Paper for South-South Axes of Global Art (Paris, 17-19 Jun 15)

Context

I present this paper as a curator, more concerned with opening up a space for new possibilities than analysing the past. My purpose is to present alternatives to the biennale model that are conducive to horizontal south-south exchange. Presenting these here, in the cultural capital of the North, affords a critical space to consider its limits and potential for further development.

Before I begin, I need to account for my voice as a citizen of Australia. Australia is an extractivist settler nation that has largely ignored its position in the South in favour of models inherited from Europe and North America. Until recently, the colonial imagination was fired by nationalist tropes like ‘Downunder’, the ‘Great Southern Land’ and ‘Southern Cross’, but these are mere clichés in a neoliberal state that is more concerned with the people it can exclude than the shared stories it can generate from within.

Charles de Gaulle was rumoured to have said of Brazil, that ‘it is a country of the future, and always will be’. So in Australia, our place in the world remains, paradoxically, a distant horizon. But as Paulin Hountondji remarked ‘culture is not only a heritage, it is a project’ (Sahlins 2005). The South is our project, to be more than a colonial outpost. Australia’s distance from the centre has potential to open a space for new possibilities.

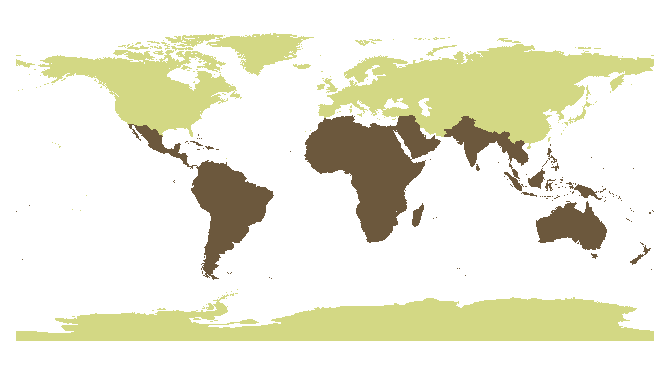

Also before going further I should clarify my use of the term ‘south’. Though it seems uncomfortable in a globalised world to offer spatial limits, I do use ‘south’ as a political reality, more than a convenient trope. Jorge Luis Borges proposed that ‘universal history is the history of various intonations of a few metaphors’ (Borges 1973). Derrida proposed light was one of these key metaphors (Derrida 1978), evident since Plato in the symbol of knowledge as enlightenment. South could be considered among these key metaphors. The meaning of South is predicated on the concept of a vertical hierarchy, where value lies above. It is more than just a trope—an improvement on ‘Third World’, but not as incisive as ‘Majority World’. South cannot be readily transposed. South is a real fixed phenomenon, what Ricoeur calls the vestricktsein, ‘living imbrication’ (Ricoeur 1984, 75). By convention I fly up to Paris, despite that our experience of the world is as in the long run as an even plane. ‘Going south’ has become synonymous with failure. This is a phenomenological function embedded in how we see the world. We live in metaphors, which suits some better than others. Just as blackness is historically tainted with ignorance, so ‘southern’ is by default lowly.

The biennale dream

The story begins with the quest for civic identity. Sydney and Melbourne are Australia’s rival cities. Missing the nature-given attractions of Sydney, Melbourne identifies more with man-made elements, such as its architecture. Through its Major Events strategy, Melbourne also seeks to feature in the international circuit through programs like the Formulae One Grand Prix. But an important piece has been missing. Though originating many of the artistic movements in Australia, Melbourne lacks a place in the international visual arts calendar. Finally, in 1999, it acquired its first, and only, visual arts biennale. Mostly praised by local critics, the event proved a financial disaster. In the end, the Melbourne Biennial didn’t receive the same kind of international funding support that was already directed towards Sydney, one the oldest biennales. At a forum in RMIT Gallery, the godfather of biennales, Rene Block, explained cruelly that there was just ‘no room on the carousel’ for Melbourne. It was too similar to Sydney, which was already established, and did not have the exotic appeal of new members like Istanbul or Gwangju.

