making a turn toward increasingly plural global presences. In spite of these changes, the colonial traces of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries have endured. Thus, it follows that the decolonial perspective pushes for a culture that is intertwined with decisive effects on ethnic, racial, sexual, epistemic, and gender dimensions. In and of themselves, racial discourses provoke negative consequences in the international labour system, a worrisome aspect for decoloniality.

Racial premises would justify the access of supposedly “superior races”[3] to better offers in the labour market, as opposed to the “inferior races” that would be relegated to badly-remunerated tasks, thus tracing a way of thinking that inherited notions of the nineteenth century. This condition should be examined from a heterarchical perspective, where no level exists that dominates or subjugates others but, instead, there is a multiple and shared influence that works for a new and better paradigm. Let us remember that the idea of heterarchy, developed by sociologist Kyriakis Kontopolous, is antithetical to hierarchy and undertakes the analysis of social structures by including dysfunctional aspects in a partial, discontinuous, and non-homogenous way. Likewise, decoloniality confronts coloniality of knowledge, which is grounded on an economic dimension as well as on mechanisms of social control. As Mignolo (2007) has noted, decolonial thought has been configured as a resistant and different zone from modernity/coloniality itself. In this manner, coloniality exteriorizes the situation of domination of those who have been forcibly submerged in modernity.

Even though the theoretical alignment of the modernity/coloniality group traces differences and relocations with respect to postcolonial studies, they do share its interdisciplinary and deconstructive character with respect to the Eurocentric, colonial paradigm. Mellino (2008) has presented a revision of the term “postcolonial” in order to delineate a genealogy of its repercussions and incidences in the international academic world. He makes a distinction between a literal and a metaphorical interpretation of the concept of postcolonialism. In the first case, it would refer to a “post” moment of decolonization in the political arena, or forms of emancipation from territorial colonization at a given time period; in the second case, there appear far-reaching implications that are not contained within a segment of time. The crucial precedents for this way of thinking are to be found in Edward Said, an intellectual associated with anti-imperialist criticism; in Gayatri Spivak, who detects, in British literature, the echoes of colonialism and imperialism that subsist beyond the multiple cultural meetings, contacts, and shocks between Orient and the West; and in Homi Bhabha, whose expressions of “hybridity” or “the in-between” have endowed us with the capacity to give a name not just to the cultural interstices forged on fluctuating borders, but to new social actors who do not have a fixed locus. Here, postcolonial criticism works through the deconstruction of the Western imperialist subject, exploring the degree of epistemic violence in the narratives that are cast upon cultural alterities.

From Said´s, Spivak´s, and Bhabha´s contributions, the postcolonial paradigm came to be formed as a “desarrollo del pensamiento posmoderno orientado a la crítica cultural y a la deconstrucción de las nociones, de las categorías y de los presupuestos de la identidad moderna occidental en sus más variadas manifestaciones” [development of postmodern thought aimed at cultural criticism and the deconstruction of the notions, categories, and presuppositions of modern Western identity in its most varied manifestations] (Mellino, 2008: 51). For Homi Bhabha, colonial discourse attends to a system of symbols and practices that organize social reproduction in colonial space. According to him, the sense of “post” that is implicit in the term “postcolonialism” refers to a “beyond” and embodies a certain “inquietante energía revisionista” [unsettling revisionist energy] (Bhabha, 2007: 21) that has the ability of transforming the present into a locus of experience and plurality. In this operation (which, in the end, assumes a political stance), culture makes up a seminal dimension, founding a “estrategia de supervivencia es a la vez transnacional y traduccional…” [strategy of survival that is at once transnational and translational…] (2007: 212) and that establishes a space “in-between” that allows for the emergence of hybrid and interstitial cultural signs.

