Southern dialogues are developing strongly at this moment in time, though only to highlight the significant challenges ahead.

Southern dialogues are developing strongly at this moment in time, though only to highlight the significant challenges ahead.

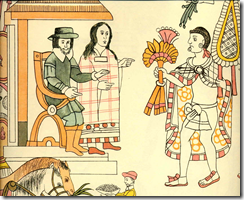

The colloquium Diálogo Trans-Pacífico y Sur-Sur: Perspectivas Alternativas a la Cultura y Pensamiento Eurocéntrico y Noroccidental took place on 8-9 January, as part of the grand scale Congreso Interdisciplinario at University of Santiago, Chile. Latin America has been the home of particularly active southern thinking, inspired often by its indigenous cultures. The ‘south’ as a rallying call has been significant given the tangible counter-influence of the United States, to the immediate north.

The Santiago colloquium witnessed a change away from this previously combative north-south argument. The principal perspectives were from Chile, México and Argentina. Much discussion was given to the emerging relations with Asia, specifically China. Alongside this was the growing influence of Brazil across Latin America, reflected in the large number present for the parent congress. In the past, these south-south relations would have been flavoured by a solidarity against USA as the common hegemon. But now there is increasing recognition of a diversity of interests across the south, and the need to reflect this in a conversation which is not reduced to catching up with the North.

One tangible contribution of the colloquium was the title. The word ‘noroccidental’ literally means ‘north-western’. This refers more generally to Western culture in the North, rather than the top left corner of the globe. Such a term accepts that there is a Western culture in the South as well, particularly in countries like South Africa, Australia and Chile. But it differentiates itself from other northern countries, such as Russia and China.

Other emerging terms are ‘Euro-American’ and ‘trans-Atlantic’. The problem with these is that it uses the generic term to represent only one half—North America. ‘Euro-American’ does not include Latin America, nor does ‘trans-Atlantic’ feature exchanges with Africa. The challenge is to find an English equivalent of ‘noroccidental’. Would ‘north-Occidental’ do?

The plenary concluded with a call for a more global understanding of South, reflecting such developments as population flows through the North and the relational identity of North and South.

The challenge is to extend this dialogue beyond Latin America to engage with forums elsewhere in the South. There is much activity in South Africa at the moment around the book by Jean & John L. Comaroff, Theory from the South: Or, how Euro-America is Evolving Toward Africa, including the recent critical responses in Johannesburg Salon. In Australia, there is continuing reference to Raewyn Connell’s Southern Theory, as well as Indigenous Studies broadly taking on global themes.

The relative lack of connection between these dialogues is, of course, reflective of the condition of the South itself, as a series of spokes connected with each other only via a central hub in the North. Language is an added challenge. The convenor of the Congreso Interdisciplinario Eduardo Devés has developed his own perspective on the Southern condition through ‘periphery theory’, outlined in his publication Pensamiento Periférico, which is freely available in Spanish. The potential reduction of South to the condition of periphery is an important challenge to the broader historical narratives that it carries. To what extent the issues normally identified with South be characterised by the condition of distance from the centre? Such a perspective puts the historical conditions such as settler-colonialism into question.

Though the distances between the southern countries themselves should be identical to those separating northern countries, the ‘hub & spokes’ model works in a very practical way to mitigate against south-south travel. Many academics from outside Chile had to cancel their involvement in the colloquium due to higher than expected air fares. This is obviously compounded by smaller travel budgets for academic staff in southern universities.

Nevertheless, the University of Santiago is taking a lead in fostering south-south dialogue. In late October 2013, they will initiate an annual forum/workshop to ‘go full circle’ on the Pacific, looking at how a trans-Pacific exchange might be configured to include Latin America. The Asia Pacific is usually conceived as a domain exclusive to Australasia, East Asia and North America. But as with the APEC forum, the south-east arc of Latin America should be an integral part of that. ‘Full circle’ provides a focus on the Pacific as a space for multilateral relations. What would be the intellectual underpinning of this?

The time seems ripe for a major conference on these various strands of southern thinking. Given its position, hosting an international conference would seem one tangible contribution that Australia could make to this emerging paradigm. Alternatively, if it were to be held in a northern university, this paradox of having to go North to talk about South would provide sufficient material for a conference in itself.

One question that tangibly brings the condition of southern thinking home concerns the north-south asymmetry of the academic world. In particular, if someone had the prospect of an academic position in Europe or North America, would there be any value in remaining in a less well-endowed southern university?

Meanwhile, while waiting for such an event to emerge, four Australian academics have generous offered a summary of their work accompanied by a generative question:

- Christine Black: Who are your moral heroes?

- Raewyn Connell: How to prioritise the intellectual work of the global South?

- Shaun McVeigh: How to move with honour between laws of the South?

- Lorenzo Veracini: What is the role of geography in sociopolitics?

As the Zapatistas would say, inspired by Mayan mythology, ‘walking we ask questions’. Thankfully, the path stretches out ahead.