This led to many discussions about what it meant to have a biennale in Melbourne. Was there an alternative model? Brisbane had shown how it was possible to consolidate a place in the international calendar outside the carousel, in the Asia Pacific Triennial. Rather try to inveigle oneself into an existing circuit, the Art Gallery of Queensland had created a new set of exchanges framed by an east-west dialogue between Australia and the cultures of its region. At a public discussion at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in 2000, the Brisbane model was explored and the question asked—what new international space could Melbourne help open up?

At that time, the democratic turn in many countries in the South were relatively fresh. Nelson Mandela had just stepped down as President of the new South Africa. In Latin America, countries like Chile, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay had broken with the military dictatorships of the 1970s. The 20th century story of the South as a region of tin-pot dictators and banana republics was no longer relevant. Boycott was no longer the most appropriate ethical engagement with the South. In this context, it seemed that a triennial style event in Melbourne could provide a new space for trying out exchanges with these reformed countries along southern latitudes.

South Project

In 2003, the South Project was initiated and heads of the city’s cultural institutions came together to endorse a future APT style event in Melbourne. In the meantime, however, most of the leading visual arts organisations like the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art reverted back to architecture as a forum of ambition. New buildings like Federation Square testified to Melbourne’s cultural value. It was left to a relatively marginal organisation, Craft Victoria, to carry the South baton. For a craft organisation, the South Project offered not only the potential to forge south-south alliances, it also provided a way to engage with craft practice in an otherwise highly conceptual visual arts scene. The rationale for this came from the relative importance of craft as a means of both livelihood and cultural identity in many countries of the South.[1]

Rather than see this developmentally as evidence of a cultural backwardness, the challenge was to integrate crafts into the platform. This was framed as a democratic issue. Craft helped ensure that this exchange was not simply reproducing the cultural elites that normally ride the carousel, but embraced also those in townships, slums and poblaciones.

The democratic framework was attempted in three ways. The first was to include where possible a local indigenous welcome alongside the inevitable meeting of dignitaries. While now a common feature of public events in Australia, it was still a relatively new component in other countries, particularly South America.

The second was to include practical workshops alongside the standard format of talks and exhibitions. Fibre crafts played a leading role, including Australian Aboriginal techniques in Johannesburg and Māori basket-making in Wellington. This offered craftspersons and artisans with a more direct benefit in attending, as well as opportunity for the university educated participants to engage in a dialogical space was did not privilege their cultural capital.

The third involved exchanges with children. The South Kids program featured the story of an emu that wanted to fly. A kit including the toy emu and camera circulated around schools in the South, enabling children to document their worlds. In Soweto, this was a pretext for praising the capacities of the ostrich, which though unable to fly has unique features such as physical beauty, useful eggs and impressive running speed. The story of the flightless bird was a predicament seen to typify the South, as a region lacking the capacity to share its unique features with each other.

In the end, the South Project did not achieve its grand ambition to establish a triennial in Melbourne. While this was partly the consequence of internal political factors, it was not helped by the relative lack of economic opportunities for Australia across the South compared to the Asia Pacific.

Nonetheless, the South Project left a residual network and a trail of unanswered questions. What does the South share in common, besides a shared opposition to the North? To what extent is the focus on the South reproducing a post-colonial dynamic where indigenous cultures are defined by their oppression, rather than in their own terms? What would be a space such as the South that didn’t need the North to define itself against? A kind of Hegelian dialectic had been initiated to discover an autonomous identity for the South.

Southern Theory

Meanwhile, there emerged a call in the academy to broaden the purview beyond the trans-Atlantic north. In 2007, the book by Australian sociologist Raewyn Connell was published, titled Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science (2007). Connell addressed the degree to which the discipline of sociology was built on a set of interests that were particular to the northern metropolitan centres. She argued that the theories of Marx, Durkheim and Weber did not account for the experiences particular to the periphery, especially that of its subaltern majorities. Rather than the universal systems offered by those theorists, Connell advocated for a ‘dirty theory’ that takes into account the particularities:

The goal of dirty theory is not to subsume, but to clarify; not to classify from outside, but to illuminate a situation in its concreteness. And for that purpose — to change the metaphor — all is grist to the mill. Our interest as researchers is to maximise the wealth of materials that are drawn into the analysis and explanation. It is also our interest to multiply, rather than slim down, the theoretical idea that we have to work with. That includes multiplying the local sources of our thinking, as this book attempts to do. (Connell 2007, 207)