III

In order to circumscribe the critical tone of the productions generated by the aforementioned artists, let us remember that the tone that preceded conceptualism in Latin America stimulated reflections on the idea of dematerialization. Mari Carmen Ramírez (2004) has pointed out that this cultural project did not depend on centre or metropolitan phenomena, but transcended the opposition “centre-periphery” and accentuated structural and ideological factors over perceptual conditions. A systematic “inversion” occurred through Latin American conceptual experiences with relation to the North American model, given the conditions of marginalization and repression that Latin America experienced in the 1960s and 1970s. The revision of conceptualism in these latitudes obliges us to approach it as “the recovery of an emancipatory project” (Ramírez, 1999: 557). These incipient enunciations predict developments in global conceptual art from an eccentric position, outside or displaced from the centre. Luis Camnitzer underlined certain mechanisms that marked Latin America as a “cultura de resistencia en contra de culturas invasoras” [culture of resistance against invading cultures] (Camnitzer, 2008: 31), whose visual and formal productions pollinated dimensions of the political along with poetry and pedagogy. These sides merged, and the result was a globality that transcended the dichotomy “agitation/construction”: the artist didn’t propose himself as an activist but as a builder of forms, objects, ideas that become embodied in the artwork. There would be a Latin American specificity in contrast with the U.S. conceptual process, observable when taking in account areas such as: the role of dematerialization, pedagogical incidence, the application of the text or literature. For the Latin American case, the process of dematerialization followed a politicized and politicizing condition, more than an aesthetic choice.

Oiticica developed part of his work in the period that immediately preceded as well as during the Brazilian dictatorship. The 1964 Parangolés were capes that were made of ephemeral materials, outside the art circuit. The spectators, besides integrating the work, would make movements in space to the rhythm of Rio de Janeiro samba, thus establishing a dialogue with the surrounding context. In this way, there appeared a new “una experiencia integradora donde la Percepción cumple el doble rol de estructurar y transformar el mundo de lo cotidiano (…)” [integrative experience where Perception has the double role to restructure and transform the quotidian world (…)] (Lucero: 2009a: 2). In 1965, the common denominator among artists and critics was their opposition to the system through protests of a cultural nature, that took place in events such as Propuestas 65 in São Paulo, an event that was similar to Opinião 65 in Rio de Janeiro. These were interdisciplinary exhibits that discussed the fate of the arts after the military coup. Hélio, in Propuestas 66, called this new trend “our objectivity”, thus underlining the avant-garde characteristics of these encounters, as well as promoting a space of experimentalism where subjects could free their imagination and, besides being part of that world, they could also be its creators.

Hélio Oiticica Parangolé P 08 Capa 05 – Mangueira, 1965; P 05 Capa 02, 1965; P 25 Capa 21- Nininha Xoxoba, 1968; P 04 Capa 01, 1964. Image from Ivan Cardoso’s film H.O, 1979. Credits: Catalogue Hélio Oiticica. The Body of Color, 2007, p. 317

Tropicália from 1967 was the product of diverse appropriations, which allowed him to advance his environmental agenda, and can be understood as “an idea of a garden for sensory and graphic experiences” (Figuereido, 2007: 118). The notion of anti-art coined by Helio emphasized the artist´s condition as an instigator of creation and that of the spectator as an active participant of the artwork. Anti-art was the response to a collective need in relation to the creative action, that was exempt from intellectual or moral premises: it was man´s simple position within himself, “in his vital creative possibilities” (Oiticica, 1999: 8). Dance was a direct search for the act of expression, and in contrast with ballet´s mechanical choreography, the movement suggested by the dances of carnaval was the equivalent to the exteriorization of the popular element in these communities. The collision with preconceptions related to artistic practices formulated “the connection between the collective and individual expression – the most important step towards this -” (Oiticica, 2006: 106).

