28 years ago, the Australian Supreme Court banned the construction of a hydroelectric dam in the Franklin River, Tasmania, in a case which came to be internationally known as Tasmania v. Commonwealth.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the unemployment rate in Tasmania was 10 per cent (the highest in the country), and the local liberal government together with some big businesses and industries saw the construction of the Franklin dam as the remedy for all evils. This, however, required the flooding of a unique ecosystem, which had been declared as part of the World’s Natural Heritage by UNESCO. Against the plan stood the members of the Wilderness Society and the nascent Green Party who, joined by a number of community associations and independent citizens, proposed a different path to growth: one based on the respect for nature.

Eventually getting the support of the national Labor Party, those opposed to the dam generated the largest environmental campaign in the history of this Southern country. Their main argument was that the dam would not only violate the country laws, but also international agreements to which Australia had subscribed. After five years of protests, lobbying and media work, they triumphed and their story became one of the most quoted in the history of environmental litigation.

I cannot help comparing this case with HidroAysén, a project from the Spanish multinational Endesa (subsidiary of Italian Enel) and Chilean Colbún, which involves the construction of five dams in Chilean Patagonia, to generate 2.750 megawatts –fifteen times more than the aborted Franklin Dam! Whereas the energy that was meant to be produced in Tasmania was at least destined for local consumption, in the Chilean case it is not the Patagonians who are going to get the benefits, but the capital, Santiago, and the big mining industries in the North of the country. After the controversial approval of the Environmental Impact Study of the dams last May, what is now under discussion is the other half of the project: namely, a transmission line of 2.300 kilometers that would cut through six national parks and 11 nature reserves, and would mean chopping over 20 thousand hectares of forests. If approved, this would turn out to be the longest line of direct current in the planet (and probably one of the most inefficient, losing an estimated 10 per cent of the energy on the way).

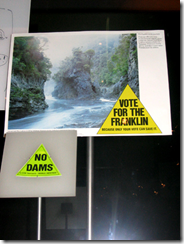

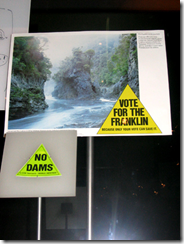

Some people are more prone to be convinced by arguments, while others are more easily persuaded by shocking images, powerful slogans and even musical jingles. The No Dams movement in Tasmania worked on both fronts effectively. On one hand, they won the support of public figures and intellectuals who repeated the message of what would be at stake if the dam were authorized. Together with the organizers, they led the protests, rallies and road blockades, and they even ended up in jail, together with hundred other campaigners. (At the peak of the movement, the Tasmanian prison system simply collapsed, unable to fit them all). Thanks to generous donations, the No Dams campaign could also be heard on the radio –Let the Franklin flow–, but arguably the most effective way to raise the public’s attention were the spectacular photographs taken by Peter Dombrovskis: emerald waters flowing down a rocky patch of the river, surrounded by dense forests and half covered by the early morning mist. “Could you vote for a party that would destroy this?”, was the question posed under the picture by the Labor party, in the federal elections of 1983. Few voters dared to answer in the affirmative, and Labor won with a large swing.

Some people are more prone to be convinced by arguments, while others are more easily persuaded by shocking images, powerful slogans and even musical jingles. The No Dams movement in Tasmania worked on both fronts effectively. On one hand, they won the support of public figures and intellectuals who repeated the message of what would be at stake if the dam were authorized. Together with the organizers, they led the protests, rallies and road blockades, and they even ended up in jail, together with hundred other campaigners. (At the peak of the movement, the Tasmanian prison system simply collapsed, unable to fit them all). Thanks to generous donations, the No Dams campaign could also be heard on the radio –Let the Franklin flow–, but arguably the most effective way to raise the public’s attention were the spectacular photographs taken by Peter Dombrovskis: emerald waters flowing down a rocky patch of the river, surrounded by dense forests and half covered by the early morning mist. “Could you vote for a party that would destroy this?”, was the question posed under the picture by the Labor party, in the federal elections of 1983. Few voters dared to answer in the affirmative, and Labor won with a large swing.

Another important point is that it was understood from the beginning that the decision whether to approve or reject the Franklin dam was not technical, but political. The solution could not come from a mere cost-benefit analysis, because what was at stake was something priceless, namely, what Tasmania wanted to be and to become. The Green Party and its founder, Bob Brown, clearly saw this and, after the battle was won, remained as crucial actors in the Australian political scene: today they are part of the governing coalition, and Brown is one of the most popular senators countrywide.

Finally, the campaign was not so much about opposing, but overall about proposing an alternative path to development. The No to the dam was a Yes to sustainable growth. Three decades later, the decision has proved to be correct. Today, tourism is the second major economic activity in that state, and gives jobs to half a million Tasmanians, it generates a billion dollars annually and it attracts almost a million visitors. Moreover, Tasmania is Australia’s leader when it comes to the production of renewable energy, which amounts to 87 per cent of its total. This comes mainly from wind farms and hydroelectricity (yes, hydroelectricity, but not from large dams, but from run-of-the-river power plants for local use).