While concerned particularly with the institutional production of knowledge, Connell’s work paralleled others that have recently used the South within a framework of critical social theory. This includes Enrique Dussel’s work constructing a discipline of liberation philosophy (Dussel 1985), which evaluates ideas according to their impact on social justice. Such a philosophy takes geopolitical space seriously. As Dussel writes, ‘To be born at the North Pole or in Chiapas is not the same thing as to be born in New York City.’ (Dussel 1985). This drive has been continued by thinkers and activists such as Boaventura de Sousa Santos, whose epic ‘epistemologies of the South’ (Santos 2013) aims to deconstruct universalising gestures.

There is much diversity among the theorists framing their work in a Southern context (Rosa 2014). But they share the key principle of place as a valid framework for the production of knowledge. This means working in the South can be more than just a second best option, indicative of failure to succeed in the North.

Southern Theory and visual arts

How might Southern Theory apply to the visual arts? Within an ecological framework, ideas are evaluated not only for their internal consistency but also the greater world they make possible. We may thus look at anthropology not as the disinterested study of an exotic tribe for the production of academic knowledge elsewhere, but as an exchange involving solidarity with the aspirations of the community under scrutiny. While Southern Theory is predominantly a matter of reflecting social realities, in the case of creative practices it is more about constructing alternatives to the world as it is.

Walter Mignolo is one theorist who has extended the southern perspective to the practice of visual arts and design (Kalantidou and Fry 2014). From an academic base in Hong Kong, Mignolo has led a group of scholars to develop a ‘decolonial aestheSis’ (Mignolo and Vázquez 2013), which critiques Western aesthetic categories like beauty through practices of juxtaposition or parody. Mignolo highlights the Sharjah Biennial (Mignolo 2013) as an example of radical decentring. According to Mignolo, this event ‘turns its back on the intellectual Euro-American fashions that have dominated, until recently, the “biennial market place”’ (Mignolo 2013). For Mignolo, the value of Sharjah is a matter of its content; the countries and artists that participate represent an alternative ‘cultural cartography’. He notes that of the 100 artists, only 2 were from the USA and 20 from Europe. However, he refrains from mentioning any work in detail. The works are seen to illustrate a particular world view that is independent of the West. An example of one ‘illustrative work’ is:

Nevin Aladag, Turkey, Session (2013). This video triptych shot in Sharjah brings together the topography of the city and percussion music composed with Arabic, African and Indian percussion instruments. The video triptych invokes the spirit of re-emergence in that it works with musical instruments that elude the European renaissance. At the same time, that the instruments are played by and in the environment of Sharjah, cultures once disavowed by western hegemony ‘re-emerge’ with the force and the confidence of pluri-versal futures. (Mignolo 2013)

While its subject may seem non-Western, the format is readily assimilated into the dominant model. It is a ‘white cube’ work, detached from the work, where the visitor is an anonymous viewer. Apart from its geographic location, this work reproduces the biennial model of the world as spectacle.

The current Venice Biennale curated by Okwui Enwezor has brought the concerns of Sharjah to the centre. The majority of works offering a political critique of capitalist hegemony. But as noted (Cumming 2015), there is some irony in an event that is resourced and enjoyed by the very elites it attempts to critique. While some may argue that the carousel is opening up to the South (Gardner and Green 2013), there is no guarantee that it extends beyond the strata of cultural elites found in almost all countries. The challenge is to consider platforms for art making that go beyond reflecting the world as it is, and instead offer alternative pathways for creating a world that might be.

South Ways

It was with the aim to develop alternative platforms that a project was formed last year within the Southern Perspectives, a network of writers and artists that continued after the South Project. The aim of South Ways was to initiate development of platforms for art that act in the world. The process involved roundtables that brought together a variety of voices from those involved in creative practice. Four roundtables were held in different cities of Australia and New Zealand reflecting a diversity of perspectives. To provide a simple pragmatic frame, the seed for each roundtable was provided by a single verb that reflected a distinctive mode of engagement found in the South.[2]

I will provide a brief overview of these verbs and an example of their use.