Artur Barrio has been a reader of Frantz Fanon (also Oiticica had a translated copy of The Wretched of the Earth). This is an important detail that helps us understand his plastic choices as well as what it means to produce art in the periphery of capitalism. The reference to residues of cheap materials targeted hierarchies and reflected the idea of “economic leftovers”, or edge of the margin. In this sense, “la obra de Barrio incluye estrategias del Conceptualismo apelando al uso de elementos precarios, banales y frágiles, trazando una opción disidente respecto a los materiales industriales de alto costo económico” [Barrio´s ouvre includes conceptualist strategies, that make use of precarious, banal, and fragile elements that delineate a dissident alternative with respect to industrial, high-cost materials] (Lucero, 2009b: 6). The sum of his aesthetic choices constituted the equivalent of an attitude of resistance against others´ control over his own matter. “La postura estético-política de Barrio es una toma de conciencia en relación a la producción del arte en el Tercer mundo como resistencia a la contramodernidad” [Barrio´s aesthetic-political position is an act of conscience with relation to the production of art in the Third World as resistance to countermodernity] (Herkenhoff, 2008: 15), if we understand “countermodern” in Homi Bhabha´s terms, that is, as related to neocolonialism. In this way, Barrio took a clear position before an instance of oppression, that colonized liberty and the senses. In 1969, the artist piled up packages that were toned with blood in one of the rooms of the Modern Art Museum in Rio, that were presented under the title Situação..ORHHH.OU..5.000.T.E..EM.N.Y…CITY: the word “situation” set a deviation from traditional notions of art, while emphasizing an attitude of spatial intervention. One month later, those packages would be taken to the steps of the garden or to the street. The project became more and more extended and in 1970 Barrio deposited the trouxas ensaguentadas on the banks of the river that runs across the City Park (Parque Municipal).

Artur Barrio Trouxas ensanguentadas, in Situação…T/T1; Belo Horizonte, April, 1970; Credits: Inverted Utopias. Avant-Garde Art in Latin America, p. 370

He then packed five-hundred plastic bags with human remains, such as nails or bones that were splattered with bodily fluids, and he placed them in different sites in Rio and Belo Horizonte. The trouxas were, according to Herkenhoff, evidenciadores or “witnesses” that altered or brought a different dynamic to a particular state of affairs. These evidences or demonstrations translated into: operations of repulsion against countermodernity; distributive circuits in the urban and marginal fabric; objects that were “anxious” to force a confrontation with the visceral fear that emanated from the dismembered or gashed organism; visual contaminations, fragmented bodies, paintings, flesh, and finally, living mud. Also in 1970, he did an ambulatory experience that consisted in spending four days and four nights without food or sleep, and just smoking manga rosa, a seed that is grown (sativa) in Brazil that became popular during those years. His body was the physical support for an action that became effective at every moment, in a way that was erratic and to-the-limit. The artist recorded these explorations in perception in a notebook and eight years later he wrote a text defining the term “deambulário” as a one that was written and inscribed on the body (Klinger, 2007).

In Oiticica, the Parangolés provoked an attitude of emancipation in all of the participant´s perceptive dimensions. Each cape provided a different tactile arsenal, with different textures, and colours, promoting a decolonial sense in two ways: the independence involved in dancing with the piece of clothing, and the liberation of showing revolutionary and rebellious phrases: “be marginal, be a hero.” The Tropicália installation generated feelings of provocation and dislocation because it subverted the order of conventional visuality. There, a cultural need irrupted that made it possible for the subaltern to empower and renew himself, while rescuing the symbolic remains that accumulated in the margins and infiltrated the artistic production, an enunciation that was also political and that grew out of a bastard, emergent territory that induced new, contextualized ways of seeing.

Barrio, on the other hand, swept away with the high cost industrial façade while augmenting the symbolic value of throw-aways from the technological circuit. The trouxas ensanguentadas were furtive cargo that reinforced a decolonial strategy, not just because of the precarious and ephemeral materials from which they were made, but because of their subversive wink against despotism and nationalized torture. He reconstructed private cartographies (the location of the packages) as well as public ones, transforming the urban theatre through minimal interventions that were reiterations but also effective. The wandering that went on for days, that put in risk his physical and mental health, opened an erratic channel that, among other things, allowed him to explore his own bodily limits and his autonomy of action – a personal choice that is articulated within the mode of decoloniality.