How should the Tasmanian story illuminate the Chilean case? To start with, the Patagonia Sin Represas campaign has powerful arguments on its side. Among them, firstly, that what looks like the cheapest option in the short and maybe medium term will be the most expensive in the long term. Secondly, that HidroAysén is not the only alternative available to solve the country’s purported ‘energy shortage’, because we have other options in abundance, like wind, geothermal energy and sun. Thirdly, that if HidroAysén benefits anybody, it is not the Patagonians. And fourthly, that a number of recent studies show that big, old-fashioned dams like the ones planned are not the clean energy that they claim to be (given increased sediment build-up, the fragmentation of the river ecosystem which results on the massive death of fish, etc.). Patagonia Sin Represas has used all this arguments effectively, and it has also appealed to our senses through powerful images, like those of the beautiful rivers Pascua and Baker, where the dams would be constructed; the huemules, our national emblems who are now an endangered species and many of whom live in the five thousand hectares to be flooded; and the dramatic effect that the transmission line would have on some of the most pristine landscapes in Chile and the world. Moreover, just as the No Dams campaign, Patagonia Sin Represas has progressively won the support of the general public, transforming itself from a narrow environmental movement into a social one. The best example of this is that, after the initial approbation of the dams by the government, on the 10th of May, 30 thousand Chileans gathered in Santiago to march against the decision. In every regional capital from north to south, this support was replicated.

How should the Tasmanian story illuminate the Chilean case? To start with, the Patagonia Sin Represas campaign has powerful arguments on its side. Among them, firstly, that what looks like the cheapest option in the short and maybe medium term will be the most expensive in the long term. Secondly, that HidroAysén is not the only alternative available to solve the country’s purported ‘energy shortage’, because we have other options in abundance, like wind, geothermal energy and sun. Thirdly, that if HidroAysén benefits anybody, it is not the Patagonians. And fourthly, that a number of recent studies show that big, old-fashioned dams like the ones planned are not the clean energy that they claim to be (given increased sediment build-up, the fragmentation of the river ecosystem which results on the massive death of fish, etc.). Patagonia Sin Represas has used all this arguments effectively, and it has also appealed to our senses through powerful images, like those of the beautiful rivers Pascua and Baker, where the dams would be constructed; the huemules, our national emblems who are now an endangered species and many of whom live in the five thousand hectares to be flooded; and the dramatic effect that the transmission line would have on some of the most pristine landscapes in Chile and the world. Moreover, just as the No Dams campaign, Patagonia Sin Represas has progressively won the support of the general public, transforming itself from a narrow environmental movement into a social one. The best example of this is that, after the initial approbation of the dams by the government, on the 10th of May, 30 thousand Chileans gathered in Santiago to march against the decision. In every regional capital from north to south, this support was replicated.

The battle so far has not been easy, though, and will not be. Whereas in the Tasmanian case the company which proposed the project had limited resources to promote it, HidroAysén, backed by the multinational Endesa, has spent millions of dollars lobbying for and publicizing its cause. An important part has been to infuse fear in the population, through threats such as that we are going to be left in the dark, or that the country will not be able to grow if the project is not carried out. Against this, the only option for Patagonia Sin Represas is to stand as a truly social and political movement with the legitimate support of the citizenry. Regarding this point, another important difference with the Tasmanian case is that, while in the latter the political parties swiftly took sides for or against the Franklin Dam, the main political parties in Chile have only made lukewarm declarations in support or against the project. Discounting a couple of independent senators and representatives, it looks as if our politicians are dragging behind the times, unable to take a stance on the national problems that really matter. In the background, members of the right-wing government have been explicit on their support to HidroAysén, and have had no quibbles to use their position of authority to put the message through. Moreover, no Green Party has been born to work for this and other pressing environmental and social causes (whoever the Greens are in Chile, so far, they have not managed to capitalize on the many voices of discontent).

image

HidroAysén has still a long way to go before its definitive approval, and it is in the meantime that those who oppose it have to come with concrete alternatives. Together with the No to the dams in Patagonia has to come a Yes to other paths not only of energy production but, more widely, of development and even property rights over common goods (under Pinochet´s dictatorship, the Chilean waters were privatized, and it was thanks to this law that Endesa could acquire a significant amount of the water rights, especially in the area of the project). What is at stake here is not only one of the most pristine landscapes in Chile, but in the planet. The conclusion should be obvious: One Patagonia is worth more than a thousand dams.

Author: Alejandra Mancilla, Chilean Journalist and PhD candidate in Philosophy, Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics (CAPPE), Australian National University, Canberra. www.alejandramancilla.wordpress.com

Please note the upcoming Symposium that SURCLA is organising: Indigenous Knowledges in Latin America and Australia | Locating Epistemologies, Difference and Dissent | December 8-10, 2011.

Please note the upcoming Symposium that SURCLA is organising: Indigenous Knowledges in Latin America and Australia | Locating Epistemologies, Difference and Dissent | December 8-10, 2011.