To bestow

The first roundtable was held in Wellington New Zealand and included a mix of Māori and Pākeha participants. The verb to consider was ‘to bestow’ reflecting the traditional Māori practice of koha or gift giving in art practice and the emergence of Pākeha jewellery forms of engagement involving gift exchange. The main challenge concerned the vulnerability of such practices when exposed to consumer capitalism. Even in biennales, the freebie expectation means that gifts offered as part of the art world are rarely taken in the spirit of exchange. The task was to develop a platform that fostered trust and reciprocity between artists and their audiences.

The project Joyaviva was an exhibition where artists developed prototypes of modern amulets. This drew on the South American tradition of public shrines that receive ex-votive offerings. In the exhibition format, visitors were offered plastic flowers to adorn works and encouraged to reflect on the impact of these amulets on their lives. One of the participants, the Māori artist Areta Wilkinson, integrates koha into both her art work and academic research. For Joyaviva, she featured an initiative to support a Māori community devastated by the Christchurch earthquakes, which included a Matiriki brooch symbolising the Pleiades constellation that signals the New Year.

To open

Melbourne was the site of the second roundtable. Initially, the verb to open related to the work of artists like Nicholas Mangan who chose to expose sites of production in art galleries, such as guerrilla supply lines or factory assembly belts. Present were some of the artists who had chosen to boycott the Sydney Biennale because of its association with Transfield, the company commissioned to manage offshore detention centres. As befits the birthplace of Julian Assange, the Melbourne gathering advocated for a radical transparency, which would highlight the economic value that artists contribute for sponsors to major art events. The proposed WikiLeaks style of platform has yet to emerge.

But one initiative that does aspire to this is the Sangam Project. This platform emerged from the context of the practical workshops in the South Project, where North and South sometimes met in the process of product development, where designers and artisans sought to build creative partnerships. The program attempts to use the new e-commerce platforms as a means to give economic value to the information about the maker, otherwise unacknowledged. This aspires to platform that is alternative to the commodity circuits that occlude the means of production.

To swap

In Sydney, the verb ‘to swap’ was set up to reflect the phenomenon of reverse primitivism in which Southern artists turn the exotic gaze back on the North. In the end, the subject of contention again was the biennale. In this case, the issue was the way the carousel privileged the art of international relations, rather than local practices that draw on urban nature and community histories. The proposal was a distributed biennale which spread its program across local sites in different cities.

An existing example is the project Minga Sistemas de Trabajo Colectivo in Santiago, curated by Angela Cura Mendez and Felipe Cura (Donoso 2015). Minga is a precolombian term for collective labour. In the island of Chiloe, it often takes the form of a Tiradura de casa when the community gather to move someone’s house to a different location. Working with the community of artist-run art spaces in Chile, this exhibition involved gathering more the spaces themselves than work within them. Maria Gabler re-constructed the walls of Galería Tajamar, which exists in a public housing estate, within Galleria Gabriela Mistral in downtown Santiago. This Minga of contemporary art enables a concentration of work that still retains its locatedness within its home community.

To glean

The roundtable in Hobart was concerned the practice of recovering what is left over, ‘to glean‘. This reflected not only the arte Povera practices such as El Anatusi, granted the Golden Lion in Venice for sublime recycling, but also recovery of cultures lost during the process of colonisation, which was particularly dramatic in Tasmania. The discussion eventually led to the revival of the idea of a Museum of Southern Memory, initially proposed in the first South Project, reflecting the common experience of Apartheid, Stolen Generation and the Disappeared. This museum will not be a physical structure, but a network of individuals and groups that sustain a story or cultural practice through use.

This year, the project of a Social Repair Kit involves re-modelling traditional forms of conflict resolution through blood money. The ‘sorry object’ is the subject of workshops in Bogotá, Santiago and Melbourne. The focus is the injury sustained by conflicts such as the Colombian civil war, coup against Allende and last year’s Sydney hostage siege and consequent islamophobia. Rather than reflect on these conflicts, the aim is to draw inspiration from traditional modes of conflict resolution, such as the Palabreros, in order to develop objects that can be introduced into the communities to facilitate apology and pardon.[3]

Conclusion

South Ways is a scattering of seeds, each with a kernel of action. Of course, we need to be realistic about the likelihood that these proposals will flourish, given the kind of soil in which they are planted. Stepping off the carousel means leaving behind the capital which it has proven effective in gathering. The success will depend on the strength of solidarity rather than self-interest of participants. But if South is to be more than a primitivist mirror to the North, it needs to be a space were we can test out other ways of being.