IV

Why speak of a Latin American modernity that is vexed by fluctuations and paradoxes? From the field of sociology of communication, Roncagliolo (2003) defines the broad concept of modernity through its chronological and cultural aspects. When we think of the beginning of modernity since the end of the fifteenth century (and through the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries), this temporal category designates, in Berman’s words, a whirl of interacting, parallel phenomena. But this series of vertiginous events were directed toward three potential zones: a nucleus of cultural, scientific, and ethical signification; another of a financial and industrial nature; and another with political roots. The voracious development of economic modernization drove forward the accumulation of capital, an action that was stimulated by the colonization that has expanded toward non-Western territories since the fifteenth century. The projection of these modernising trends in Latin America was attempted with great difficulty, The geo-social reality here differed so profoundly from that of Europe: “América Latina fue una región necesaria para la modernización del mundo capitalista, pero ella misma no se modernizó cabalmente” [The Latin American region was necessary for the modernization of the capitalist world, but Latin America itself wasn’t completely modernized] (Roncagliolo, 2003: 114).

Some of these frictions stem from the persistence of unequal degrees of modernization and, as Achúgar (1993) notes—quoting the Mexican writer Fernando Calderón—, Latin America accepted the cohabitation of the premodern, the modern, and the postmodern. Mixed temporalities exposed paradoxes in our modernity, which provides the conditions of decoloniality.

I have noted here that decoloniality calls for a cultural, artistic, and intellectual decolonization. As a critical category, it refutes Eurocentric views within the field of culture and confronts the heavy weight of coloniality in the realm of knowledge. It opens other senses which, in confrontation with the cultural mainstream, strengthen contortions that betray, perturb, and invert that mainstream. The chain of signifiers is exposed in the objects themselves: the significances disperse, disseminating in the multiple gazes of the spectators. The cultural movements that began in the 1920s and continued in Latin America, and which became belligerently propelled in the 1960s, fought against this condition of coloniality that was rooted for centuries, allowing for the emergence of a “búsqueda de conformación de plataformas de pensamiento propias” [search in the formation of self-made platforms of thought] (Palermo, 2009: 16).

The restitution of local and regional materials, challenging the official status quo of art, and a deeply politicized visual production, are pivotal characteristics of Oiticica’s and Barrio’s installations. Moving their actions to public or socially neglected areas places these aesthetic versions on an institutional edge. At the same time, these artists proclaim, with a most fervent individual freedom, a cultural act that is fuelled by decoloniality. Both Oiticica and Barrio revealed a nucleus of signification that refers to disruptive gestures that, in turn, transcended legitimated art media channels, slipping beyond the favela, the rua, and the museum. They bore witness to a state of crisis not just in their own social and political context, but also in the notion of modernity itself that, as a local phenomenon, was marked by fluctuations and paradoxes, thus producing a cultural convulsion on the Latin American stage.

Bibliography:

ACHUGAR, Hugo. 1993. “Fin de siglo, reflexiones desde la periferia”. In AAVV. Arte Latinoamericano Actual. Exposición, Coloquio. Noviembre de 1993, Museo Juan Manuel Blanes, Montevideo, Uruguay, pp. 85-90.

BHABHA, Homi. 2007. El lugar de la cultura. Ediciones Manantial, Buenos Aires.

CAMNITZER, Luis. 2008. Didáctica de la Liberación. Arte Conceptualista Latinoamericano. HUM, CCE Montevideo, CCE Buenos Aires, Uruguay.

CASTRO-GÓMEZ, Santiago y GROSFOGUEL, Ramón. 2007. El giro decolonial. Reflexiones para una diversidad epistémica más allá del capitalismo global. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Siglo del Hombre Editores, Colombia.

FIGUEIREDO, Luciano. 2007. “’the world is the museum’: Appropriation and Transformation in the work of Hélio Oiticica”. In Ramírez, Mari Carmen. Hélio Oiticica. The Body of Color. Tate Publishing in Association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, pp. 105-125.

HERKENHOFF, Paulo. 2008. “De un Glosario sobre Barrio (dos apuntes: Tercer mundo y Trouxas)”. In AAVV. Artur Barrio. Catálogo de Exposición. Museo Rufino Tamayo, Colección Jumex, México DF, pp. 15-20.

KLINGER, Diana. 2007. “Artur Barrio y Hélio Oiticica: políticas del cuerpo”. In Garramuño, Florencia, et al. Experiencia, cuerpo y subjetividades. Literatura brasileña contemporánea. Beatriz Viterbo Editora, Rosario, pp. 197-205.