Notes

[1] See (Skinner 2014) for a more developed framework for the importance of craft in a settler colonial art history.

[2] The theoretical framework for this use of verbs is Actor Network Theory, which offers a flat explanatory structure that does refuses the mimesis and instead identifies the effects that accompany representation (Harman 2014). Accordingly, the dominant verb in visual arts is ‘to explore’ or ‘to examine’. This colonial mode entails a distance between the active world of the artist and unknowing object of knowledge. Viewed in this way, the challenge becomes identifying alternate actions in the world.

References

Borges, Jorge Luis. 1973. “Pascal’s Sphere.” In Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952, translated by Ruth L. C. Simms, 1st British ed. London: Souvenir Press.

Connell, Raewyn. 2007. Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science. Cambridge; Malden, MA: Polity.

Cumming, Laura. 2015. “56th Venice Biennale Review – More of a Glum Trudge than an Exhilarating Adventure.” The Guardian. Accessed June 14. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/may/10/venice-biennale-2015-review-56th-sarah-lucas-xu-bing-chiharu-shiota.

Derrida, Jacques. 1978. “Violence and Metaphysics: An Essay on the Thought of Emmanuel Levinas.” In Writing and Difference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Donoso, Diego Parra. 2015. “Cuidado: Zona de Autogestión Apuntes sobre Minga en Galería Gabriela Mistral.” Revista Punto de Fuga. http://www.revistapuntodefuga.com/?p=1774.

Dussel, Enrique. 1985. Philosophy of Liberation. Vol. 1. Maryknoll, N.Y. : Orbis Books, c1985.

Gardner, Anthony, and Charles Green. 2013. “Biennials of the South on the Edges of the Global.” Third Text 27 (4): 442–55. doi:10.1080/09528822.2013.810892.

Harman, Graham. 2014. Bruno Latour: Reassembling the Political. Pluto Press.

Kalantidou, Eleni, and Tony Fry. 2014. Design in the Borderlands. 1 edition. New York, NY: Routledge.

Mignolo, Walter. 2013. “Re:Emerging, Decentring and Delinking.” Ibraaz. August 5. http://www.ibraaz.org/essays/59/.

Mignolo, Walter, and Rolando Vázquez. 2013. “The Decolonial AestheSis Dossier.” Social Text. July 15. http://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/the-decolonial-aesthesis-dossier/.

Ricoeur, Paul. 1984. Time and Narrative Vol.1. University of Chicago Press.

Rosa, Marcelo C. 2014. “Theories of the South: Limits and Perspectives of an Emergent Movement in Social Sciences.” Current Sociology, February, 0011392114522171. doi:10.1177/0011392114522171.

Sahlins, Marshall. 2005. “On the Anthropology of Modernity, Or, Some Triumphs of Culture over Despondency Theory.” In Culture and Sustainable Development in the Pacific, edited by Antony Hooper. Canberra: ANU Press.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. 2013. “Public Sphere and Epistemologies of the South.” Africa Development 37 (1): 43–67.

Skinner, Damian. 2014. “Settler-Colonial Art History: A Proposition in Two Parts.” Journal of Canadian History 35 (1): 131–75.

[3] I should also mention a more dispersed project drawing from the Melanesian language of silence to develop a platform outside of discourse. Vakanomodi project is named after the Fijian practice of deep listening to the land.

Image is from the exhibition Mirador, de María Gabler, en Galería Tajamar, Santiago de Chile, 2015. Foto: Sebastián Mejía

If you’re in Melbourne on 11 April, please come along to this important public event. You don’t have to be an employee of University of Melbourne to have an interest in the impact of neo-liberalism on our public institutions.

If you’re in Melbourne on 11 April, please come along to this important public event. You don’t have to be an employee of University of Melbourne to have an interest in the impact of neo-liberalism on our public institutions. McGaw, Janet, and Anoma Pieris. 2014.

McGaw, Janet, and Anoma Pieris. 2014.