LUCERO, María Elena. 2009a. “Diluyendo los límites. Deslizamientos en la práctica artística de Hélio Oiticica (Brasil)”. In AAVV. I Jornadas Internacionales de Arte. Educación en la Universidad. PICEF. Universidad Nacional de Misiones (UNAM), Oberá. CD-Rom, pp. 1-4.

LUCERO, María Elena. 2009b. “Interpelar la opresión: los disturbios de Artur Barrio y Adriana Varejão”. II Congreso Argentino-Latinoamericano de Derechos Humanos: un Compromiso de la Universidad. Facultad de Humanidades y Artes, Universidad Nacional de Rosario (en prensa).

MELLINO, Miguel. 2008. La Crítica poscolonial. Descolonización, capitalismo y cosmopolitismo en los estudios poscoloniales. Paidós, Buenos Aires.

MIGNOLO, Walter D. 2007. La idea de América Latina. La herida colonial y la opción decolonial. Editorial Gedisa S.A., Barcelona.

OITICICA, Hélio. 1999. “Position and Program”. In Alberro, Alexander; Stimson, Blake (editors). Conceptual Art: a critical anthology. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. London, England, pp. 8-10

OITICICA, Hélio. 2006. “Dance in my Experience (Diary Entries)//1965-66”. In Bishop, Claire (edited by). Participation. Documents of Contemporary Art. Whitechapel London, The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp. 105-109.

PALERMO, Zulma. 2009. Arte y estética en la encrucijada descolonial. Cuaderno Nº 6, Ediciones del Signo, Buenos Aires.

RAMÍREZ, Mari Carmen. 1999. “Blueprint circuits: Conceptual art and politics in Latin American”. In Alberro, Alexander; Stimson, Blake (editors). Conceptual Art: a critical anthology. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. London, England, pp. 550-562.

RAMIREZ, Mari Carmen. 2004. “Tactics for Thriving on Adversity. Conceptualism in Latin America, 1960-1980”. In Ramírez, Mari Carmen y Olea, Héctor. Inverted Utopias. Avant-Garde Art in Latin America. Yale University Press, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, pp. 425-439.

RONCAGLIOLO, Rafael. 2003. Problemas de la integración cultural: América Latina. Enciclopedia Latinoamericana de Sociocultura y Comunicación, Grupo Editorial Norma, Buenos Aires.

[1] Translated from the original text in Spanish by Laura Catelli. The citations that appeared in Spanish in the original have been kept in the original language of publication and translated in parentheses.

[2] This presentation has been extracted from my Doctoral Dissertation, Approximations to the Construction of a Methodological Device from the Crossing of Disciplines: Analyzing Productions by Tarsila de Amaral and Helio Oiticica from an Anthropological Perspective. Here, decoloniality is formulated as one of the key concepts for the examination of the artworks.

[3] The term “race” is used here in quotation marks in order to highlight its biologicist and determinist sense. Let us take in consideration that the concept will be debated afterwards, given that it connotes a strong colonialist view that stems from the reflections of authors such as Bernier, Gobineau, Buffon, Renan or Le Bon. For more details, see Tzvetan Todorov’s “Race and Racism” in On Human Diversity: Nationalism, Racism, and Exoticism in French Thought (Harvard UP, 1994).

Dr María Elena Lucero teaches at the School of Humanities and Arts, Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Argentina. She is Director of CETCACL (Centre of Critical Theoretical Studies of Art and Culture in Latin America), Universidad Nacional de Rosario. She is the author of many publications on Latin American art movements and artists, including Eugenio Dittborn, Cildo Meireles and Adriana Varejão. She has also written widely on pre-Columbian cultures.

Please note the upcoming Symposium that SURCLA is organising: Indigenous Knowledges in Latin America and Australia | Locating Epistemologies, Difference and Dissent | December 8-10, 2011.

Please note the upcoming Symposium that SURCLA is organising: Indigenous Knowledges in Latin America and Australia | Locating Epistemologies, Difference and Dissent | December 8-10, 2011.